Cleaning Up the River: Challenges, Opportunities and Achievements

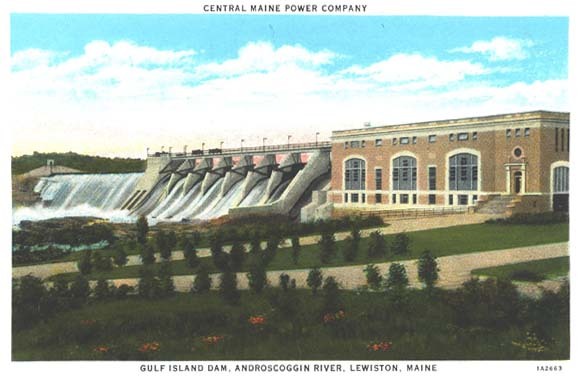

By 1940, many of the mills along the Androscoggin had recovered from the effects of the Depression and were actually increasing production in response to war-time needs. Not surprisingly, these same mills were discharging an extraordinary amount of toxic pollution into the river—as were all of the municipalities along its course. The construction in the late 1920s of the Gulf Island Dam several miles above the Great Falls at Lewiston/Auburn created “Gulf Island Pond,” which backed up the river nearly to Livermore Falls, and worsened the effects of the toxic wastes by drowning the rapids that had naturally provided oxygen to the water. Extremely low water in the river during the winter of 1940-41 brought these appalling conditions to a head, and Lewiston and Auburn residents made an official appeal to the Maine Sanitary Water Board for help. Soon afterward, the firm of Metcalf & Eddy, Engineers, of Boston, was hired to conduct a survey of the Androscoggin, and in February of 1942, they submitted a detailed report that included suggestions for remedial measures to clean up the river. One highly significant outcome of this investigation was the hiring, in 1947, of Dr. Walter Lawrance, Chair of the Chemistry Department at Bates College, as “River Master.” Under his direction, weekly discharge limits were set, and pressure was placed on the paper mills to find a substitute for the sulfite method of pulverizing wood. With the introduction of the kraft pulping process, the tide began to turn, and conditions on the river slowly started to improve.

Although great strides have been made in cleaning up the Androscoggin since the studies of the 1940s were carried out, the middle and lower sections of the river remain seriously impaired when judged against Maine’s other large rivers, including the Saco, Kennebec and Penobscot. As those who cast a line in the Androscoggin today understand only too well, the presence of dioxins and high mercury levels in fish inhabiting these waters is a reminder that more work remains to be done before this great waterway returns to anything resembling its pre-industrial condition.

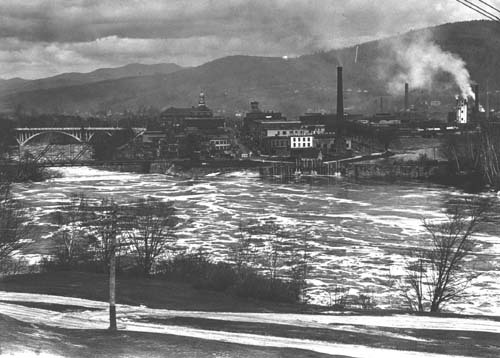

This 1934 view of Rumford was taken from “Falls Hill,” where Route 2 climbs to the top of the now-harnessed Great Falls. A good deal of the foam floating in the pool below the Falls was due to the dumping of tons of industrial and municipal wastes into the Androscoggin above Rumford.

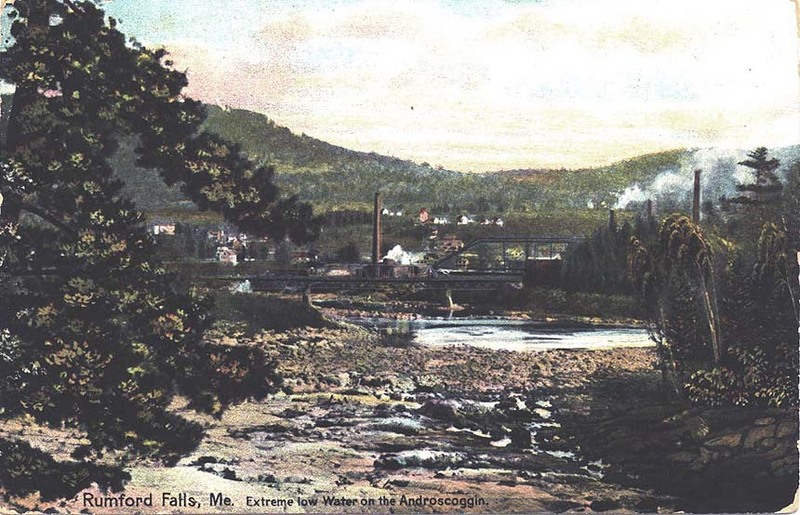

Before the introduction of treatment plants along the Androscoggin, low water levels turned this once proud waterway into a slow-moving sewer.

Over twenty dams, including this impressive structure at Lewiston, now exist on the Androscoggin. The view of those trying to clean up the river is that such dams have eliminated the aerating function of the falls on which they are located, hold back vast quantities of water already low in dissolved oxygen content, and allow the river water temperature to increase by exposing more of it to the summer sun.

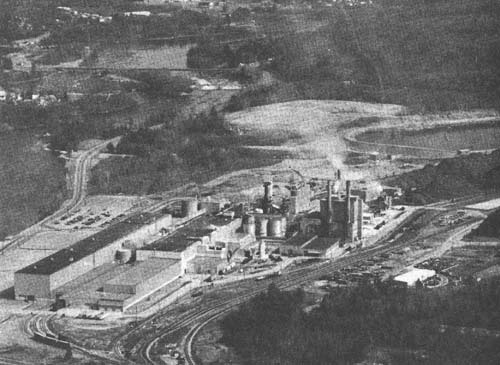

A thick layer of waste material coats the Androscoggin River in this aerial photo taken just below the Great Falls at Lewiston-Auburn around 1930. By the early 1960s, the Androscoggin had become one of the most severely polluted rivers in the United States. Dissolved oxygen levels from Berlin to Brunswick frequently reached zero during the summer, resulting in the death of virtually all fish and other aquatic life in the river.

The Turning Point

New Year’s Day, 1941, ushered in a year which not only would plunge the country into World War II, but would bring to a climax the terrible contamination of one of America’s loveliest rivers. The winter of ’41 began with an unusually scanty snowfall. . . . Snowfall was light and, in addition, there were no less than three winter thaws which took off the scarce snow unseasonably early. When spring came, by the calendar, there was no freshet, no great mass of water rushing down to the sea. The result was that the river was at the lowest level it had been for many a season. Now came the culminating factor: an unusually hot June and July, with little rain. From a faint whiff of hydrogen sulfite which rose from the river in May, the appalling stench of rotten eggs became progressively worse all up and down the river, and reached its climax in the most heavily populated section of Lewiston and Auburn, where roughly sixty thousand indignantly aroused citizens became vocally and politically vehement. It was a community disaster which was not only the topic of all conversation, but caused the slowdown of industry and business in general. Retail stores were deserted and some suffered physically from the effluvia. Jewelers, for example, nearly went berserk keeping their stocks of silverware saleable because the sulfite-laden air turned silver and other metals black overnight. If you were driving from Augusta to Lewiston, you began to smell it at North Monmouth, twenty miles from the city, and it increased in intensity as the road approached the river. Houses painted white turned black and blistered in great ugly patches, and by the time you had reached the city limits, you had to put up your car windows despite the heat and try not to breathe through your nose. It was revolting, and the exodus of families who could afford it became a locust-like invasion of the seashore and the mountain and lakeside camps—provided they were located far from the foul river. The wage earners must of necessity remain, and their outcries reached such a volume that the matter was brought before the newly created Maine Sanitary Water Board. Late in August, that body employed the same firm of Metcalf and Eddy of Boston [who had surveyed the Androscoggin in 1940 for Central Maine Power Company] to conduct a survey of the river and to recommend remedial measures. Thus, out of the despair and suffering of the populace was born the infant movement to recover the river.

— Page Helm Jones, Evolution of a Valley: The Androscoggin Story (1975)

The published findings of the 1941 survey carried out by Metcalf & Eddy included recommendations for the construction of sewage treatment plants in most of the larger communities on the Maine portion of the Androscoggin. A recently taken photo of the treatment plant here in Bethel appears below.

Growing public concern for controlling water pollution led to a 1977 amendment to the Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1972, commonly known as the “Clean Water Act.” Maine Senator (and later, Secretary of State) Edmund Muskie—a Rumford native—was a strong force behind this legislation, which established the basic structure for regulating discharges of pollutants into the waters of the United States and gave the EPA the authority to implement pollution control programs such as setting wastewater standards for industry. It also funded the construction of sewage treatment plants.

Opened in 1966, the former International Paper Company kraft mill at Jay was built at a cost of $54 million dollars. The operation’s primary treatment facility (part of which shows at upper right), installed in 1968-69, has been expanded over the years, as has the mill itself. A section of the Androscoggin River, including the falls at “Jay Bridge,” appears at left.