Western Maine Saints [Part 3]: A Bethel Family (Frost)

Title

Source

Publisher

Date

Format

Series

Identifier

SERIAL 1.30.4.6

SERIAL 1.31.1.3

SERIAL 1.31.2.4

SERIAL 1.31.3.3

Text Record

People

Collection

Full Text

Western Maine Saints [Part 3]:

A Bethel Family (Frost)

by Jayne W. Fife, with Roselyn Kirk

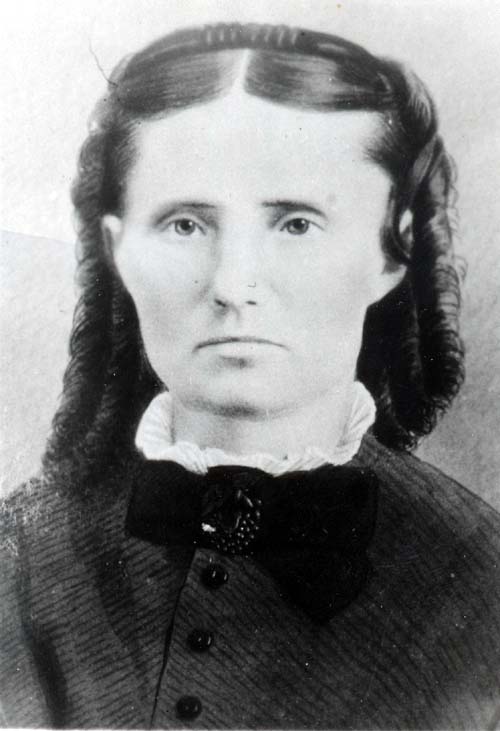

Mary Ann Frost Stearns Pratt. Photo courtesy of Jayne Fife

Mary Ann Frost Stearns was a small determined woman, a widow with one child, when she married LDS Apostle Parley Parker Pratt, a widower, in Kirtland, Ohio, in 1837. That decision resulted in her bearing their first child, Nathan, in a one-room log cabin near Far West, Missouri, and being abandoned when Parley was arrested, charged with murder and sentenced to death. When reprieved, he was held in the Richmond and Columbia, Missouri, jails for eight months. During that period, Mary Ann spent time with him in jail from the beginning of December 1838 to March 17, 1839. There she cared for Parley and her two children. When she left, she carried Parley's writings out in her clothing, thereby risking her life so they could be published.

With Parley still in jail, she was forced to leave Far West on penalty of death. Having no means of transportation, a kind Church member took her to Quincy, Illinois. When they reached a swollen creek that ran parallel to the Mississippi River, she got out of the carriage to lighten the load. Crossing the narrow bridge, she looked back to see her daughter, Mary Ann's, bonnet bobbing in the water. By a miracle, the child's life was saved. Later, as one of the last to leave Nauvoo, Illinois, as the Saints were once again driven from their homes, farms and sacred temple, she endured abandoning the graves of two small children, Nathan and Susan. Parley had already reached Council Bluffs, Iowa, with the main body of the Saints, including his now six other wives and several infant children.

Making the decision to leave Parley and relying on her own resources to support her own children, she remained true to the promises she made in the spring of 1835 when she joined the Church of Latter-day Saints in western Maine. She wrote, "I was baptized into the Church of Jesus Christ, being converted to the truthfulness of its doctrines by the first sermon I heard. And I said in my heart if there are only three who had to endure, I have everfelt the same, my heart has never swerved from that resolve."

Mary Ann was born in Groton, Caledonia County, Vermont, to Aaron and Susan Gray (Bennett) Frost on 14 January 1809. Her brother, Orange Clark, and sister, Naomi, were also born in Groton, respectively, on 23 February 1813 and 25 January 1814. Aaron and Susan's first child, Lidania, was born on 10 October 1802 at Berwick, Maine, where Aaron's parents lived. The next three children, Aaron (10 March 1804 - 15 October 1804), David Milton (b. 28 July 1805) and Lucretia Bucknam (b. 24 November 1806) were born in North Yarmouth, Maine, where Susan's parents lived. The last four children were born in Bethel: Olive Gray on 24 July 1816, Sophronia Gray on 3 October 1818, Nehemiah on 4 March 1821, and Huldah Alvina in 1825.

Aaron was a descendant of George Frost, originally from Binstead, Hampshire, England, who came to Winter Harbor/Biddeford Pool near the mouth of the Saco River between 1623 and 1629. George's son, John, was killed during the early stages of the Indian Wars and his other son, William, who owned land in Saco, fled with his family to Salem, Massachusetts, where he lived until 1679, when he purchased land in Wells and returned. On 7 May 1690, William and his brother-in-law, James Littlefield, were killed by Indians, who carried away William's son, Nathaniel.

Three succeeding generations of George Frost's family lived in Berwick, Maine, including great, great, great grandsons, Moses and Eliot, who served in the Revolutionary War. After the War, six of Moses' children moved to Sudbury Canada (later known as Bethel): Moses, Thomas, Dominicus, Nathaniel, Lydia, and, eventually, Aaron.

Mary Ann often told her children about her early life. One story they loved to hear was called, "Needles and Pins." When she was a child, she had to walk a mile and a half every day to an Androscoggin River crossing where workmen waited to row a group of children across the river to a little schoolhouse. After school, the children waited until the men returned from work to row them back. While waiting, they often played in the boat. Sometimes, they let it out into the river as far as the rope would allow and then pulled it back to shore. Once, when it struck the shore very hard, Mary Ann was knocked into the deep water. The other children ran screaming for the workmen. When they arrived, Mary Ann, who had struggled valiantly until overcome, was rescued and quickly rolled in the grass as water drained out of her ears, nose and mouth. She was carried to a nearby house, wrapped in a warm blanket and put to bed. When she finally opened her eyes, she said, "Oh, I feel so funny, just like needles and pins poking all over me."

As Mary Ann grew older, she became an expert in spinning, dyeing and weaving fabric, and knitting and sewing clothing. When she was twenty three, she married Nathan Stearns, son of Charles and Thankful Bartlett Stearns. A descendant wrote that Mary Ann "fell in love with young Nathan Stearns who courted her for four years, beating a path through the woods to come every Sunday to see her. She had knitted enough socks to last a lifetime by the time they were married," which was on 1 April 1832, Nathan's twenty-third birthday.

The Charles Stearns homestead in the Mayville section of Bethel.

The buildings were owned by Henry Enman when they were destroyed by fire on 6 June 1936

In an autobiography written by Nathan and Mary Ann's only child, in 1896, she related, "My father, a well-beloved son, was the chosen one to inherit the paternal homestead and to nurture and comfort the declining years of his aged parents." Accordingly, the newlyweds settled into the Mayville home and farm [above] where Charles and Thankful Stearns had raised their nine children, and that is where their only child was born on 6 April 1833. Continuing her remembrances, daughter Mary Ann wrote, "My father and mother were lovers in the true sense of the meaning and she often said that she never received a cross word from him or saw a cross look on his face when turned to her, but always a smile of love and approbation. But earthly happiness is fleeting and this happy couple knew not the change that was so soon to come and that their plans so well laid were never to be realized.” Nathan died at age twenty-four, only one year and five months after they were married. Their baby was only four and half months old. Nathan had been working in the hay field on a sultry July day when he became ill with typhoid fever, then prevalent in the community. After being "blistered, cupped and bled" for four weeks, he died. Soon after the funeral, his wife and two sisters were stricken. For three weeks, Mary Ann lay unconscious and tiny Mary Ann "was taken by a kind neighbor, Mrs. Thaddeus Twitchell, and her daughters, Roxanna and Mary Elizabeth, to be weaned."

"After a few weeks, when I was taken to the bedside of my mother and she was asked if she knew whose baby it was, she shook her head and when asked to look again, she still could not think, but as her eye wandered down to the little dress she had fashioned in love and anticipation, the truth dawned upon her and she clasped me to her bosom with tears of motherly love and affection."

Continuing with the reminiscences, Mary Ann wrote, "With the return of memory came the great weight of sorrow that had come to my mother, and she mourned as one not to be comforted, but taking up the burden of life for my sake, she wandered wearily on—still clothed in garbs of deep mourning until two years had passed away, when the glorious fight of the Gospel burst forth to illumine the souls of all who would accept its glad message."

On 4 May 1835, twelve newly ordained LDS Apostles left Kirtland, Ohio, on a mission to New York, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine as well as Ontario, Canada. They spent the next five months traveling singly or in changing pairs instructing and bolstering existing branches and proselytizing. They taught that Joseph Smith, Jr., through revelation, had restored the Church as it had been at the time of Jesus Christ. A typical day consisted of walking, hitching a ride in a wagon or taking a canal boat to a new village where, if possible, they made contact with a known member who could help find a meeting place for an evening's instruction. They usually stayed overnight and in the morning moved on to another village. According to Apostle Parley Pratt, they preached, exhorted, taught, organized, blessed the sick, baptized, confirmed and ordained.

In the early part of the summer, Apostles Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, David W. Patten and Thomas B. Marsh spoke to a small group at Rumford Point before moving to Bethel where they held a conference. During this time, Mary Ann Frost Stearns and her mother, Susan Gray Frost, were baptized by Apostle Patten. Four other members of the family eventually became members. Mary Ann's daughter said one of the most appealing facets of the Gospel for her mother was the redemption of the dead, for she deeply mourned the death of her beloved Nathan and the thought of being reunited with him was consoling.

There is also a reference to Mary Ann in a biography of David W. Patten based on his journals: "While a conference was being held at Bethel, Maine, a young woman, Mary Ann Stearns, who had been troubled for five years with an extremely aggravated case of heart disease, sent for the Elders, and upon investigation asked for baptism. David, the mouth of the confirmation, as well as in administering to her afterward for her health, made her a promise that she would be entirely restored to perfect health and soundness. She afterward became the wife of Apostle Parley P. Pratt and endured all the hardships through which the Saints were called to pass, but from that time till the time of her death in 1891, at the age of eighty-two years, she never again complained of heart trouble."

In August 1836, six apostles, including Brigham Young, Lyman Johnson and William McClellin came through Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine. They held conferences in Andover West Surplus (now part of Newry) and Bethel. They were in the area for more than a week and strongly encouraged members to gather with the main body of the Church in Kirtland, Ohio, and Far West, Missouri. In response, on 16 August 1836, David Sessions took Mary Ann and her three year old daughter to Portland in the middle of the night in a carriage because she was fearful of being prevented from leaving with other local converts who were "gathering" in Kirtland. She gave up the dowry left to her daughter by Nathan because the child's guardian refused to let her "take it to the Mormons." The next day, she joined other Maine converts and missionaries on the boat to Boston, where more members had gathered to journey to Ohio.

Kirtland was very crowded with new members. The growth was amazing and had started to cause problems with non-members as well as members. During the next eight months, Mary Ann and her daughter boarded with five different families, including those of Brigham Young and Hyrum Smith. Hyrum was Joseph Smith's brother. One woman, who lived with her husband temporarily in the same tiny home as Mary Ann, wrote in her diary the following about Mary Ann: "I admired her very much, thought her an amiable, interesting woman." That home, belonging to Sabre Granger, was one room with a dirt cellar, small pantry and closet, as well as an outdoor stove room. Mary Ann later wrote, "During this time my mother, at one of the prayer meetings in the temple received her patriarchal blessing and I received my childhood blessing into the Church of Jesus Christ of Latterday Saints."

Finally, they moved into a portion of the home vacated by Hyrum and his family when their new home was built. The Stearns then had their own private space. Several stories about Mary Ann survive from this time as later recorded by her daughter. Young Mary Ann was taught her ABC's by her mother cutting out the letters and pasting them around the fireplace. Her mother also taught her, at three, how to knit. She later recorded, "I had a pair of stockings nearly done and mother wanted me to finish them by my fourth birthday. I knit very tight and mother had knit around every other time to loosen up the stitches, but I had them done in time, and was very glad for a number [of] reasons—it is quite a task for a little active girl to sit down and knit very long at a time, and it was a great relief to have the job off my hands, as well as a pleasure to see what I had done."

Nathan Stearns had been an Ensign in the Maine militia. Mary Ann kept his blue broadcloth uniform with bright brass buttons. She often showed it to her daughter while talking about him. One day a friend told her that a Church member had been called on a mission, but was hindered by having no suitable clothing. At first she refused even to consider parting with Nathan's clothing, but her conscience would not allow her to withhold something she had that was needed by the Church. She replaced the military buttons on the jacket with regular ones and in tears gave the uniform to the missionary.

Another story reflects her character. Taking snuff was common in those days. Mary Ann was in the habit of taking a pinch at dinner from a pretty snuff box given her by her husband, Nathan. After being taught the Word of Wisdom and admonished in her Patriarchal Blessing to keep it, she placed the snuff box on the fireplace mantle and sat down to read the Book of Mormon until all desire had passed.

Young Mary Ann recorded other aspects of their live in Kirtland: "During this time we were constant attendants at meetings in the temple, and I can especially remember the fast-meetings, and can recall at this day the great power and good spirit that were experienced on those occasions—and it was generally known that Father Joseph Smith (Sr.), the Patriarch, would not break his fast and partake of food for that length of time, and that he must surely be like Abraham, the faithful that mother had told me so often about." She continued with her recollections: "I remember partaking of the Sacrament of bread and wine in the Kirtland Temple, and when I would have liked more of the wine, mother explained to me that it was in memory of the blood of our Savior when he was upon the cross. After that I was always satisfied to partake of the proper quantity—and with reverence in my heart."

Then Mary Ann's life changed radically. On 9 May 1837, six weeks after the death of his wife Thankful Halsey Pratt, Apostle Parley Parker Pratt, age 30, married Mary Ann Frost Stearns, age 28, in Hyrum Smith's home. They were married by Frederick G. Williams, first counselor to Joseph Smith. Mary Ann was described as "very tiny and very pretty." Another description recorded at that time described her as an "affectionate, well-educated, refined and ambitious woman, equal to any and every occasion." Little Mary Ann, now 4, was dressed in her newly made French lawn dress with tiny, blue flowers that matched her mother's dress. They moved into Parley's small home, a block from the new temple, for six weeks.

On 29 May, Parley and four other Church leaders were summoned to a Church Court to answer charges that they had made false accusations against Joseph Smith. These charges revolved around the failure of a Church-organized bank, the Kirtland Safety Society, and inflated Kirtland property prices. No judgements were made, and after reconsidering, Parley went to Joseph and begged for forgiveness, which was immediately granted. A month later, Parley, his new wife and daughter, left Kirtland to introduce the restored Gospel of Jesus Christ to the people of New York City.

New York and Far West Years

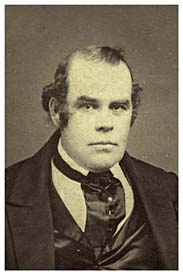

Parley Parker Pratt. Photo courtesy of Jayne Fife

Author’s note: From this point, Mary Ann Frost Stearns Pratt will simply be identified as “Mary”; her daughter will remain “Mary Ann."

Parley and Mary Frost Stearns Pratt were newlyweds of six weeks embarking on a fresh mission for the Mormon Church when they traveled from the village of Kirtland, Ohio, to the teeming port of New York City. In their two week journey, they moved through an eon of change from the recently settled countryside to cosmopolitan New York. For one dollar a day each, they boarded with the sister-in-law of the only church member in the city, Elizah Fordham. Parley immediately began writing the first missionary tract, “The Voice of Warning,” which outlined the history and doctrine of the Church. In her autobiography, Mary Ann wrote, “Brother Pratt would write a few pages, read it aloud, then Brother Fordham would copy it and prepare it for the press. During those times I would have to sit down and keep very still. I must not make noise to disturb them, but I could walk around and mother would entertain me with patchwork, cutting paper, drawing thread in pieces of cloth. Mother and I got along very well together. We were used to each other [so] that a little quiet sign language answered in most cases.”

Boarding became too expensive, so they moved into one large room that became living and meeting space. Mary Ann wrote that her mother, “being an orderly, natural housekeeper, and not afraid of work, that room was always neat and presentable at the proper hours, the large closet being a great help to that end.” Of that time, Parley later wrote, “Of all the places in which the English language is spoken, I found the City of New York to be the most difficult as to assess the minds or attentions of the people. From July to January (1838) we preached, advertised, printed, published, testified, visited, talked, prayed and wept in vain. To all appearances there was no interest or impression on the minds of the people in regard to the fullness of the Gospel . . . . We hired chapels and advertised, but the people would not hear, and the few who came went away without being interested.” They had baptized about six members, and organized a small branch that met in their rented room. Occasionally, two or three others met with them.

Near the end of November, Mary and her daughter traveled to Maine to visit family before they left New York. At the end of December, Parley, filled with discouragement, met in their living quarters with a few members to hold a last prayer meeting in preparation for their leaving. They had prayed all around when suddenly David Rogers, a chair maker, offered to spread out chairs in his warehouse and invite people to hear Parley preach. It was an immediate success; the space was crowded with people. Additional breakthroughs occurred. Parley recorded in his diary, “A clergyman came to hear me. He invited me to his house to preach, near [the] East River; he and household were obedient to the faith, with many of the members of his society. While preaching a lady solicited me to preach in her house in Willett street; ‘for,’ she said, ‘I had a dream of you and of the new Church the other night.’ Another lady wished me to preach in her house, in Grant street. In the meantime I was invited by the Free Thinkers to preach, or to give a course of lectures, in Tammany Hall. In short, it was not three weeks from the meeting in our upper room till we had fifteen preaching places in the city, all of which were filled to overflowing. We preached about eleven times a week, besides visiting from house to house. We soon commenced baptizing, and continued doing so almost during the winter and spring.”

Parley and his family left New York City for Far West, Caldwell County, Missouri, a new gathering place, in April 1838, taking a group of new converts. His younger brother, Apostle Orson Pratt, was left in charge of the now rapidly growing branch.

Mary Ann Frost Stearns Pratt and her daughter, Mary Ann Stearns Winters

Photo courtesy of Jayne Fife

They arrived in Far West in May. By this time about 10,000 church members were spread out in Caldwell, Davies and Ray counties. Collectively, they were becoming a strong political force, even the determining factor in some elections. Parley and his little family moved into an empty log cabin about nine miles out of Far West. He immediately bought and began developing a farm on a piece of land about a mile west of the cabin.

In her 1898 autobiography, Mary Ann wrote that her mother would each morning cook a meal to take to Parley and then stay to help pull and pile the tall grasses and brush to be burned during the afternoon while Parley worked on the cabin or cleared the land. In the early evening they all walked back to their temporary dwelling.

"Finally, the house of hewed logs was up to the square, a story and one half high, with a cellar beneath. We had moved into it thinking the roof would soon go on, but brother Pratt was called on a mission to some distant settlement for a week or two so my mother and I were left alone. The first night we were quite comfortable. Our bed was made on boxes and a chest, with sheets tacked up slanting over head, a few boards laid down to walk on, but the second night there came a deluge. The water came down in torrents and it thundered and lightened as though the Heavens and Earth were coming together. Our nearest neighbor was over three miles away so there was no chance of getting shelter with them. But we were alive in the morning, and the sun came out bright and shining and, hope of better times, mother put the bedding out to dry and made the best of the situation."

“About 9 o'clock our good friend father Isaac Alfred, knowing that Bro. Pratt was away, came over to see how we had fared during the storm and when he saw the cellar half full of water and our situation he said you are not going to stay here another night like this—fix up your things—pack up what you need to take with you to my house to stay till Bro. Parley comes home. I was a very timid child and the joy his words gave me it would be hard to describe even now. Accordingly he came with a gentle horse (there were no wagon roads at that time to our place) and placing my mother on it—he walking by the side, they made a very fine representation of Joseph and Mary going to Bethlehem.” [Author’s note: Mary Pratt was about eight months pregnant.]

“Bro. Pratt returned in about ten days, but decided not to return to his house as the mob had threatened to burn all the houses of Far West.” Already simmering political election issues had exploded when a fight broke out at a voting poll in Gallatin, Davies County, on August 6, as a group of Mormon men were prevented from voting by supporters of a particular candidate who was not favored by the Mormon settlers. The extent of the fight was greatly exaggerated, giving disgruntled non-Mormons an excuse to begin persecuting indiscriminately.

Parley and Mary’s son, Nathan, was born 31 August in the Alfred family’s log smoke house. When Nathan was only a few days old, they found out that their partially built cabin which had luckily been cleared of their possessions, had been destroyed by angry marauders. As soon as Mary was able, the family moved into a ten foot square log cabin in Far West that had been intended to be a cow stable.

Having been forcibly removed from their homes in Independence, Missouri, in 1833, the Mormons were determined to fight for their rights as citizens of the United States. Now, apart from the regular hit and run burning of homes, scattering of animals and destruction of Mormon crops, two Mormons, including Apostle David Patten, as well as one Missouri militiaman were killed during a skirmish at a Crooked River encampment in which Parley was involved. Soon after, a vengeful mob attacked the tiny town of Haun’s Mill near Far West, killing seventeen Mormons, including men, women and children.

Missouri Governor Wilburn Boggs issued an extermination order on 28 October. On the 31st, seven Mormon leaders, including Joseph and Hyrum Smith and Parley Pratt, who thought they were going to the state militia camp to discuss a peace settlement, were arrested and sentenced to be shot the next morning. Refusing to carry out the order, General Alexander Doniphan took them to Independence instead.

Before leaving Far West, the captives were allowed to get clothing and bid farewell to their families. Parley later wrote, “I went to my house being guarded by two or three soldiers, the cold rain was pouring without, and on entering my little cottage there lay my wife sick of a fever, with which she had been for some time confined. At her breast was our son Nathan, an infant of three months and by her side a little girl of five years. According to this account, Mary began to cry. Parley tried to comfort her, “praying for her to live for his sake and that of the children.” He “expressed hope they would meet again though years might separate us. She promised to try to live. Then I embraced and kissed the little babes and departed.”

The prisoners were taken to Independence, Missouri, and then to Richmond Jail. After a quick hearing, Joseph, Hyrum and four others were charged with treason for leading the defense of Far West. Parley and four others were charged with murder of Moses Rowland during the Crooked River skirmish and remained in the Richmond Jail.

Mary had few resources for food and fuel. She did have several cows and some stored corn, but had to depend on others, many of whom were preparing to flee. She received a letter from Parley advising her to come and live in jail with him. He wrote, “the Jail is somewhat open and cold, but the Sheriff has promised to furnish us with a good stove and plenty of wood, and we have plenty to eat—and drink. It is now at your choice to come and spend the winter with me or live a lonely widow on a desolate prairie, where you are not sure of a living or protection. If you choose to come and winter with me, you will please bring your bed and plenty of bedding so that we can hang a plenty of curtains around our bed. Bring a chest of clothing such as you need. Bring our table and 2 or 3 plates, a few basons [sic] and a wash bole [sic]. Bring all my interesting books and especially my big atlas. Bring all the wrighting [sic] paper and my steel pens; in short bring everything you think you shall need. I can pay your board and mine is found for me. You will have nothing to do but to sit down and study with me and nerse [sic] your little one, and as oft as you want to wash our clothing, you can go out to some of the nebours [sic] here [to] do our washing. I think it will be much cheeper [sic] and easyer [sic] and more comfortable for you to winter in jail with me than to live where you do. . . . you need not be a fraid [sic] of the old jail for it is better than the hut where you now live.”

Late in 1838, Mary traveled to Richmond and lived with Parley in jail. In her autobiography, she described the prison as a “damp, dark, filthy place, without ventilation, merely having a small curtain on one side.” In the prison, Mary wrote to her parents in Bethel, Maine, expressing her concerns that they would be worried about them: “do not give your selfs [sic] any trouble about us. [We] are in the hands of an all wise God and he will do with us as he pleases. . . . he will do no injustes [sic]. I feel firm in the faith of the fullness of the Gospel, and I am determined by the help of God to endure to the end that I may have a share in the celestial kingdom of God. I am glad that I am counted worthy to suffer afflictions for the Gospel sake. . . . my health is improving. The children are well. Mary Ann never so harty [sic] as she is now as lively as ever. . . . my little Nathan is a lovely child . . . he has blue eyes and looks like Mary Ann . . . dear Mother I am glad to hear that you are in good health and I trust you will be faithful and never give up the faith but endure to the end. Oh how I long to hear that my father and the rest of the family have embraced the fullness of the Gospel.”

On 16 March 1839, Mary and her children left Richmond Prison to rejoin the remaining Saints. She carried Parley’s manuscript on the Missouri persecutions, "Zion in Captivity, a Lamentation Written in Prison." It was in a pillowcase pinned between her petticoat and skirt. When she went through the doorway, her wide skirt obscured little Mary Ann, who was just behind her mother. As the child reached the opening, the guard accidentally let the heavy prison door fall on her, breaking her arm. She said in later years that because of the distraction she caused, no one thought to search her mother.

Three days later, in a letter to Mary’s parents, Parley wrote, “Mary left the prison 3 days ago and is gone to Far West from thence she will go to Quincy. . . . Mary talks often of her family. . . . while the tear stole down her cheeks and her countenance kindled with tender affection and how oft have I prest [sic] her to my heart and comforted with the hope that one day we should see you all and live in the enjoyment of your society . . .” He continued writing that Mary “is all kindness and goodness and is a pattern of patience enduring all her afflictions with a cheerful meekness and resignation and acting as an angel of mercy to her husband in bonds and imprisonment . . .”

After being threatened with death if they did not depart Far West at once, Mary and her children left with David Rogers. Their destination was Quincy, Illinois, a small city of several thousand built on limestone bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River. Upon reaching the Illinois side, they were faced with a swollen muddy stream with a firm bank on the other side. To lighten the load, Mary used a nearby crude bridge, leaving the children in the wagon. As she reached the other side, she turned and saw a little girl's bonnet floating downstream. At the same time, David Rogers, driving the horses up the bank, looked back and saw what he perceived to be a bundle of clothing that had just fallen off the wagon. He called out, “There is something lost in the water.” Mary Pratt screamed, “It is Mary Ann.”

David instantly dropped the reins and jumped into the swiftly moving water. At that instant the horses, being high spirited and active, began to run. As this incident was later recorded, “The wagon and its occupants would have dashed to pieces but for the timely interference of a large prong of a tree, which caught the carriage with such a strong hold all was brought to a stand [still].”

Tiny Mary Ann later wrote that as they moved through the deep stream, she “pitched head foremost out of the carriage and into the water.” One of the wheels ran over her and crushed her fast into the mud at the bottom of the stream. But as it moved over her, she caught the spokes with her hands. By this means the same wheels that crushed her down brought her to the surface and saved her life. Upon examination, the marks of the wheel were distinctly seen on both her thighs, which “were seriously injured and nearly broken.” Years later, she told her grandchildren that as she felt the crush of the wheel, she heard a voice say, “Hold onto the spoke, hold on to the spoke.”

Finally safe in Quincy, Mary and her children rented a small house, and by selling some books and using her cows that had been brought from Missouri for her, she was able to take care of her family. She despaired of ever seeing Parley again.

On 30 May 1839, Parley wrote from the Columbia, Boone County, Missouri jail, where he had been transferred for trial. The charge had been changed from murder to treason. He wrote that the new jail was twice as large as that in Richmond. He added that he prayed that she would “never part from me while I live. I know not how to express my feelings concerning this lon[g] absence from you and our little ones. I hardly dare to trust my fingers with a penn [sic] to write on the subject lest I should express feeling which would increase your sorrow—lest I should ask that of you which would be more than I have a right to ask of you, and more than you are bound to fulfill,—you have already had more trouble and affliction in your union with one whose life has been little else but a constant round of misfortune, grief and suffering. [It is more] than most persons have to endure during a long life. And I am far from wishing you to suffer more for my sake. If I had forseen [sic] the troubles which you would be called to endure for my sake, I would niver [sic] have asked your hand nor clasped you to my fond bosom, as my lovely brode [sic].”

In a letter to Mary’s parents in Maine, Parley urged them to come west where the Mormons were building a town at Commerce, later to be known as Nauvoo. He wrote that they should “come out and breathe the pure air of the prairies. Therefore, you can come and live with us. . . . I hope yet to see good days with my family and friends, all settled in peace where we can visit each other and rejoice together.”

Parley escaped from the Columbus Jail on 4 July 1839, with the help of his brother Orson. He had been incarcerated for eight months with no trial.

Nauvoo, England, and Back to Nauvoo

Parley P. Pratt home and store at Nauvoo, Illinois, as it appeared in 1909. Courtesy of Jayne Fife

Dramatically escaping from the Columbia, Missouri, Jail on 4 July 1839 with his brother Orson’s help, Parley immediately headed for Mary in Quincy, Illinois. Having been informed of his escape, she kept the table set for five days and nights, and a candle burning in the window. She agonized that he had been recaptured, but on the fifth night she heard a sound at the door and there he stood. She flew into his arms—both weeping tears of joy and relief. At this point, they were devoted to each other, their love made bright by the agony of suffering and separation. How then did they move through a slippery slope in their relationship so that a little more than six years later—after the birth of three more children—they became alienated from one another, with Mary refusing to accompany Parley on his westward trek?

In early July 1839, Parley wrote that he spent his first days of liberty in “the enjoyment of the society of family and friends.... After a few days spent in this way, we removed to Nauvoo, a new town about fifty miles above Quincy.... It had been appointed as a gathering place for the scattered Saints and many families were on the ground, living in the open air, or under the shade of trees, tents, wagons, etc., while others occupied a few old buildings, which had been purchased or rented.” Additional members had settled in abandoned log buildings on the opposite side of the Mississippi, in a place called Montrose, that had formerly served as a barracks for soldiers.

Parley and Apostle Heber C. Kimball cut logs and each built a small cabin on five acres of wilderness purchased from a local landowner. On 21 July, Mary wrote to her parents in Bethel, Maine: “Our healths are good, the children grow and are very play ful. I hope you will not give your selfs [sic] so much trouble about us as you have done. I presume you have more trouble about us than we have for ourselves. These light afflictions which are but for a moment will work out for us a far more exceeding [sic] and Eternal wait of glory. I have our oxen and Cows, the Lord has blest us.” She again suggests they come west and concludes with “it is towards eve and I must attend to my little babes.”

By August 29, there was a big change in plans. Parley, along with brother Orson and Hiram Clark, left Nauvoo to join other apostles on a mission to England. Mary, her two children, Mary Ann (age six) and Nathan (age one), as well as two and a half-year old Parley, Jr. (retrieved from a woman who had cared for him since the death of his mother), accompanied the three missionaries in a two-horse-drawn carriage. They were headed for New York City, where other missionaries were gathering to sail for England. After visiting Parley’s parents in Detroit, they sold the horses and carriage and steamed down Lake Erie to Buffalo, then the Erie Canal to Albany, and finally down the Hudson River to New York City—a journey of 1400 miles. Mary Ann later remembered that they first traveled over “flower decked prairies. Best of all we were free and happy—not afraid of mobs and violence—in a land of friendliness, meeting sympathy at every hand.

On 9 March 1840, Parley sailed for Liverpool, England, with Apostles Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball and Orson Pratt, as well as two others. Parley wrote in his journal, “We were accompanied to the water by my family, and by scores of the congregation.... We bade them farewell amid many tears, and taking a little boat were soon on board ship—which lay at anchor a short distance from the shore.” Mary and children traveled on to Bethel to visit her parents, returning later to New York to conduct Parley’s book selling business, including the collection of money already owed.

On 6 April 1840, Parley penned a letter to Mary giving her advice about preparing to join him by June or July. He wrote, “Here is a boundless harvest for the next 15 or 20 years...if the Lord will I expect to spend five or ten years at least.” He continued, “I wish you as soon as you get this letter, to sell every thing except beding [sic] and wearing apparel and fill two chests and a trunk and get ready to come to England the first opportunity.” He advised her to collect what was due on books and pay the printer. “Do not let the Books go without pay in and, for they cost me much money and I owe for them; and I need the remainder after the debt is paid, to support my family.” If this plan didn’t work out, he suggested she borrow money from “some good friend.... Courage Mrs. Pratt, you have performed more difficult journeys than this, and if you will take hold with Courage the Lord will bless and prosper you and our Little ones and Bring you over in Safety.”

In England, Parley’s major assignments were to edit and publish a monthly periodical, as well as a hymn book and the Book of Mormon. Brigham Young had borrowed 350 British pounds from two converts to finance the printing of 2000 Millennial Star periodicals, 3000 hymn books and 5000 Books of Mormon. While attending a general church conference in Manchester on 6 July 1840, Parley was given a letter from Mary informing him that the children were seriously ill with scarlet fever. He wrote back to her, “Behold your Letter comes with the sad news of your Sickness; and that you are not coming. This is more than I can bear. Here I must live alone, my Chamber desolate. And you still confined at home where I Could assist and comfort you and aid you continually in the care of the little ones, if I only had them here.... Why must we live separate? Why must I forever be deprived of your Society and my dear little Children? I cannot endure it.” He ended by writing that he had no prospect of coming to America for years.

Then conditions changed. His colleagues, knowing that he was slated to remain in England for several years as editor and publisher, decided he should go back to the United States and return with his family. Brigham Young gave Parley 60 British pounds to cover the cost. By the time he arrived in New York, Mary and the children had recovered. And before they set sail for England, they journeyed to Maine to visit Mary’s family. An unusual experience occurred before the arrival of the Pratt family in Maine. Mary’s sister, Lucretia Bean, told her family one day that Parley and his family would arrive at their home the next evening. In response, the next day, she changed the bedding in the best room. Her family laughed at her. They reminded her that Parley was in England and Mary in New York, but just as they were preparing for bed, the Pratts knocked on their door. As a gift, they presented a quilt that Parley had brought from England. It is now at the Bethel Historical Society.

Handmade Adam and Eve Quilt given by Parley P. Pratt and Mary Ann (Frost) Pratt

to her sister, Lucretia (Frost) Bean, and husband Samuel R. Bean in 1840.

Presented to Bethel Historical Society by Polly Ann Johnston in 2002

When they left, they took Mary’s sister Olive, age 24, with them to help care for the children. She had recently been baptized. They arrived in Manchester, England, in October. Their home at 47 Oxford Street became a meeting and lodging place for those coming and going to preach the Gospel. Parley resumed his editorship and publishing duties, and also presided over the Church in Great Britain. Mary and Olive helped in the office and assumed some missionary responsibilities.

In a letter to Church leaders in Nauvoo just after the first British edition of the Book of Mormon was published in 1841, Parley wrote, “The work is increasing in every step. I t is now prospering in Ireland and Wales, as well as in Scotland and England.” Although he missed the Saints in Nauvoo, he wrote, “I can truly say that I was never more contented, or more happy than of late.”

On 2 April 1841, at a conference held in Manchester, it was reported that there were now 8,000 to 9,000 converts—5000 just in the last year. A thousand new members had already immigrated to the United States. Passage costs were from 3 pounds, 15 shillings to 4 pounds, including provisions. Passengers were to take their own bedding and cooking utensils. All their luggage was free. On arrival in New Orleans, a passage up the Mississippi River—fifteen hundred miles by steamboat—cost 15 shillings, freight free.

In June 1841, Olivia Thankful Pratt was born and named after her aunt, Olive, and Parley’s first wife, Thankful. In 1842, the Pratts moved to Liverpool to supervise the emigration process more closely. Then, on 29 October 1842, they themselves left with 250 converts for Nauvoo. It was a challenging journey with “difficulties, murmurings and rebellions.” Parley wrote, “We then humbled ourselves and called the Lord, and he sent us a fair wind and brought us into port in time to save us from starvation. Daughter Mary Ann reported that water was so scarce that she learned to “take a bath in a teacup.”

They arrived at the mouth of the Mississippi on 1 January 1843, where they transferred to a steam-powered tugboat for the 100 mile journey to New Orleans. From there, a chartered steamboat carried immigrants to St. Louis, dropping off the Pratt family at Chester, Illinois, about 80 miles south of St. Louis, where they rented the bottom portion of an old warehouse as they waited for the river to open up to Nauvoo. Parley had been threatened with arrest if he should be caught on Missouri soil.

Near the middle of March, they took a steamer to St. Louis, gathered their group of immigrants, and boarded a small steamboat for the final 300 miles to Nauvoo. Unfortunately, they had to wait several more weeks before the ice on the river was sufficiently broken up to travel north. Finally starting, it took them two more weeks. Mary gave birth to a daughter, Susan, on the little steamboat full of converts on 5 April. They arrived at Nauvoo at 5 p.m. on 12 April. The Prophet met their boat and invited Parley, Mary and the baby to his home. Olive and the older children went to Patty Bartlett Sessions’ home.

On 15 April, Parley wrote in an article for the local newspaper, “I had been absent about three years and half during which all the improvements had been made and that by a people almost without means. Judge my feelings then, in riding through a regular town, for some three or four miles, with streets opened, lots fenced out and buildings almost innumerable, many of them were neatly built of frame or brick. I gaze, I wondered, I admired. I could hardly refrain from tears.”

In late June, Aaron and Susan Frost, Mary’s parents, arrived from Bethel, Maine, with their daughters, Sophronia and Huldah, all now members. Aaron, a skilled carpenter, began work on the Pratt’s new home, eventually laying the floors, building the stairs and fashioning the woodwork with the assistance of an English builder and carpenter, Nicholas Silcock, who had recently arrived with the Pratts. The large, two-story, nine-room home, which included a store, was built of red brick with stone window caps and sills which trimmed the 27 large windows [see photo, above]. Four-foot-square stone pillars supported a stone cornice at the entrance. There was a deep cellar in the basement. It was considered one of the finest homes in Nauvoo. It still exists on the southeast corner of Young and Wells Street, with significant revisions implemented by the Catholic Church that bought the property after the Nauvoo exodus. Mary Ann later wrote, “Before the roof was quite finished we commenced moving in and kept going from one part to the other until it was all completed.” The now large family had been living in a one room cabin across the street.

Shortly after their arrival, Joseph Smith discussed the relatively new plural marriage principle with Parley, which included the concept of marriage for Time and All Eternity, not just Time. Joseph’s restoration of ancient Church doctrine included the renewing of the traditions of Abraham and Solomon, who, he said, were commanded by God to marry plurally. He had introduced, with varying degrees of acceptance, this principle to selected leaders during the Pratt’s absence. Joseph had already chosen Elizabeth Brotherton, an English convert, to be Parley’s plural wife. Before finalizing the arrangements, he had to leave Nauvoo to visit relatives, leaving Parley and Mary to struggle with this new concept. According to Pratt family history, Parley begged Joseph before he left to not insist on his entering a polygamous marriage, but the Prophet was adamant, saying it was his duty to be an example to other leaders. He was told to pray about it. In a dream, his first wife, Thankful, came to hm and indicated that by having more wives, he would be adding to his stature in the next world, and she would be over the other wives, thus elevating her stature as well.

Mary “raged” about plural marriage, but not the sealing of couples for Time and All Eternity. After praying, she reported that “the devil had been in me until within a few days past, the Lord had shown it (plural marriage) is all right.” In the meantime, Joseph Smith had been arrested by two deputies from the Missouri governor for the reinstatement of the 1838/39 charges of treason. He had previously escaped Liberty Jail with the seeming complicity of his guards “who felt him innocent...which he was...but the vengeful governor wanted him back.”

On 24 July 1843, Hyrum Smith, recently given authority by Joseph to perform celestial marriages, sealed Parley to his first wife, Thankful, with Mary as a proxy. Then Mary was sealed and finally she “gave” (a term signifying a wife’s acceptance), to Parley, twenty-six-year-old Elizabeth Brotherton as his plural wife. She had no idea of the impact of the new arrangement.

Little Nathan Pratt, age five years and four months, died 21 December 1843 of “fever on the brain.” He was buried in the yard near the south fence of the Pratt home just seven months after the family returned to Nauvoo. Parley wrote a very poignant elegy to his son.

In the spring, Parley and other church leaders left to proselyte and electioneer for Joseph’s candidacy for President of the United States. Joseph’s decision to run was partly due to President Van Buren’s refusal to help Church members obtain compensation for the violation of their rights as American citizens and the seizure of their extensively developed land two times in Missouri. He informed church representatives, “Your cause is just, but I can do nothing for you.”

On 27 June 1844, Joseph and Hyrum Smith were murdered in the Carthage Jail. They, and the citizens of Nauvoo, had been promised protection by the governor of Illinois if they surrendered willingly, which they did. The charges made against them were later proven illegal, as other charges against them over the years always had been.

The night of the June 29 funeral, the people of Nauvoo were horrified by the appearance of a mob gathering a short distance away with the intent of terrorizing them and destroying the city. Parley and many of the leaders were away. The available men had few weapons to protect the city because Governor Thomas Ford had forced the people to surrender their weapons to his army when Joseph and Hyrum surrendered in Carthage. Now, the Governor and his army were nowhere in sight. Mary and her children, plus other neighborhood women and their children, huddled together in her large cellar room. They were certain that the horrific agony they had experienced five years previously in Missouri was about to be repeated. Then, they had been driven into the freezing countryside in the middle of winter after having been robbed, beaten, women abused, crops and homes destroyed and some killed. Young Mary Ann later recorded that her Mother softly said, “If we have to be killed, let us all die together.”

One woman later wrote about a drum beat that penetrated the night, “Every blow seemed to strike to my heart...the women...were weeping and praying.” Near midnight, there was a sudden flash of lightening and a crash of thunder, followed by a violent storm. Amazingly, the mob dispersed.

Amidst all the tumult of that time, little daughter Susan, aged one year five and one half months, died of disease of the bowels on 28 August and was buried next to her brother who had died just eight months before. Mary’s sister Sophronia had died in May. The murder of Joseph and Hyrum had also taken their toll on Mary.

On 9 September, twelve days after Susan’s death, Parley took his fourth wife (second plural wife), Mary Wood. Mary Pratt did not participate in this marriage as before, so she may not have been aware of it. For whatever reason, Mary was not present at any of Parley’s marriages other than that of Elizabeth Brotherton. Could Parley have decided that Thankful Halsey Pratt held the position of “first wife” even though she was deceased and he therefore did not require Mary’s approval and participation? Although the approval of the first wife was common in Nauvoo, it was not firmly established by Brigham Young until the arrival in the Salt Lake valley.

In November 1844, Parley married twice more and took his new wife, Belinda Marden, with him on a mission to New York. Mary gave birth to her last child, Moroni, six days after he left. About a week later, she received a letter from Parley. He wrote, “I never left home with more intense feelings, nor under more trying circumstances than present, except the time I went to prison and to death leaving you sick of a fever with a babe three months old and to the mercy of savages and scarce shelter or food. I was sorry to go and your tears quite overcame me. But I tore myself away and here I am. And where I hope to go I hope you will soon be also. I shall then be happy; so cheer up. The time will soon pass with you, surrounded as you are with Mother, children, and friends. But with me it is far different. I not only have to part with one but all. Time drags slowly and solitude is sickening to me....” Tellingly, there was no mention of Belinda—only solitude.

After eight and a half months, Parley and Belinda returned. She later wrote, I “went to Mr. Bench’s tavern to board while Parley went home. After a little time, it was arranged for his wife Mary (Wood) and me to commence keeping house in a room upstairs in Mr. Pratt’s house.”

This was a tumultuous time in Nauvoo. As early as the winter of 1844, Joseph Smith had begun plans to search for an additional gathering place in the West. In September 1845, church enemies set fires to settlements surrounding Nauvoo, causing refugees to stream into the city. Parley was active in planning for the exodus. At the General Council meeting he provided a list of necessary items for a family of five to cross the plains. In early October, a formal government document called the Quincy Convention demanded that the Saints leave Nauvoo by May 1846. Earlier, on 6 October 1845, at the first conference held in the Nauvoo Temple, those attending were given instructions for a spring departure. Several companies were also organized.

During that harried time, Mary had other things on her mind. Her sister, Olive Frost, who was only thirty, died. She had never been strong and her health deteriorated in England. On 25 September, she became ill with malaria and after two weeks of chills and fever, she died of pneumonia.

On 10 December, leaders and their wives received the sacred ordinances given to worthy members. Even though they would have to leave soon, receiving these blessings was of great importance. Mary was one of about twenty women to supervise the preliminary ordinances in the women’s area.

On 27 December, a Marshall appeared in Nauvoo with warrants for the arrest of the Twelve Apostles.

Word was received on 17 January that Governor Ford was intending to place Nauvoo under martial law, and on the 29th state troopers arrived in Nauvoo seeking to arrest church leaders. Two days later, the leaders met and agreed that they had to start westward immediately. Boats were made ready and all their families were told to be ready to leave within four hours of being notified. The first exodus group with six wagons crossed the Mississippi on February 6.

Parley married his eighth wife, and sixth plural wife, on February 8. He left Nauvoo on 14 February with his family of seven wives and six children: Nephi (six weeks), Alma (six months), Mary Ann (13), Parley, Jr. (9), Olivia (4 ½ ) and Moroni (fourteen months). It is probable that Mary did not know of the existence of most of these wives. The group also included teamsters for their three ox-driven wagons. They also had a one-horse drawn carriage. Crossing a river on ice, they slept for several nights in tents and wagons. There were two to three inches of snow on the ground, and it was very cold.

They then moved a few miles to a log granary which had been a tithing collection building. There was a bin full of corn at one end and a pile of potatoes in the basement that supplied needed food for them and their animals. The main group was located more than a mile ahead of Sugar Creek where Brigham Young was waiting for more members in order to organize traveling companies. Parley traveled back and forth for meetings. It was bitter cold, alternatively raining and snowing. Most people slept in tents and wagons, or under wagons. Almost a week out, Parley decided to return to Nauvoo for some wagon fittings he would need for the long journey. He took Mary and little Moroni, who had been suffering with a bad cough, to see her parents and sister who remained in the Pratt’s home. Aaron was still laboring on the interior of the Temple. When it was finished, they intended to return to Maine.

The blacksmith was too busy to fill Parley’s request that day, so he left Mary and returned to camp. Two days later he returned for her, but the river was full of icy mush and impossible to cross by ferry. As there were many people going to and from Nauvoo at that time, when the river conditions improved Mary was able to reach their camp on her own. She had left Moroni with her parents. Gathering her two daughters, Mary Ann and Olivia, she returned to Nauvoo, telling Parley that they would catch up when the frigid weather was over. She had lost two children and two sisters to illness in the last two years. She was taking no chances. Her surviving children were her main concern now. One might also assume that living in such close quarters with six other wives proved a difficult, if not unbearable situation for her.

By the end of May, according to Mary Ann’s autobiography, “The main body of the Church had left Nauvoo and for a time, peace and quiet reigned in the city. We individually were waiting for our house to be sold that we might pursue our journey....”

On 10 September 1846, a mob advanced on the city to drive out the last remnant of the Mormon population, which generally consisted of the poorest citizens. The city was only lightly fortified. There was a battle, during which three male residents were killed. For safety, a large group of women and children had gathered at the Pratt home. Anson Pratt, Parley’s brother, asked Mary to supervise the baking of bread for the defenders to last throughout the crisis. Finally on 15 September, it was agreed that the remaining Mormons would leave the city in three days. Only a few men, their clerks and their families were allowed to stay to continue to try to sell property, but, as in Missouri, most residents received nothing. After they left, people came in and took what they wanted.

Three days later, Mary and children were picked up and deposited on the edge of the Mississippi River where they spent the night. As they were preparing their camp, they heard a martial band and members of the mob marching their way. Young Mary Ann later recorded, “Just as they were opposite our camp, they halted an instant, and the captain shouted, ‘You’re a d–d pretty looking set, ain’t you? . . . My Mother took a step forward and replied, ‘Gentlemen, it is your day now, but it will be ours by and by.’ He called back, ‘Shut up that, or we will have you under guard.’ She returned, ‘I do not fear you, Sir,’ just as they were passing.”

The next day they crossed the river to Iowa on a flat boat where they camped on the riverbank a mile above Montrose with Parley’s mother, Charity, his two brothers, Anson and William, their families, and about three hundred refugees. Supplies were scant. A flock of birds landing nearby provided immediate relief and then a boat with flour, sugar, coffee, rice, dried apples and bacon came up the river from St. Louis, kind people there having been alerted to their dilemma. Word also had reached Brigham Young, and he dispatched teams, wagons, tents and provisions.

William Pratt’s little daughter, Martha, was ill and soon died. It was decided to take her back to Nauvoo to be buried in Parley and Mary’s yard with the other children. When they did this, the were amazed at how quiet Nauvoo was. The mob, having accomplished their purpose, had disappeared, so Mary and her children returned. This time they lived with one of the church agents left to arrange the sale of property.

Nauvoo, Bethel and Across the Plains to Utah

On 7 October 1846, Brigham Young sent a letter from Winter Quarters, Nebraska, to Mary Pratt, who was living in a tent on the western shore of the Mississippi River. Young wrote that he had authorized one of the Church’s agents left in Nauvoo to arrange for her to travel to Winter Quarters. But Mary chose to cross the river back to Nauvoo and remain there all winter. She moved, with others, into the former home of John D. Lee, who later wrote: “My large house, costing me $8000 . . . I was offered $800 for. My fanaticism would not allow me to take that for it. I locked it up, selling only one stove out of it, [for] which I received eighty yards of cloth. The building with its twenty-seven rooms, I turned over to the committee, to be sold to help the poor away. The committee informed afterwards that they sold the house for $12.50.”

In early June 1847, Mary and her children traveled to Winter Quarters, to tell Parley that they were returning to Maine. Parley had just started the journey west as one of the leaders of the second company, but rode a horse back to meet with her. He authorized his agent to provide her with some funds when their house sold, which he later accused her of taking and wasting. Mary remained in Winter Quarters.

Ten months later (April 1848), Mary was given $200 by Church authorities. This was half the money left from the sale of their home after Parley’s debts had been paid. The other half was given to Parley’s brother, Anson, for the care of their mother, Charity, and his family.

On receipt of these funds, Mary and her three children, Mary Ann (age 15), Olivia (age 6) and Moroni (age 3 ½ ) left for Bethel, Maine, where they lived with her parents. Daughter Mary Ann joined her cousins, Melvina and Nancy, daughters of Theodore Stearns, at the Gould Classical and English Academy. Family tradition indicates that her grandparents, Charles and Thankful Bartlett Stearns, paid each term’s tuition of two dollars and fifty cents with the hope that she would not go back to the Mormons.

The Academy had been reopened in 1848 under the administration of its founder Dr. Nathaniel Tuckerman True (1812-1887). The fall of 1849 catalogue listed 160 students from many towns in Maine, as well as New Hampshire and Massachusetts. There were three departments: Classics, Common English and High English. The Classics Department included the study of Greek and Latin literature and languages. The Common English Department classes included Exercises in Reading and Declamation, Smith’s Geography, Smith’s and Weld’s Parsing (grammar) Book, arithmetic, bookkeeping and penmanship. Finally, students in the High English Department had a variety of class choices, different each year. Each term, one or more of the following lecture courses were taught. In the natural science were offered courses in human and comparative physiology, mineralogy, geology, physical geography, botany, astronomy, and chemistry. Mental and moral science courses included rhetoric, philosophy, and moral science, while mathematics courses alternated among algebra, geometry, trigonometry, surveying, navigation, analytic geometry, and mechanics. French, Spanish, Italian and German were available to all. The fall 1849 catalogue announced that during 1850, “Lectures, and such other exercises will be introduced, as shall best fit Teachers for the duties of the schoolroom.” It made an additional assurance that “students have access to the most valuable works on teaching, which have been published in this country.”

There are no records of Mary Ann’s classes, but it is probable that she was in the Common English program and took advantage of the teaching course because she became a well-known central Utah teacher.

According to Mary’s son Moroni’s biography, their New England relatives were very kind to them and offered “land and money if they would give up the Mormon religion and remain with them.” But, in 1851, she and her three children left Bethel, possibly on the newly established Atlantic and St. Lawrence Railroad, which had first arrived in Bethel from Portland on 10 March of that year. The one way fare was $2. Stopping with friends in St. Louis, Missouri, long enough for the children to attend school, they arrived in Kanesville, Iowa, in January of 1852, determined to cross the plains to the Utah Territory.

They had no idea how they could afford the wagon and supplies required for the three month journey. In the meantime, they supported themselves by baking bread, and then slicing and drying it in an oven. It was sold to California bound emigrants for food when it was not convenient to cook. They also made cotton flour sacks for emigrants to store food supplies in, which they sold at 75 cents per hundred. They made orange and blue calico shirts with ruffled necks and wrists for a group of Native Americans being taken by a church member to Washington, D.C., to meet the President.

At the beginning of May 1852, they were assigned to a wagon train, the 12th to be leaving that year. Within days, two friends who were not yet traveling west appeared at her door to inform her that they had put enough money in the Emigration Fund to supply her with a wagon and necessary provisions. A non-member grocery store owner sent word that if she would come personally to his business, he would give her $10 worth of food. Despite the fact that she had never been in his store because he sold liquor, she did go this time and was given cornmeal, bacon, rice, dried codfish, dried fruit, soap, and a few other things. Days later she was introduced to a Scottish emigrant, David Murie, and his twelve year old son, Jimmie, who managed to buy a yoke of untrained oxen, but had no wagon.

On 10 June, they started west with members of the Harmon Cutler Company, which eventually included 262 persons, 63 wagons, 17 horses, 231 oxen, 171 cows, 154 sheep, and 20 dogs. Early on, they found that their load was too heavy. This presented the difficult task of choosing which items to leave behind. They also were given a second yoke of oxen which turned out to be as untrained as their original team. The four animals were soon out of control, alternately stopping still or running wildly in circles, while David hung on valiantly and Mary frantically ran alongside the wagon picking up supplies falling in all directions. Once, the cattle turned quickly and sharply, nearly crushing her between their bodies and the wagon. They had fallen behind the rest of the group. Finally, a young teamster/scout, Oscar Winters, whom they had known in Nauvoo, found them stalled in the middle of the road. He took over both of the teams and insisted on driving them to the river crossing. By the time they arrived, David had a better understanding of how to control them.

Cholera struck the company one evening after a rope-ferry crossing. Several men had been in the warm river all day steadying the raft and had liberally drunk the water. Mary used her homemade concoction of “charcoal and molasses, landanum and paregoric, camphor and a little cayenne pepper with as much raw flour as charcoal, and it proved to be a good remedy, for all that took it recovered except one older man.”

A group, with about twenty wagons, including Mary and her family, decided to move ahead as more and more members of the larger group were suffering with cholera. Despite occasional violent rain and wind storms, they “plodded on day after day, sometimes making a fifteen mile drive but oftener twenty—no hurry—you could not change the gait of the oxen, but had to wait patiently their motion.” It was clear that there was “no danger of getting left [since] most anyone can walk as fast a yoke of oxen can travel.” The others never caught up. It was later reported that the group behind was attacked by Indians, and all their horses were stolen, leaving them frightened, but alive.

Oscar Winters and Mary Ann Stearns Winters

Courtesy of Jayne Fife

Mary Ann wrote in her autobiography that their team had settled down and finally made steady progress. The women could now knit and sew comfortably in the wagon, as the ground was quite level and the oxen were under control. She acknowledged the change: “Our morning’s milk we put in our tea kettle, placed a cloth under the cover, put a cork in the spout, tied a cloth over that and tied it to the reach under the wagon; and no matter how hot the day was, the draft under the wagon made it very comfortable for our dinner, for there was a piece of butter the size of a teaspoon which was very fresh and sweet and the children took turns having it on bread.”

On 16 August 1852, just before reaching their destination, the group came to a beautiful grove of trees at Deer Creek, now in Wyoming, where they discovered a primitive wooden stand and benches. The “sight of it was inspiring to the emigrants for it really looked like going to meeting again as they were used to doing in the groves and boweries before they started on their journey, and all moved around with cheerful quietness and reverence for it seemed a visible testimony that God was with us and leading us on. There was a sacredness about it all that subdued all sounds and strengthened and encouraged to renew diligence. All labors were hastened to prepare for the Sabbath; the tires were wedged and tightened, the repairs completed, washing and cooking done and all retired to rest, but with the early dawn all were stirring again for the birds were singing a Sabbath chorus of praise.

“In the grove every heart was light and joyous for we now had passed the sickly portion of the journey and were nearing the goal of our hopes and desires. The sun arose on a scene of calmness and beauty. After the quiet breakfast and at a given signal all repaired to the grove with happy hearts to listen to the words of inspiration. . . . That familiar hymn, ‘How Firm a Foundation’ was sung, and after prayer by one of the aged brethren, and another hymn, testimonies were borne and counsel and instruction given by the Captain. . . . After the close of the meeting and the noon luncheon had been partaken of they enjoyed a season of quiet rest until the lowering sun.

“Just as the evening meal was about ready, a carriage was espied coming from the east. . . . it was Apostle Lorenzo Snow just returning from his mission to Italy. He was making a rapid journey across the plains with a carriage and horses, stopping with the camps overnight and traveling on to the next in the daytime.”

At that point, a romance which had budded during the last days in Nauvoo and blossomed during the journey west, culminated at Deer Creek. That evening, Apostle Snow married scout and teamster Oscar Winters, age 27, to Mary Ann Stearns, age 19. Mary Ann later wrote that she wore a green gingham dress and worried that she had no looking glass to make certain that her hair was arranged perfectly. Their wedding meal was “bread baked on a bake skillet, a piece of meat, a little lump of fresh butter with a cup of cold water.” Her wedding gift from her husband was a dollar to buy a few necessities when they arrived in Salt Lake. Over the years, family members have celebrated this event by recalling, “a Snow married a Winters to a Frost ” (Mary Ann’s mother’s maiden name).

Arriving in Salt Lake in early September 1852, Oscar and Mary Ann Stearns Winters were immediately sent to Battle Creek, a new settlement forty miles south of Salt Lake City. Mary, Olivia and Moroni remained with friends in Salt Lake. After Brigham Young approved her divorce from Parley in March 1853, she and the children settled into a small log cabin at the southwest corner of the new fort in Battle Creek.

In 1854, Parley stopped in Battle Creek on his way to another mission in California. Mary was present at the talk he gave to residents, but he recorded in his journal that they did not speak, although he did visit with his children and present them with gifts. He further wrote that Mary was now his enemy.

Parley was murdered in Arkansas on 12 May 1857, as he returned from a mission in the northeastern part of the United States. He was only fifty years old. He left behind 9 wives and 30 children, including Olivia and Moroni, but not counting Mary and another wife who had left him before his divorce from Mary.

Olivia was almost sixteen when she married Benjamin Driggs on 16 February 1857. They had twelve children. Over the years, Benjamin worked with his wheelwright father, served in the militia that faced off Johnston’s Army near Fort Bridger and was a participant in the 1866 Black Hawk Indian War in central Utah. He was also a blacksmith, a contractor for grading a portion of the Union Pacific Railroad, as well as a successful local merchant. He had a second wife and served, under the Edmunds-Tucker Act, six months in the Territorial Penitentiary as a result.

Moroni married Caroline Beebe and raised ten children. Most of his education was obtained from his mother and stepsister, Mary Ann. He was an avid reader and had a natural talent for music, manifested by his conducting an orchestra for many years, as well as excelling on the violin. At some point, he invested in ox teams and wagons, and was one of the drivers that moved back and forth across the Plains to the Missouri River, carrying supplies as well as emigrants. As a member of the militia that fought the Black Hawk Indian War of 1866, he was later made an honorary Adjutant General for his efforts to obtain federal pensions for the participants. Five years after his death, survivors finally received compensation. He served Church missions to New England and England in between operating a saw mill in American Fork Canyon.

Except for four years when Mary traveled with Oscar, Mary Ann and their growing family as they served a mission to teach school in several newly formed central Utah town, they remained in Battle Creek, which eventually became Pleasant Grove. Oscar and two sons developed a farm and a molasses mill using sap from maple trees growing abundantly in the nearby canyon. Mary Ann taught school in their home. Their five daughters received advanced education and later taught school. Two of them married LDS apostles, one of whom, Heber J. Grant, became the seventh President of the Church.

Mary served for years as the only midwife in town. According to a granddaughter, “out of the hundreds of births at which she assisted, she never lost a single case.” She used medicinal herbs, roots, bark, leaves, and seeds from her own garden or those she gathered around the countryside. Some of her choices were tansy, horehound, peppermint, rhubarb root, sage, catnip, kinnikinnick bark, Indian root, yarrow, and raspberry leaves which were dried and powdered. Medicinal powers were lost unless each item was obtained at the correct time of the year and properly cured. She had her own recipes for soothing teas, salves and lotions.

Her granddaughter, Augusta, once wrote that Mary was “by nature energetic, self-reliant, and blessed with enormous energy. She took charge of everything and everybody, even my tiny mother who was little bigger than a child, and who always depended on her for aid and advice.” In his biography, Moroni described his mother as “an affectionate, well educated, refined and ambitious woman, equal to any and every occasion.” When she wasn’t tending to a birth, she often could be found carding, spinning, dyeing and weaving wool. She also spun and wove flax from which she made yards and yards of fine lace “netting” for trimming undergarments or hand-woven linen squares.

Mary Ann Frost Stearns Pratt died on 24 August 1891. Her tombstone reads: “Her dear weary head is at rest. Its thinking and aching are ‘ore. Her quiet immovable breast is heaved by afflictions no more.”