Background

In the centuries before Molly Ockett's birth around 1740, the Abenaki, an eastern Algonquian sub-group, maintained their historic homeland over an area stretching from the Iroquoian tribal lands in southern Québec to the northern Massachusetts border and from the Passamaquoddy territory in eastern Maine to the shore of Lake Champlain in western Vermont. Translated as "people of the Dawnland" or "eastern people," the Abenaki were composed of numerous bands of Native Americans historically identified by the names of the river valleys, or principal villages, in which they lived at the time of European contact. Molly Ockett was a member of the Pigwackets, who occupied the Saco River Valley and environs, and whose main village was situated on a plateau above the Saco intervales at present-day Fryeburg, Maine—some forty miles south of Bethel and a short distance east of the present border between Maine and New Hampshire. Among those Indians with whom the Pigwackets would have had close communication were the Pennacooks of the upper Merrimack and Pemigewasset River valleys, the Sokokis and Coosaukes of the upper Connecticut and Ammonoosuc watersheds, and the Amarascoggins, who resided in the Androscoggin River valley.

Data is lacking for a reliable estimate of Abenaki populations before 1600, but it is reasonable to state that in that year several thousand individuals inhabited the White Mountain region of Maine and New Hampshire, with a total population in New England as a whole of well over 100,000 native people. Interrelated through marriage, and sharing a common dialect, the Abenaki participated in an annual cycle of migration that took them southward to seashore camps for the summer, northward to deep woods hunting camps in the winter, and back to their riverside villages for late fall feasting and spring fishing and planting.

By the middle of the 17th century, the traditional Indian way of life in this region was undergoing drastic change. An attitude of friendly curiosity turned to distrust and hostility as the native population watched their numbers rapidly dwindle due to virulent epidemics introduced by Europeans. Indian intertribal relationships disintegrated due to the burgeoning fur trade and the introduction of firearms. The demand for furs, especially, strained the native economy by using up time previously spent in search of large game for food and skins; the fur trade also made natives much more aware of the importance of territorial boundaries, a concept foreign to the Abenaki before European notions of private land use and ownership were imposed on the region. The intermingling of cultures was further strained by the effects of the liquor trade, a significant component in English and French efforts to maintain Abenaki allegiances as the century wore on.

Molly Ockett entered the world in a period when her people faced ongoing and violent frontier warfare from a succession of colonial conflicts between French Canadian colonists in the St. Lawrence Valley and Protestant New Englanders on the Atlantic seaboard. Caught in the middle, the Abenaki were forced to choose sides, with many retreating to Indian mission villages in Canada where they stayed between long, seasonal hunting and fishing forays in their old territories to the south. Following the loss of Canada by the French in 1763, English settlements spread northward into interior Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont, in relative security. Some of the Indians who had withdrawn to Canada, including a number residing at the Québec missionary village of Odanak on the St. Francis River, returned to the Saco and Androscoggin valleys where they interacted with the white settlers in a spirit of accommodation. Anxious to remain in their ancient homelands, these individuals were tested again during the American Revolution, when they found themselves split in allegiance between the colonists and the English. Following that conflict, a small number of Abenaki stayed in the vicinity, becoming absorbed into the white way of life through inter-marriage or by assuming the role of guides, craftsmen, or, as in Molly Ockett's case, medical practitioners and advisors to the white newcomers.

King Philip's War (1675-1676), a brief but bloody conflict between Native Americans and English colonists in southern New England, marked a turning point in 17th century encounters between Indians and Europeans. However, it was not the worst disaster to occur during a long period of tension and upheaval. That honor goes to the "Great Dying," a cataclysmic scourge brought upon the native population by epidemics—notably smallpox, measles, and typhus—from which they had no immunity. Spreading into this region from the mouth of the Saco River in 1617 and up the Connecticut River by 1635, these contagious diseases seriously reduced Abenaki numbers, perhaps by as much as 90 percent.

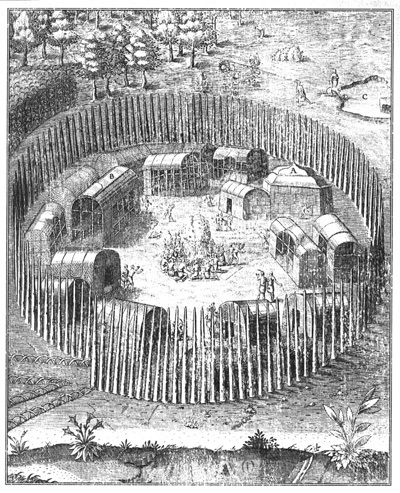

A major focal point of Molly Ockett's world was Pigwacket, the ancient Indian enclave at present-day Fryeburg, Maine. This late 16th century representation of an East Coast Algonquian village conveys something of Pigwacket's appearance in the decades before Molly Ockett's birth. A description of the semi-abandoned Pigwacket village made in 1703 by an English scouting party led by Major Winthrop Hilton states: "When we came to the fort, we found about an acre of ground, taken in with timber [palisaded], set in the ground in a circular form with ports [gates], and about one hundred wigwams therein; but had been deserted about six weekes, as we judged by the opening of their barnes [storage pits] where their corn was lodged." The bark-covered wigwams or longhouses in this view (excepting "A") are typical of Abenaki dwellings used in this region. By tradition, "Pigwacket" is said to mean "at the cleared place."

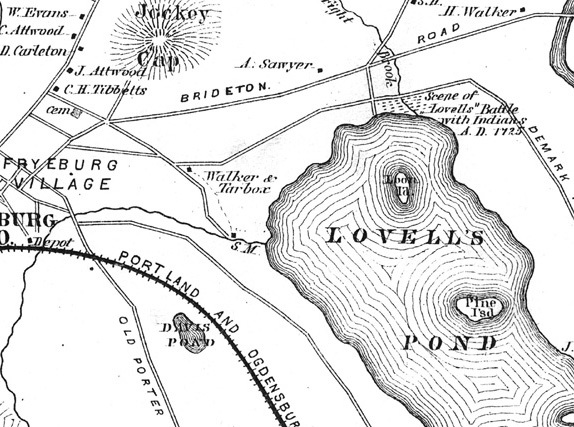

The village of Pigwacket was the scene of one of the most widely known military events in colonial New England history when, on May 8, 1725, thirty-four English scalp hunters led by the daring Captain John Lovewell engaged some forty Abenaki led by the Pigwacket chief Paugus. The ensuing "Battle" resulted in heavy casualties on both sides, including Lovewell and nineteen of his compatriots, as well as Paugus and an equal number of his followers. A major result of this legendary skirmish was a general shift in the remaining Abenaki population in this region to the north and east, away from entanglements of the English-French rivalry.

A monument commemorating the "Battle of Lovewell's Pond" was erected at Fryeburg in 1904 by the Society of Colonial Wars. The monument's plaque states, "To mark the field of Lovewell's Fight on the 8th day of May 1725 between a company of Massachusetts Rangers of 34 men and 80 warriors of the Pequawket tribe led by Paugus in a contest lasting from early morning until after sunset / The Indians were repulsed and their chief killed." No mention is made on the monument of the many centuries the Abenaki had peacefully occupied this place before it was "discovered" by Europeans.