The Many Faces of Molly Ockett

Molly Ockett died in 1816, well before the invention of photography, but 19th century accounts describing her habits, activities, beliefs and physical characteristics reveal important clues to Molly Ockett's many "faces." Among the earliest of these descriptions (see below) is one published in 1807 that gives us a rare glimpse of Molly Ockett's life in the 1770s when she had a brief association with Henry Tufts, a shady character who traveled about traditional Abenaki territory for several years during that time. A later but equally valuable recounting of her life, based on the recollections of those who knew her, was authored by Dr. Nathaniel T. True and appeared in the August 5, 1859 issue of The Bethel Courier. True later expanded this account in a paper read before the Maine Historical Society and published in the Oxford Democrat newspaper in 1863. Summing up the life of this unique woman, he wrote, "That she possessed more than ordinary ability among those of her sex and people is evident. She gained the respect and even the love of whites at a time of life when the mere mention of an Indian was wont to kindle up in the breasts of white men anything but pleasing emotions."

Physical Appearance and Dress

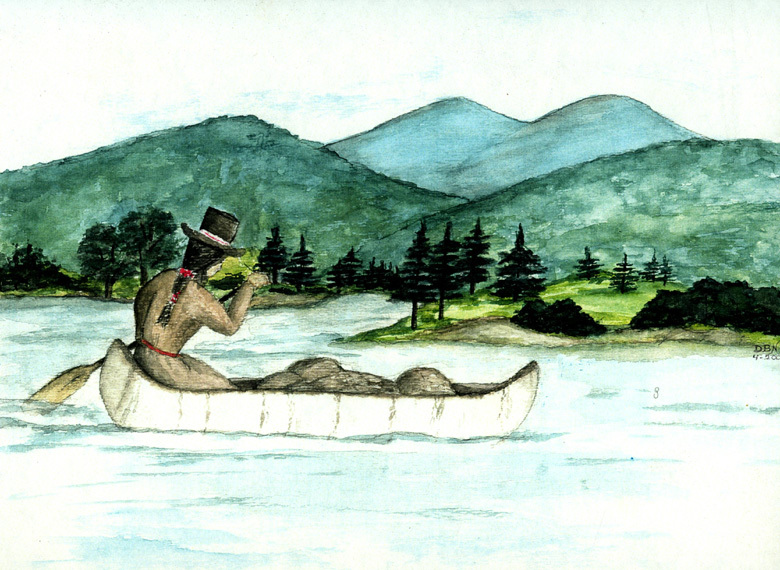

Molly Ockett was described by her contemporaries as an impressive woman, a woman possessed of "a large frame and features" and an erect carriage, even in old age. When allusion was made to this latter trait, Molly Ockett would remark, "We read, straight is the gate." She wore clothing typical of Abenaki women of her day: a knee-length European-style dress, leggings embroidered with dyed porcupine quills, beaded moccasins, and, during the colder months, a peaked cap decorated with colored beads. Aspects of her personality appear to have impressed white acquaintances as much as her physical presence. Ninety-year-old Martha Rowe of Gilead, Maine, in an interview with Dr. Nathaniel T. True in 1861, told of how she knew Molly Ockett as early as 1779, describing her as "a pretty, genteel squaw." Undoubtedly, Molly Ockett's "erect" posture made her stand out among other Abenaki of her day, but it was her proficiency with the English language, out-going personality, and expertise in the application of herbal remedies that won her the trust and affection of many white settlers. It would seem that this affection was returned by Molly Ockett in the generosity she showed to these newcomers and in her habit of greeting them upon returning from her travels with a kiss, first on one ear and then on the other.

Wife and Mother

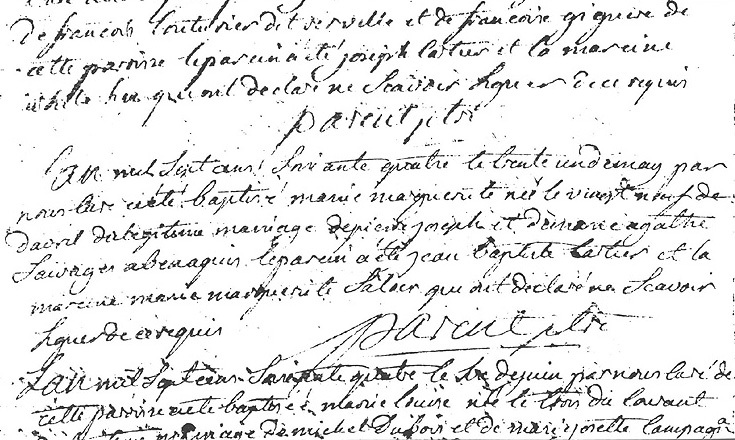

Molly Ockett's residence in Canada following Rogers' 1759 raid on Odanak may have been quite lengthy, as the baptism of her first living child, Marie Marguerite Joseph ("Molly Susup"), took place at the mission church at Odanak on May 31, 1764. The father of this child, Pierre Joseph ("Piol Susup") was apparently Molly Ockett's first husband, who died "some years before 1772." By 1766, Molly Ockett was in Fryeburg with a fellow Pigwacket named Jean Baptiste Sabattis. There is no record showing that Molly Ockett and Sabattis married, but they did have several children together, among whom were "Captain John Susup"; "Paseel" (Basil), who visited Bethel and was fairly well known to its early residents; a daughter who married a white man and lived near Derby, Vermont, in 1800; and a daughter who was the mother of Abbquasqua, a granddaughter of Molly Ockett who was twenty years old in 1789.

Molly Ockett's relationship with Sabattis, though lasting several years, was a stormy one and ended when his former wife came to Fryeburg to lay claim to him. The challenge was resolved "in a very Indian way" by a fight between the two women. The match occurred on Fish Street in Fryeburg, witnessed by the wife of a local settler and Sabattis, who sat on a woodpile smoking his pipe. Reports vary on whether Molly Ockett won or lost, but weary of Sabattis's "intemperate habits and quarrelsome disposition," she soon left to join Captain Swassin's group of Indians who frequented the area between Lake Memphremagog and Umbagog Lake (the latter very near Bethel). Molly Ockett's daughter, Molly Susup, later lived with her mother in Bethel, attending school and playing with the white children. She seems to have caused her mother some parental concern when she had a child, Molly Peol, by an Indian much older than herself—a match her mother staunchly opposed. Molly Susup later married a Penobscot Indian "who quarreled with her and left her." History records that Molly Ockett was "very much modified" by her daughter's conduct and felt that her own character, as well as that of her daughter, was destroyed.

Shown here is the 1764 baptismal record of Molly Ockett's daughter, Marie Marguerite. The original document resides in the Archives du Seminaire de Nicolet, near Québec City.

Moral Character and Religion

Molly Ockett's religious faith and moral character were much admired by her white friends, and were often commented upon in their recollections. For example, Silvanus Poor of Andover wrote, "When she was traveling and felt in a pious mood, she always walked straight and if she came to a puddle of water in the road she wouldn't turn out for it." The concept of strait, as in "narrow" or "confining," and straight, as in "upright," emerges often in stories connected to Molly Ockett. She was obviously fond of the Biblical passage, "strait is the gate, and narrow is the way, that leadeth to life eternal; and few there be that find it." Although she retained her Catholic ties, journeying back to St. Francis on occasion to make confession to the priest, Molly Ockett regularly attended Protestant services when in the Bethel area, and referred to Methodists as those "drefful clever folks." She did not feel bound by white religious conventions, however, and occasionally spoke at Methodist meetings, a right normally reserved for male members of the congregation. A well known story about Molly Ockett and the Sabbath was recorded by Dr. Nathaniel T. True in 1863:

She was easily offended. She made her appearance one Monday morning with a pailful of blueberries at the house of her friend, the wife of Rev. Eliphaz Chapman of Bethel. Mrs. C. on emptying the pail found them very fresh, and told her that she picked them on Sunday. "Certainly," said Molly. "But you did wrong," was the reproof. Mollyockett took offence and left abruptly, and did not make her appearance for several weeks, when, one day she came into the house at dinner time. Mrs. Chapman made arrangements for her at the table, but she refused to eat. "Choke me," said she, "I was right in picking the blueberries on Sunday, it was so pleasant, and I was so happy that the Great Spirit had provided them for me." At this answer, Mrs. Chapman felt more than half condemned for reproving her as she did. Who could possibly judge this child of nature by the same law that would condemn those more enlightened?

Another tale of Molly Ockett's church-going is connected with the town of Poland, Maine, where she was refused a seat at service. In a gesture that must have had a wonderful effect on the assembled congregation, Molly Ockett went outside, got a shingle bolt at a nearby mill and, carrying it inside the church, seated herself upon it directly in front of the pulpit, "where she attended every word during the service." Not surprisingly, Molly Ockett's religious reputation lingered with local residents long after her passing.

The photo at left shows a carved portrayal of St. Mary as an Abenaki woman. This sculpture, which stands at the front of the Abenaki church at Odanak, Québec, serves as a reminder of Molly Ockett's strong religious beliefs.

Generosity

Molly Ockett's generous nature is well documented by Henry Tufts, who met her in the 1770s. In his autobiography, published in 1807, Tufts records an instance of her generosity to a white man from Pigwacket (Fryeburg), who found himself without food for his family. The man journeyed to Bethel, as he "had used sometimes to visit the Indians for the benefit of hunting, trading, etc., by which means he had contracted some acquaintance with them and had heard that Molly Ockett always kept on hand a considerable quantity of money." Molly Ockett may have known the man from her recent residence in Fryeburg, as she loaned him twenty dollars, but "she rallied him on the score of his coming to borrow of the poor Indians, who (she said) were generally despised by the white people." She charged him to come the next winter and hunt furs to repay her, and this he did gladly, obtaining enough to repay her and have a surplus for his family.

Another tale of Molly Ockett's generosity which came to a less fruitful end concerns the seed corn that she brought from Canada to Colonel McMillan of Conway, New Hampshire, to assist him in improving his crop. On her way to his house, she stopped to visit Squire Richard Eastman and family, leaving the bag of corn by some logs between the house and a nearby mill run by Noah Eastman. While she visited the Squire, someone came along and carried the precious seed into the mill where it was ground into flour. This incident gave rise to a new version of the old "Lucy Lockett" nursery rhyme (sung to the tune of Yankee Doodle): Molly Ockett lost her pocket / Lydia Fisher found it / Lydia carried it to the mill / And Uncle Noah ground it.

Storyteller

Molly Ockett had a reputation, especially among the white settlers, as a talented storyteller. Because of her ability to relate stories of the past in great detail, her listeners became convinced that she was present during the events she described. For instance, Samuel Read Hall, an early resident of Rumford, Maine, believed Molly Ockett was born as early as 1685 based on her "recollection" of the Lovewell skirmish at Fryeburg in 1725. In truth, Molly Ockett was simply acting as an Indian "rememberer" or oral historian, transmitting past events she had heard from her elders and others around her. Molly Ockett also told her white friends other tales, some of which played into the settlers' superstitions and fears, and gained her a reputation as possessing destructive magical powers. She achieved this repute by punctuating her good works with occasional curses or warnings, some of which spawned legends that have been handed down through the generations. Three stories told by or about Molly Ockett, and featured in a booklet published by the Bethel Historical Society in 1991, are given below:

She maintained that when area Indians departed for Canada in 1755, at the start of the French and Indian War, they buried a quantity of gold in Paris, marking the spot by hanging two traps in a tree. This story took on added zest when, in 1860, a length of chain was found enmeshed in a tree on George Berry's farm in West Paris [near present-day "Trap Corner" on Route 26]. The treasure did not come to light at that time, which has allowed the legend to maintain its appeal for subsequent generations, especially school children in the area.

Another "buried treasure" tale associated with Molly Ockett is traditional in East Bethel families. . . . Molly Ockett had buried some of her possessions in a cache on Hemlock Island in the Androscoggin River off East Bethel. A settler stole them and when Molly later recognized her hatchet in his cabin, she placed a curse on the family which is said to have had an adverse effect on their prosperity from then on. A variation of this story identifies the buried treasure as gold, but the Hemlock Island locale is the same.

Stories told by Molly Ockett were not exclusively pleasant or historical, as she once predicted to people in West Poland [Maine] that the 18th of July would be so hot that water would boil in the wells and glass melt in the windows. This prophecy was told in a weird and vehement manner, disturbing those who heard it, and probably fostering the "witch" reputation Molly Ockett is reported to have had in Poland.

Sociability

One of Molly Ockett's outstanding traits was her ability to move easily in and out of the white communities. In her lifetime, she saw her native world devastated—her people killed, their land taken, and their resources depleted or destroyed—and yet she repeatedly showed kindness and sympathy toward individuals descended from the very people who had carried out these acts, making one wonder if she didn't carry a deeply-rooted, but suppressed, resentment against white folk in general. In any event, stories of gloom and doom seem relatively rare in connection with her life. More typical are recollections of her friendship with the settlers with whom she maintained close contact while on her travels. She often took her meals with them and repeatedly demonstrated a particular fondness for rum. Dr. Nathaniel T. True, writing in 1863, told of one occasion when Molly Ockett visited the Dr. Moses Mason House, now owned by the Bethel Historical Society:

When provided with a glass in any of the families which she visited, she would become very loquacious and entertain her company with stories and amusing anecdotes. . . . Her shrewdness was well shown on a visit at the Hon. Moses Mason's in Bethel. She asked for some rum. The Doctor knowing her weakness in this respect, poured out a half glass, being an allowance much smaller than usual, and told her this was all he had for her. "J-e-s-t enough," was her quick reply, as she devined the Doctor's motive.

Craftswoman

Molly Ockett was extremely adept in traditional Abenaki crafts, a fact much admired by the early white settlers of this region. Using techniques passed down through generations of her family, she created baskets, moccasins, leather-work, bark boxes, and pottery. She was especially skilled in beadwork, quillwork, weaving, and embroidery, as confirmed by a handful of surviving examples of her talents. A small birchbark box with cover, decorated with dyed porcupine quills (photo, left), was made by Molly Ockett for the family of Israel Kimball (1769-1829) of Middle Intervale (Bethel) and is now in the collection of the Bethel Historical Society; a larger box of similar design was given to the Maine Historical Society in 1860 by Mrs. John Kimball of Bethel. A pudding dish made by Molly Ockett for Mrs. Bragg of Andover was described as "a work of art [that was] white with a roll on top, resembling the finest whiteware." A duck feather bed made by Molly Ockett for Mrs. Swan of Bethel attests to her skill as a hunter and craftswoman. The Maine Historical Society also possesses a decorated folding pocketbook originally made for Eli Twitchell of Bethel. The hemp material for this purse (currently on display in the Maine State Museum's "12,000 Years in Maine" exhibit), which is covered with Indian-style embroidery using the long white hairs of a moose dyed red, green, blue and yellow, was prepared by Molly Ockett, though the actual purse, featuring a silver clasp dated 1778, was not constructed by her.

Indian "Doctress"

Molly Ockett's intimate understanding of the natural environment and her use of herbal remedies to cure many of the afflictions of both Indians and white settlers earned her the respect and gratitude of those around her. Henry Tufts called her "the great Indian doctress" and devised ways of getting Molly Ockett to reveal her secrets, a favor normally reserved only for those who were especially kind to her. But the question remains—why did the white settlers trust Molly Ockett to treat them during times of illness or accident? A decided lack of health-care options (Bethel's first physician, Dr. Timothy Carter, did not set up practice until 1799), a traditional reliance in rural New England on midwives for general medical care (in addition to delivering babies), and a lack of knowledge concerning local herbal remedies all worked to her advantage. By successfully turning raw materials (including Bloodroot, illustrated here) into tonics, salves, or poultices, Molly Ockett gained status in the world of the white settlers. Molly Ockett often came to Newry and Riley Plantation ("Ketchum"), where she taught Martha Russell Fifield to count in Indian, and shared with her some medicinal knowledge and instructions for making root beer and dyes. As a midwife, Molly Ockett attended the birth of Andover's first white child, born to her friend Sarah Merrill in July 1790. The Poland Spring mineral waters, world famous by the late 19th century, were said to have been esteemed by Molly Ockett, who was regarded by some of Poland's early residents as a witch, though skillful as a doctor. Perhaps the most re-told story of Molly Ockett's healing powers is her cure during the winter of 1809-10 of the infant Hannibal Hamlin, who later became Abraham Lincoln's first vice-president.