Dispossession and Accommodation

The permanent colonial settlement of the "eastern slope" of the White Mountain region—the heart of Molly Ockett's world—began in the early 1760s at Fryeburg and followed an arrangement common to much of northern New England in the years just before and during the American Revolution. Unlike in earlier days, when provincial governments granted townships to settlers who also acted as "proprietors" (owning home lots clustered in villages and holding pasture land and woodlots in common with other shareholders), many of the earliest towns in this vicinity were granted to people of influence who had little, if any, interest in relocating to the North Country. These absentee landlords, some of whom received grants as payment for military service during the French and Indian wars, hired surveyors to create town plans divided into grid patterns of roughly 50-acre parcels that did not call for a centralized village and which virtually ignored the local topography.

During the 1760s, a handful of white settlers, anxious to take advantage of the agricultural, forest, and mineral wealth of this newly-opened territory, purchased farmsteads from these town proprietors or, in some cases, were given land in an effort to meet certain grant stipulations. "Gateway" towns like Fryeburg, Maine, and Conway, New Hampshire, were hurriedly established, and within a few years the pace of land granting quickened, so that before the outbreak of the American Revolution, most of the towns in this area had been laid out and mapped, though some had yet to see land cleared for farmsteads. The emigration of people into this region from the south was slowed but not halted by the Revolution. Far removed from the panic and confusion in New England's older communities, these emerging backwoods settlements were relatively safe from British reprisals.

Numerous stories handed down by descendants of the first white settlers tell of how their most frequent visitors during the coldest months were the Abenaki, some coming from St. Francis and all of whom were struggling to retain a measure of their traditional culture, despite being dominated by an ever-growing English population. Camping seasonally in bark wigwams near Fryeburg and other frontier settlements, these native people, including Molly Ockett, survived by hunting, fishing, and trading furs and homemade crafts and cures to the white residents. Part of a small ethnic minority numbering only in the hundreds, Molly Ockett made use of her special skills and vast medicinal knowledge to forge important and useful relationships with these newcomers—links that served her well throughout the remainder of her life.

Molly Ockett and others of her kin-group were in the Bethel area in the mid-1760s and witnessed the clearing of land and the construction of houses as white people arrived to usurp the former Abenaki territory. The civilizing tendencies of these pioneers are well conveyed in this early 19th century depiction of Oxford County's "shire town" at Paris Hill village, some twenty miles south of Bethel.

View of Paris Hill, 1802. Oil on pine board, 30" x 48", artist unknown. An over-mantel painting from the Lazarus Hathaway House, Paris Hill. Gift of Miss Mabel Hathaway to Hamlin Memorial Library, 1957. Courtesy of Hamlin Memorial Library.

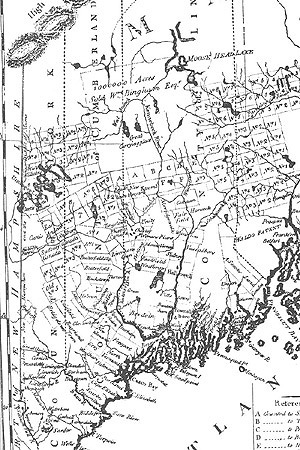

Abenaki survival in post-Revolutionary Maine (delineated here in a 1795 map by Osgood Carleton), as well as other parts of northern New England, depended on accommodation to the white man's world. Often camping near the newly laid out communities for months at a time, Indians continued to visit and travel throughout the region well into the 19th century. Bethel historian Dr. Nathaniel T. True, writing in 1859, stated, "It was no uncommon sight for quite a fleet of boats [canoes] to pass up and down the river in company." Sudbury Canada, now Bethel, appears just to the right of the "m" in "New Hampshire."

The first white settlers to venture into this region discovered something the Abenaki had known for generations: the level "intervales" alongside the Androscoggin and other rivers contained amazingly fertile soils that were ideal for raising a variety of crops, most especially corn. Indian "cellars" for storing corn and other provisions were found near Bethel's Riverside Cemetery when the "Mayville" section of the town was opened up to farming in the 1770s.

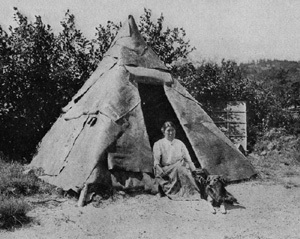

Despite her familiarity with the ways of the white settlers, Molly Ockett practiced an Indian style of living during her travels throughout the area, including trips to northern Vermont, New Hampshire, and Canada. Stopping at favorite campsites and sharing meals at the home of special friends, Molly Ockett preferred to dwell in bark-covered wigwams made of tall saplings enclosing a space about 15 feet in diameter.