The Lonesome Trail

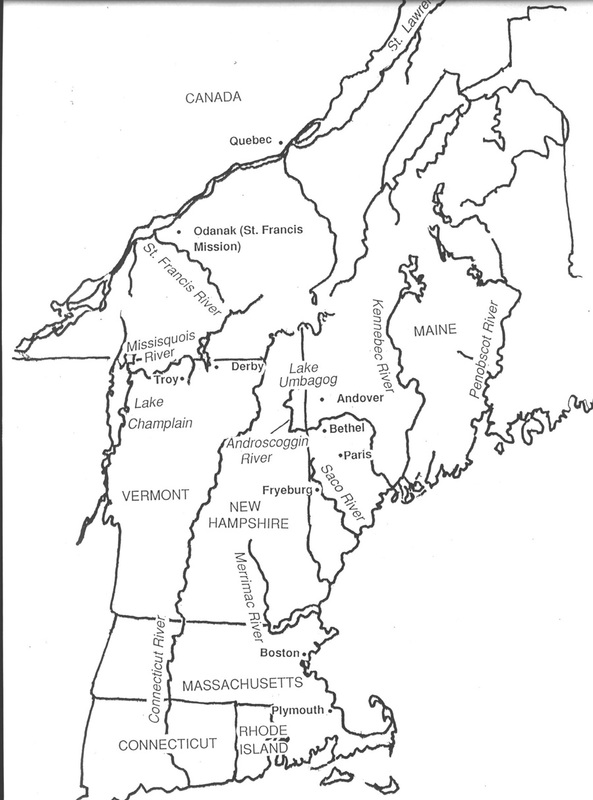

"After the close of the Revolutionary War . . . the old soldiers began to look eastward as a sort of promised land; large numbers came, and Sudbury Canada [Bethel] had its full quota." These remarks by one of Bethel's 19th century historians describe the beginnings of an era of general expansion in northern New England, and one which saw Maine's white population soar from 56,000 in 1783 to 300,000 in 1820—an increase of 450 percent. In the four decades between the time of the Last Indian Raid (1781) and Maine statehood (1820), many settlements in this region not only incorporated themselves as "towns," but also made significant strides in the areas of transportation, industry, education, religion, and local government. The development of compact villages, the establishment of post offices (Bethel's first post office opened at the Society's Mason House in 1815), and the proliferation of farms along the Androscoggin and other major waterways in the region gave visible testimony to this dramatic transformation. Surrounded by growing numbers of white settlers, some of whom earned part of their living by stripping the forests of their trees, many of the Abenaki remaining here after the Revolution surrendered their long and tenacious hold on their ancestral lands and departed for Canada or more remote parts of northern Maine and New Hampshire. For those few—including Molly Ockett—who remained, the dusty and wagon-clogged roads crisscrossing this territory were lonesome trails indeed.

According to an 1861 letter written by Silvanus Poor of Andover, Maine, to Dr. Nathaniel T. True of Bethel, Molly Ockett was living at the forks of the Ellis River in Andover with "old Phillip's (an Indian) family," when Ezekiel Merrill, that town's first settler, moved there with his family in May of 1789. According to Poor, "She was probably about 60 years at that time [and] was now too old for the chase, but spent much of her time about the lakes and ponds in this vicinity. She also used to bring in and dry moose meat that was killed by the other Indians in the spring of the year. . . . She spent about half of her time here when she was not trapping, and the remainder in Bethel and vicinity, making baskets, moccasins, wampam [sic], &c. She was industrious and peaceable, and was formerly quite handsome . . . and had a large supply of bracelets, jewelry, &c., but most of it was given away or disposed of before her death."

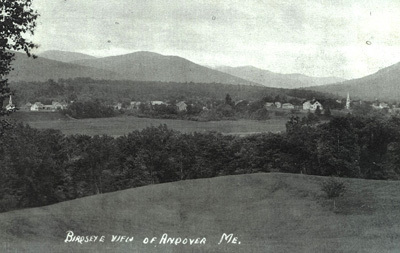

In July of 1790, Molly Ockett served as midwife at the delivery of Susan Merrill, the first white child born in Andover, Maine. The child's parents, Ezekiel and Sarah Merrill, settled in Andover in 1789 and constructed a small log shelter on the site of this massive Colonial Revival house, which still stands in 2007 and may contain elements from a dwelling built by the Merrills in 1791. Andover's first white family, the Merrills maintained frequent and close ties with the local Abenaki, including Molly Ockett. One local history mentions that "in the large hall of the new house, Indians were often permitted to lie stretched along the floor, wrapped in blankets, with their heads toward the brick fireplace."

A "Curious" Introduction: Vermont, 1799-1800

The following information from Samuel Sumner's 1860 History of Missisco Valley (Vermont) documents a time in Molly Ockett's life when she and other Abenaki were struggling to survive in the northern reaches of Vermont.

Several families moved into Troy and Potton in 1799, and in the winter of 1799 and 1800, a small party of Indians, of whom the chief man was Capt. Susup, joined the colonists, built their camps on the river, and wintered near them. These Indians were represented as being in a starving condition, which probably arose from the moose and deer being destroyed by the settlers. Their principal employment was making baskets, birch bark cups and pails, and other Indian trinkets. They left in the spring and never returned. They appeared to be the most numerous party and resided the longest time of any Indians who ever visited the valley since the commencement of the settlement.

One of these Indians, a woman named Molly Orcutt, exercised her skill in a more dignified profession, and her introduction to the whites was rather curious. Molly Orcutt was known as an Indian doctress, and then resided some miles off, over the Lake. She was sent for [to examine a white man's hand that was severely bruised in a "drunken frolic"], and came and built her camp near by, and undertook the case, and the hand was restored. Her medicine was an application of warm milk punch. Molly's fame as a doctress was not raised. The dysentery broke out that winter violently among children, and Molly's services were again solicited, and she again undertook the work of mercy, and again she succeeded. But in this case Molly maintained all the reserve and taciturnity of her race [and] retained the nature of her prescription to herself. She prepared the nostrum in her own camp, and brought it in a coffee pot to her patients, and refused to divulge the ingredients of her prescription to anyone; but chance and gratitude drove it from her.

In the March following, as Mr. Josiah Elkins and wife were returning from Peacham, they met Molly at Arnold's Mills in Derby; she was on her way across the wilderness to the Connecticut River, where she had a daughter married to a white man. Mr. Elkins inquired into her means prosecuting so long a journey through the forests and snows of winter, and found she was scantily supplied with provisions, having nothing but a little bread. With his wonted generosity, Mr. Elkins immediately cut a slice of pork of 5 or 6 pounds weight out of the barrel he was carrying home and gave it to her. My informant remarks she never saw a more grateful creature than Molly was on receiving this gift. "Now you have been so good to me," she exclaimed, "I will tell you how I cured the folks this winter of the dysentery," and told her receipt. It was nothing more or less than a decoction of the inner bark of the spruce.

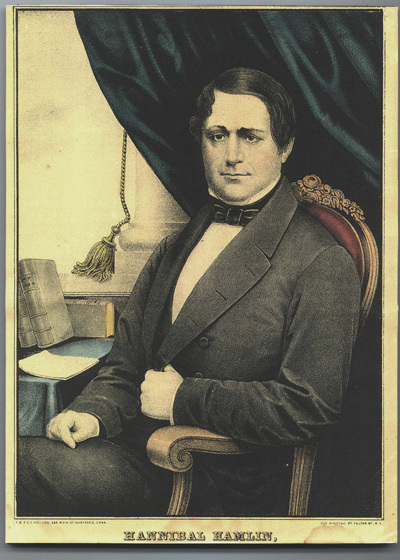

Molly Ockett Saves Hannibal Hamlin

The most famous story connected with Molly Ockett's healing powers has to do with her cure of the infant Hannibal Hamlin, who was born at Paris Hill, Maine, on August 27, 1809, and who later became Lincoln's first vice-president. During the winter of 1809-10, Molly Ockett was traveling through the town of Paris, some twenty miles south of Bethel, when, in foul weather, she sought shelter with the white residents at Snow's Falls. According to oral tradition, she was turned away, whereupon she uttered a curse on the place, said to be responsible for the lack of success of subsequent business enterprises in that neighborhood. Molly Ockett struggled along to the village of Paris Hill, where she was welcomed into the home of Dr. Cyrus Hamlin and his wife, Anna Livermore Hamlin. Returning later that spring, she found Mrs. Hamlin "sitting in her doorway one day, rocking her feeble infant." Molly Ockett "looked at the child very intently . . . and then said with great earnestness, 'You give papoose milk warm from cow, or he die.'" The infant, Hannibal Hamlin, "thrived with great rapidity" in response to this treatment, and Molly Ockett was thus able to repay the Hamlins for their earlier kindness.

During the last few years of her life, Molly Ockett was an occasional visitor to the Bethel home of Dr. Moses Mason and his wife, Agnes M. Straw. Their Federal style house, begun in 1813, is shown here in a circa 1905 photograph. The Mason House is now a museum facility operated by the Bethel Historical Society.