War Reminiscences of the Bethel Company, Company I, Fifth Maine Regiment [Number 19]

Title

Note

Identifier

Text Record

Subjects

Collection

Full Text

WAR REMINISCENCES

OF THE BETHEL COMPANY,

Company I, Fifth Maine Regiment.

[By Col. Clark S. Edwards]

No. 19

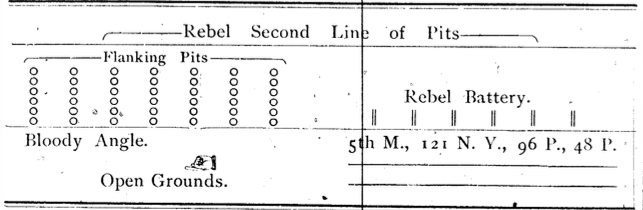

At the close of our last number we were in the rifle-pits that we had captured at such terrible loss on that tenth of May 1864, at Spotsylvania, where we suffered as much, if not more, than any other regiment in proportion to our numbers. The reason for this fearful loss of men was this; The Fifth Maine was on the front and left of the first line of battle. Between us and the enemy was an open field of fourteen or fifteen rods in width, reaching nearly to the Bloody Angle. There was a gradual rise of fifty or sixty feet. As we charged across this field, the rebels from their protected and fortified position had a great advantage over us as will be seen from the illustration, showing the relative position of the Fifth Maine and the enemy.

The first line of pits occupied by the rebels was the flanking pits. In our immediate front was a rebel battery of six guns. The battery and infantry in front, aided by the “flankers” poured a deadly fire upon us and our loss was consequently very great. On the 11th of May we lay in camp till near noon, having made a report of our loss on the previous day as follows: Twenty-seven or eight killed or mortally wounded, fifty-two severely and slightly wounded, and twenty-one missing in action.

On the evening of the 11th it began to rain. We had moved fifty or seventy-five rods to our left and had been in camp but a short time when we were ordered into line and were held in that position for nearly two hours; the rain poured down in torrents; the boys were about worn out with fatigue and loss of sleep, and many fell asleep even while in line; as for myself, I had not had a night’s rest since leaving our winter quarters on the Hazel.

On Thursday morning at the first gleam of light we were in line ready for action. The battle soon began on our left, Hancock making his grand charge and capturing nearly four thousand prisoners and twenty cannon. The rebels were forced back to their second line where they held their position for some time in a hand-to-hand contest. At this time Gen. Lee was hastening Wilcox’s division of Early’s Corps forward to fill the gap made by the loss of Johnson and a large part of his division. The tide of battle would soon have been turned and probably in favor of Lee, had not the Sixth Corps under General Wright been ordered to advance upon the enemy. The Fifth Maine Regiment was in the Second Brigade of the First Division of the Sixth Corps, and was the first regiment to reach the works that Hancock had captured. I was ordered by General Upton to charge on a Confederate force a little to the right of the Bloody Angle. The charge was made and about one hundred prisoners were captured from the first pit. Then the rebels in the second line threw up their handkerchiefs, white rags, pits of paper, indicating a desire (?) to surrender. They shouted to us of the Fifth Maine to charge on them, saying that they would surrender, but not having implicit confidence in what they said and knowing that they were strongly entrenched, I did not deem it wise to lead my men to slaughter. Had we charged upon them we would have been obliged to cross the first line of pits and at least fifteen rods of open ground before we could have reached them; this would have given them the opportunity, doubtless desired, of wiping out what remained of my little regiment. I urged them to come into our lines but their reply was, “If we do without your charging on us, those in our rear will report us as deserters and we will be shot if exchanged.” As we fell back they gave us a few parting shots, wounding two of our regiment.

We formed our lines in a slight ravine with a small ridge between us and the enemy. The battle had now begun in earnest. As I look back in memory, 35 years ago today, I see the battle as it raged, with the air filled with solid shot and shell. Thousands of brave men fell that day, that our country might remain one and inseparable. Just in the rear of our line were two guns which had been abandoned by Hancock an hour or two earlier in the day; the guns belonged to the United States, Battery C. The caissons and limbers were near. We run the guns up so that their muzzles rested on the works we had captured.

Lieut. Joseph White of Company E, and myself ran up the first gun; (he has received a pension for thirty years, for injuries received in his left shoulder at the time), while the second gun was moved by Captain Lamont and some others. Having found two or three gunners of the Battery, I at once set them to work; ammunition was brought from the caissons and firing immediately began. I ordered the fuse to be cut shot so as to have the shells explode over the second line of rebel pits if possible, for I wanted to square accounts with the fellows who had endeavored to trap us and who wounded two of our men as we fell back. At this time the battle had become general along the line left of the Angle. The old regiment of the Sixth Corps was put in behind the slight ridge above mentioned, to hold the position that had been captured by Hancock in the early morning. It was now nine o’clock A.M., and the heavens were weeping in torrents. The infantry was engaged in one of the most fearful conflicts of the war. Twelve or fifteen regiments were loading and firing at will for hours. Many of our boys burned four hundred rounds of ammunition that day.

It was in our front that the famous oak tree, sixteen inches in diameter was cut off by the minie balls alone. The awful musketry was kept up until two o’clock Friday morning, May 13, when the rebels fell back, swinging their line around to the right in order to cover Spotsylvania Court House and to shorten their lines, for Hancock had made a long gap in their ranks by the capture of many prisoners and the killing and wounding of thousands of men. The reason for the constant firing for eighteen hours was: Grant had broken the center of Lee’s line to recover his lost position; Lee was massing his best troops in two lines of battle some twelve hundred yards in the rear, preparing for an advance movement and the recapture of the works that had been lost, but no army no matter who the leaders may have been, could face successfully the terrible storm of leaden hail that poured many hours without cessation into their ranks. The Fifth Maine Regiment was in the thickest of the fight from half-past six A.M., till half-past seven P.M. We were relieved by some of Burnside’s troops and moved back and bivouacked for the night; the firing ceased about half-past two on the morning of the 13th.

Just after daybreak, Chaplain Adams and myself rode back to the spot we had left only a few hours before where the regiments that relieved us were in line. As we sat there on our horses, noticing the trees that had been cut down by bullets I said to the Chaplain: “If Barnum had that stump in his museum in New York, he could make a fortune by exhibiting it.” About three years after the close of the war, the trunk of the tree was sent to the National Museum in Washington, where it can now be seen.

Before Chaplain Adams and myself returned to our regiment we witnessed scenes that were heart rendering in the extreme. We had seen the dead and the dying on many fields; heard the groans and pitying cries of the wounded as they lay freezing between the lines at Fredericksburg that cold December night in ’62; had seen suffering that no words of mine can describe such as the cremation of bodies in the brushwood on the Peninsular and in the Wilderness; but the awful scenes that we witnessed at this point, were more terrible than any other we saw throughout the war. The Ambulance train was removing the dead and wounded from the pits where they lay from three to five deep; a badly wounded man with two or three dead men upon him was not an exceptional case; in some parts of the pits the water was ten or fifteen inches in depth, highly colored with blood; a heavy rain had fallen, and in this water the bodies of many confederate soldiers were found. On our own side of the pit the ground was strewn with the dead.

It was here that Captain Lamont of the Lewiston Company fell, pierced by more than twenty bullets. So mangled was his body that the burying party was obliged to roll his remains in an army blanket before they could be taken to the grave.

Of the Bethel Company D. A. Edwards, John E. Bean, and Levi Shedd were severely wounded, while the killed were the noble Martin of Rumford, and Andrews of Andover. The battle of Spotsylvania was one of the severest of the war, and the position occupied by the Fifth Maine was one of honor as well as of great responsibility.

sketches.

At Spotsylvania, May 12, 1864, Jerry W. Martin, that brave and noble soldier from Rumford, was killed. Jerry, as the boys called him, was a favorite with all his comrades. He was always ready for action, never shirking the performance of duty. For several days prior to the day of his death he had been troubled by a fearful felon on his right hand. On account of this disability, Surgeon Warren had given him a written excuse that released him from all obligation in actively participating in the battles of the Wilderness, but no excuse was wanted. Wherever there was fighting to be done, Martin was sure to be found. I well remember him coming to me on the morning of May 12, saying “Colonel, I want to go with the boys today.” Knowing that he had good reason for remaining in the rear, if he so desired, I advised him to keep out of danger telling him that he had been excused from duty this day by our surgeon. The brave fellow, however, begged so earnestly to be allowed to go into battle, I consented. He had in his cartridge-box sixty rounds of ammunition. After the charge had been made and hundreds of prisoners captured, our position was one that demanded constant loading and firing. The “historic” oak tree that was cut down by minie balls was directly in our front. Martin soon used his sixty rounds of ammunition and came to me for more. I remember using my sword as a screwdriver in opening a box of ammunition for him. When I had filled his cartridge-box I told him as he left me not to expose himself but he had no fear of the rebel bullet. I did not see him again. He fell a hero, bravely fighting. No better soldier ever enlisted in the Bethel Company than Jerry W. Martin. At one time I offered him an appointment as Corporal or Sergeant, but he preferred to remain a private.

A few years ago when visiting the battlefield around Fredericksburg, I spent some time in the national cemetery on Mary’s Heights looking through the Maine section for the marble slabs indicating the last resting place of Martin, but I did not succeed in locating it. I have no doubt but his grave is in that cemetery and numbered among the seven thousand that are marked with that sad, sad word, “Unknown.”

David E. Andrews, son of the late Russell Andrews was born in Andover, Maine in 1841, enlisted in the Bethel Co., May 1861 and was mortally wounded May 12, 1864 at Spotsylvania, in front of “Bloody Angle” and died in the hospital at the White House on Pamunkey River, June 2. We cannot say too much in praise of this gallant soldier. He always was ready to meet all the hardships, of war, never complained, let the task be ever so hard. I can now seem to see him on the march across the Peninsular; there the army was commanded by “Little Mac” when it was fighting by day and retreating by night, what is known in history as “the seven days’ fight.” Then again I see him on the move from our camp near New Baltimore to Belle Plain in that fearful storm of snow and rain. On reaching there, we found neither fire nor wood, and the ground covered fully ten inches deep with snow and water with the cold north wind blowing across the broad Potomac—Yes, and no one heard a murmur from his lips; again I see him on that memorable march from Fairfield Court House to Manchester Md., on hundred and twenty-seven miles in five days! And after one day’s rest, a march of thirty-seven miles to the Gettysburg battlefield in eighteen hours. Again we remember him at Rappahannock Station as he was taking care of the wounded and feeding the hungry rebels until his last hardtack was gone. I think he was in all the battles in which the Fifth Maine Regiment was engaged from Bull Run, July 21st., 1861 to May 12, 1864, in which he did his last fighting. Martin fell beside him a few minutes before he received the fatal shot; the two were always together; tent mates in camp, and intimately acquainted when boys before the war, living quite near together, in adjoining towns. They are now members of that great band of which it is said there is no separation. Andover may well be proud of giving for our country one of its noblest sons.