European Exploration and Native American Contact

It is difficult to make a reliable estimate of local Abenaki populations around 1600, when Europeans first ventured up the Kennebec into Merrymeeting Bay and then up the “Pejepscot”—a term then used to label the lowest section of the Androscoggin—but at least several hundred native people inhabited the Androscoggin watershed (out of some 100,000 in New England) at that time. Interrelated through marriage, and sharing a common dialect, these Indians had long participated in an annual cycle of migration that took them to seashore camps in the summer, to deep woods hunting camps in the winter, and back to their riverside villages for late fall feasting and spring fishing and planting. Known today as the “Amarascoggins,” this Abenaki group has long been erroneously identified by the term “Anasagunticooks,” a name associated with the missionary village of St. Francis (Odanak), near the St. Lawrence River in Canada’s Québec Province, and to those Indians—mainly Abenaki in ethnic origin—who resided there and traveled up and down the Androscoggin valley after 1700.

Throughout the 17th and during the first half of the 18th century, ongoing frontier warfare between French Canadian colonists in the St. Lawrence Valley and Protestant New Englanders moving north up Maine’s river systems placed the Androscoggin valley Abenaki in an awkward (and dangerous) position; forced to choose sides, many of these Indians retreated to mission villages in Canada where they stayed between seasonal hunting and fishing forays in their old territories to the south. Following the loss of Canada in 1763, English settlements spread further up the valley in relative security. Some of the Indians who had withdrawn to Canada, including the so-called “Anasagunticooks” (see above), returned to the Androscoggin valley where they interacted with the white settlers in a spirit of accommodation. Anxious to remain in their ancient homelands, these individuals were tested again during the American Revolution, when they found themselves split in allegiance between the colonists and the English. Even after that conflict, a number of Abenaki stayed in the region, assuming the role of guides, craftsmen or advisors to the white newcomers, and, in many instances, becoming absorbed into the white way of life through inter-marriage.

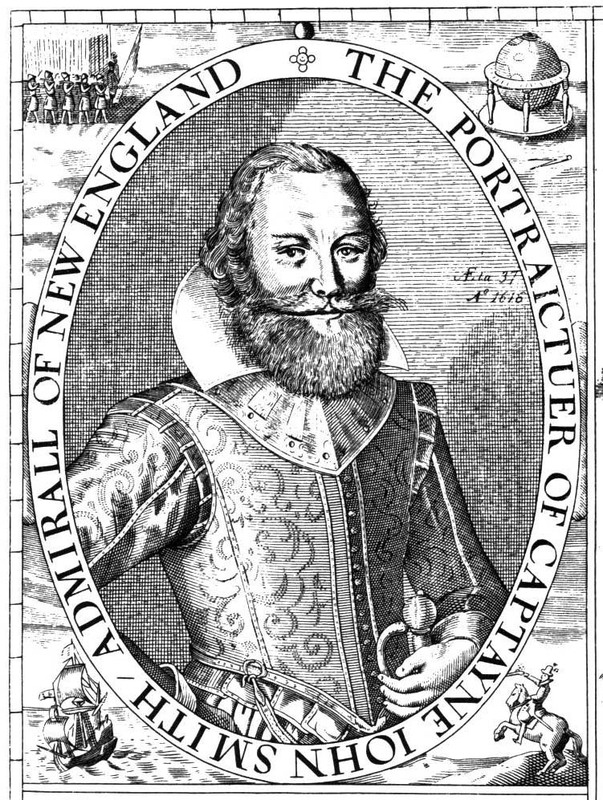

Among the earliest English explorers to venture up the Androscoggin was Captain Raleigh Gilbert. In September 1607 he and his men rowed longboats upriver from Brunswick, perhaps as far as Lisbon Falls. Upon encountering a group of Indians in canoes, Gilbert was recorded as having said, “Here we found nearly fifty able men, very strong and tall, such as their like before we had not seen. All were painted and armed with bows and arrows.” This image of another explorer, Captain John Smith, was originally published soon after he sailed into Merrymeeting Bay in 1614.

In 1628, Thomas Purchase became the first European to permanently reside on the Androscoggin when he was granted land at the present site of Brunswick. There, he built a fortified trading post and carried out an extensive trade with the Abenaki living in and near the river valley. In 1683, his descendant—also Thomas Purchase—sold a substantial amount of territory along the Androscoggin to Boston merchant Richard Wharton, another promoter of English settlements. Ratified by seven local Abenaki Sachems, this deed conveyed lands from the coast to the “uppermost falls in the said Andros Coggin River,” a phrasing that was to cause disputes over land titles for generations.

By the middle of the 17th century, the traditional Indian way of life along the Androscoggin was undergoing drastic change. An attitude of friendly curiosity turned to distrust and hostility—especially toward the English—as the native population sold off their lands (and, to their surprise, their hunting or fishing rights) for pots, rum, and cheap tools. Indian intertribal relationships also disintegrated due to the burgeoning fur trade and the introduction of firearms. The demand for furs, especially, strained the native economy by using up time previously spent in search of large game for food and skins; the fur trade also made natives aware of the importance of territorial boundaries, a concept foreign to the Abenaki before European notions of private land use and ownership were imposed on the region. The intermingling of cultures was further strained by the effects of the liquor trade, a significant component in English and French efforts to maintain Abenaki allegiances.

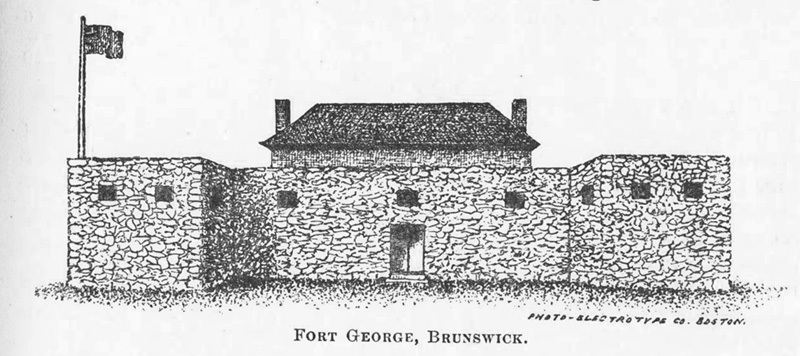

By 1673, the English had established a commercial fishing operation at Pejepscot Falls in Brunswick, catching some forty barrels of salmon and ninety kegs of sturgeon in just three weeks. To protect the lives and livelihoods of the settlers in that vicinity, Governor Andros erected the first fortification on the Androscoggin—“Fort Andross”—at Brunswick in 1688. It was from here that Colonel Benjamin Church and other Massachusetts soldiers set out upriver in 1690 to “visit the enemy, French and Indians at their headquarters at Ameras-cogen, Pejepscot or any other [place] . . . killing, destroying and utterly rooting out the enemy.” Church made it as far as the Indian stockade at Laurel Hill (Auburn), where, finding only a few old men and some women, he destroyed the camp along with its stores of grain and fish, and returned to the coast without accomplishing his goal. Fort Andross was replaced by the more substantially-built Fort George, shown here, in 1715.

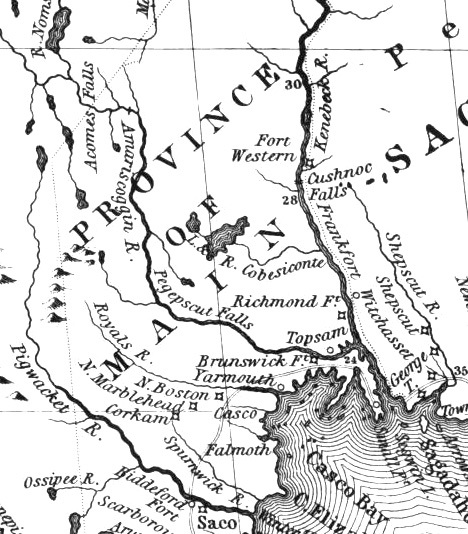

In 1714, a prominent group of Massachusetts men obtained a charter to the “Pejepscot Patent,” a huge tract of land on both sides of the lower Androscoggin River. From the relative safety of Boston, the Pejepscot Proprietors promoted the sale of land in and settlement of Brunswick, Topsham, North Yarmouth and other nearby towns. Upriver areas took longer to settle. (Detail from John Mitchell's 1755 Map of the British and French Dominions in North America)

From “Amascongan” to “Androscoggin”

The river now known as the Androscoggin, and from which the tribe inhabiting its shores received its names, was variously called the Anasagunticook, the Anconganunticook, Amasaquanteg, and Amascongan. The latter is the original of Androscoggin, as appears by the deposition of the Indian Perepole. The name has been written in some sixty different forms, as its sound was received by the ancient hunters, owners, and settlers. There seems to have been a disposition to make it conform to known words in the English usage. The name “Coggin” is a family appellation in New England; and it was easy to place before it, according to each man’s preference, other familiar names, and to call the stream “Ambrose Coggin,” “Amos Coggin,” “Andrews Coggin,” “Andros Coggin,” and “Andrus Coggin.” Vetromile says that Coggin means “coming”; and that Ammascoggin means “fish coming in the spring,” and that Androscoggin means “Andros coming,” referring to the visit of a former governor of the province. But the visit of Governor Andros was not made until 1688, while the river is called Androscoggin in an indenture, made in 1639, between Thomas Purchase and Governor Winthrop.

— Wheeler, History of Brunswick, Topsham, and Harpswell, Maine (1878)

A River of Many Names: Perepole’s Testimony

I Perepole of lawful age testify and say that the Indian Name of the River was Pejepscook from Quabecook what is now called Merrymeeting Bay up as far as amitgonpontook [New Auburn/Laurel Hill] what the English call Harrisses falls [“Great Falls” at Auburn/Lewiston] and all the River from Harrisses falls up was called ammoscongon and the largest falls on the river was above Rockamecook [Canton Point] about twelve miles, and them falls [Rumford Falls] have got three pitches, and there is no other falls on the River like them and the Indians yused to catch the most Salmon at the foot of them falls, and the . . . Indians yused to say when they went down the River from Rockamecook and when they got down over the falls by Harrises they say now come Pejepscook.

— 17th century deposition by Perepole, an Androscoggin valley Abenaki