Bowler versus Chisholm, and the Ill-fated Bethel-Rumford Electric Railway

Title

Creator

Source

Publisher

Date

Format

Identifier

Text Record

Subjects

Collection

Full Text

Bowler versus Chisholm,

and the Ill-fated Bethel-Rumford Electric Railway

by Randall H. Bennett

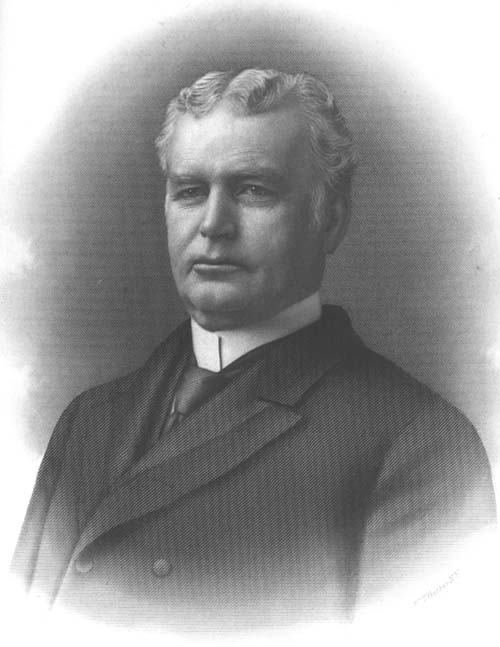

In 1882, Canadian-born Hugh J. Chisholm (1847-1912), a lumber enthusiast and successful partner in the Portland based Chisholm Brothers Company—producers and distributors of the popular lithographed view books of United States and Canadian scenery, and, in 1884, the first picture postcards in the country—visited the “Great Falls” at Rumford, Maine, for the first time. Looking back at this visit, he later wrote, “To my mind there came a great possibility, and a great desire to participate in the success and possible development of Rumford Falls. From that moment I was seized with a desire to develop this great water power and within myself made a solemn resolve that no obstacle, be what it may, should stop me in what I was determined to carry out.” Twenty five years later, Chisholm’s determination to organize and control life at Rumford Falls met a bold challenge, one which attracted state-wide attention to this busy metropolis that a quarter century earlier had been not much more than “the falls and a berry pasture.” The changes that led to the late 19th century development of Rumford Falls as a center for the production of paper reveal the dramatic transformation of a town that had long depended upon agriculture more than any other economic activity for the livelihoods of its citizens. Beginning with the first engineering study in 1883 of the Falls (the highest east of Niagara), Chisholm initiated a strategy to acquire, through his local agent Waldo Pettengill (1844-1926), over 1400 acres on both sides of the Androscoggin River, thereby securing for his interests adequate tracts for mill sites, along with locations for businesses and residences. By August 1890, he and his associates had purchased the necessary land, and they moved ahead to organize the Rumford Falls Power Company with a half million dollar capitalization. Initially, there was a great drive to introduce new businesses to Chisholm’s “model town.” Dams were constructed, canals dug, and an illustrated booklet authorized by the Power Company to attract prospective business ventures (particularly in manufacturing) was published. Although Rumford Falls never became a center for the production of textiles, the Power Company brochure cited capabilities in water power “to run over 1,800,000 spindles or more than 3,800 wool cards.”

Hugh J. Chisholm

As the founder of the Somerset Fiber Company at Fairfield on the Kennebec and, by 1881, of the Umbagog Pulp Company at Livermore Falls on the Androscoggin, Hugh Chisholm was the dominant figure in a large number of local concerns by 1900. They included the Rumford Falls Power Company (of which he was a director), the Rumford Falls Sulphite Company, the Rumford Falls Boom Company, the Rumford Falls Light and Water Company, the Rumford Falls Woolen Company, the International Paper Company, the Continental Bag Company, the Rumford Realty Company, the Rumford Publishing Company, and, of course, Oxford Paper Company (now NewPage), the last mill to be organized under his authority. Moreover, the industrialist or one of his “lieutenants,” as they came to called, also controlled the major transportation facilities into Rumford—namely the Portland and Rumford Falls Railway (derisively called by some at the time “two streaks of rust and a right-of-way”), as well as a line from Rumford to Rangeley which hauled passengers in the summer and pulpwood in the winter. In addition, two banks fell under Chisholm’s control, while the Power Company purchased lands and rented property within sight of the smoke belching mills at increasingly burdensome prices.

These observations, of course, should not be interpreted as signifying a general lack of appreciation for Chisholm’s efforts and accomplishments at Rumford Falls. Hundreds of mill workers, many directed north to Oxford County by paper company agents on the premise that they would be steadily employed, could usually be counted on to express their gratitude for all these benefits which came to pass under his constant supervision. However, a certain degree of Yankee skepticism regarding such a highly planned development engendered a less favorable impression of Chisholm, particularly among Rumford’s longtime residents, many of whom had sold land to Pettengill without grasping the underlying plan. Complaints of fixed wages, along with the high cost of rents or home ownership, led one critic to note the feudalistic quality of the development: “Rumford Falls itself is just that curious, jammed-together island full of tall city blocks, with tall modern improvements, hemmed in by rushing water and wild woods. It makes one think of those medieval garrison towns on inaccessible islands; if its bridges were destroyed, it would be a hard place to capture by assault.”

The organ for the Chisholm interests had been, since 1894, the Rumford Falls Times, under the editorship of Edgar N. Carver and later Tracy Barker. This newspaper, founded in 1883 as the Canton Telephone, moved a few years later to Dixfield to become the Dixfield Telephone. Carver had followed with particular interest the purchase of lands at Rumford Falls and vicinity, and, seizing an opportunity, renamed the paper for a third time and relocated it once more. For over a decade, the Times was the most popular newspaper in the community. However, there must have been much excitement when, in 1906, a brightly lettered sign appeared on the side of Congress Street’s Strathglass Building with the title, The Rumford Citizen.

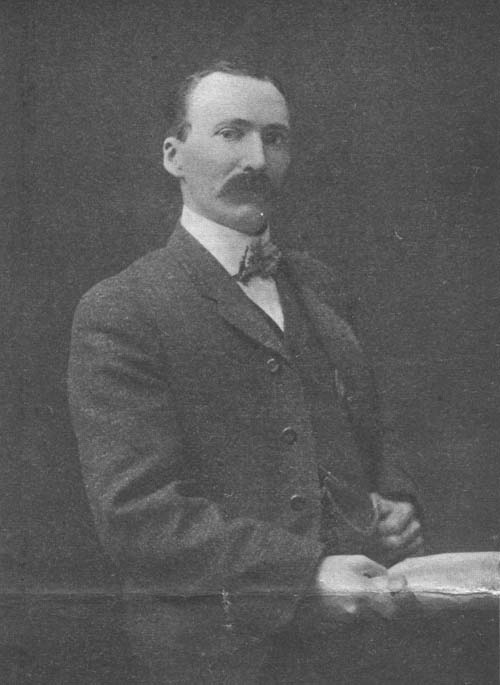

A complete run of the short-lived Rumford Citizen exists in the Bethel Citizen’s archives (a microfilm copy is held by the Bethel Historical Society), throwing light on a political struggle that developed between certain factions at Rumford Falls and the neighboring town of Bethel during this period. The founder and editor of the Rumford Citizen, Ernest C. Bowler, came to Bethel from Palermo, Maine, and later was destined to assume the post of business manager of the Portland Herald, which merged in 1921 with the Portland Daily Press to form the Portland Press Herald.

Ernest C. Bowler

Twenty-five miles upriver of Rumford at Bethel, with its “neatly kept homes and broad streets overarched with long lines of elms,” Bowler had become part owner of the Bethel News—then a four page local weekly—in September 1897. The following March, he acquired the remainder of the business from Aked D. Ellingwood and immediately began an ambitious program to enlarge the paper and add a book plant. In an article in a special edition of the Bethel News, Bowler attempted to emphasize his adopted town’s virtues in contrast to the larger settlement adjoining Bethel on the east: “Although Bethel has several manufacturing industries, yet it is not in the modern sense a manufacturing town. There is no foreign element gathered on the outskirts, no hideous row of corporation tenements, no sharp contrasts between wealth and poverty; an Academy town, it has its own appreciation of intellectual and social life.” No record exists of Hugh Chisholm’s reaction to this indirect “assault” on Rumford, but Bowler’s advocacy and strong endorsement in the Rumford Citizen of a proposed electric railway between the towns of Bethel and Rumford obviously posed a threat to the transportation monopoly already in place at Rumford Falls. Chisholm therefore had no choice, but to become involved in what from his view was a threat to his vision of the place he wanted to create at Rumford Falls.

Three months after its first issue appeared, the Rumford Citizen carried an editorial endorsement of an elaborate scheme to run an electric railway along the Androscoggin River from Rumford Falls to Bethel Hill. Citing the unusually high freight rates on the present railway that passed through Mechanic Falls, Bowler noted that workers were being forced into outlying areas to build their homes, while the mills, lumber companies, the Power Company, and the Rumford Falls Realty Company owned and controlled all the property at Rumford Falls. Furthermore, Bowler made it known that success for the newly organized “Rumford Falls and Bethel Street Railway Company” could only be assured when certain “obstacles” had been overcome at the Falls. The proposed route of the electric railway was to begin in Ridlonville, a residential neighborhood in Mexico, and by heading west one would travel through Rumford, Hanover, Newry and, finally, Bethel, where the line would terminate at the head of Main Street near the Bethel Common. In addition, a branch line was planned to serve Andover Village. Such a public utility would naturally increase the value of property in Bethel, as well as any along the line. It was also promoted as a means of saving a considerable sum of money in transportation costs by carrying mail, freight and passengers in the smaller communities between the two railheads. Moreover, the town of Andover, placed at a disadvantage as a stopping-off point on the route to the Rangeley Lakes by the construction of Chisholm’s Oquossuc branch of the Portland and Rumford Railroad, would regain its former popularity with summer visitors were the electric railway built.

Hugh Chisholm’s newspaper, The Rumford Falls Times

During September 1906, the Rumford Citizen began closely following the proposed railway project. Incorporated that month, the Railway Company made immediate plans for survey work. Of “regular steam road gauge,” the tracks would pass by ten or twelve saw mills on their course along the Androscoggin and its tributaries, and in doing so, would greatly increase timberland values. Touted as the most significant public utility venture since the arrival of the pulp and paper industry at Rumford, the electric line had on its Board of Directors several prominent merchants from the Falls, including Elliot W. Howe, Orville J. Gonya, and, as president of the Board, Everett K. Day, whose department store (the largest in western Maine) was housed in the Strathglass Block ("Hotel Harris"). Although no direct financial interest was reported between Bowler and the railway, one of his editorials provides a clear idea of his position: “The Citizen will champion this enterprise. It has been in touch with the various moves which have been made during the past few months, but the best interests of the project have seemed to demand that nothing be said until the present time.”

Recognizing the unsettled atmosphere now created, one farmer who supported the line declared, “Don’t you worry about getting help to lay that road. We’ll all turn out and dig if necessary.” Indeed, if Everett Day’s railway experience with a line he supported in Hallowell was any indication of the Rumford-Bethel line’s future prospects, things were about to turn for the better. But Hugh Chisholm’s vision for the centralization of the bustling community was now threatened with talk of “going into the country to get acquainted with your neighbors” and of scenic parks in rural Rumford set aside for the benefit of the working class. Without delay, Chisholm and Charles A. Mixer, agent for the Power Company, called a meeting during which the subject of the Falls as a residential village was discussed. In an unexpected, but transparently calculated move, Chisholm authorized Mixer to allow the heads of the Electric Railway Company to sell twenty seven lots for home-building purposes. Lots under the Power Company’s control would be sold with “restrictions, which Mr. Chisholm thinks necessary to insure the fulfillment of his purposes.” Among these qualifications was a restriction on the building of homes deemed “not in keeping with the neighborhood.” Mixer was also quick to come to Chisholm’s defense, assuring his listeners by declaring that “Mr. Chisholm had this or some similar plan in view from the beginning.” Initially, both the Citizen and the Times appeared in agreement regarding the advantages of the proposed railway between Bethel and Rumford. After all, some fifteen years prior to this time, a steamer on the Androscoggin had successfully made its way between the two towns. However, the electric railway was considered a more permanent addition to public transportation, and, realizing that the Grand Trunk Railway already served Bethel, the Times soon began to waiver in its enthusiasm for the project. Earlier, the same newspaper had suggested that those traveling from Bethel to Norway (by way of the Grand Trunk) to do business, might consider coming to Rumford instead. What undoubtedly changed the Times’ sentiment was the knowledge that people in the villages along the line would likely travel to Bethel and then to the Oxford Hills area rather than to Rumford. In September 1906, actual surveys of the railway were made under the supervision of John A. Jones of Lewiston, who noted, “Not one locality in Maine offers such inducements to the electric railroad builder, as does this one.” Comparing the several hours of travel time by horse or car to the swift one hour trip proposed by rail, Jones stated that the location along the river would allow a higher rate of speed than other Maine lines of comparative length. Soon, word spread throughout the countryside of recreational parks, of new hotels (one costing $20,000 was planned, but never built), and improved markets for locally grown goods. During all this discussion, the Rumford Citizen continued to remind readers of such benefits.

Ernest C. Bowler made a point in his editorials to emphasize the dramatic increase in Rumford’s liquor traffic, the seemingly “fixed” appointments of public officers, and the suggestion of moving the county seat from South Paris to Rumford as an ill-conceived one. To Mixer’s line in the Times, “Mr. Chisholm’s ideas have not always been to his profit, although beneficial to the town,” Bowler replied, “The Citizen hails with pleasure this movement towards the amelioration of conditions that were creating such uneasiness.” Throughout these challenges, Bowler liked to call his product a “peoples paper,” and during the next two years he continued to print in Bethel his columns attacking one-man rule at Rumford Falls.

By early 1907, hearings had been held in most of the towns along the proposed railway line, to allow a right-of-way to be granted for the electric railway construction on property owned by the several towns. In Bethel, crowds attended one large meeting in the Cole Block’s Odeon Hall to proclaim the line and the nearly certain possibility of finally having electricity in the town. As one Bethelite noted later, “There were no kickers or cold water throwers in evidence.” Meanwhile, back in Rumford, tempers were rising and factions were obviously developing. Colonel George Bisbee, speaking at one hearing on behalf of the Chisholm interests, wanted nothing to do with the line and stressed an added cost to taxpayers for new bridges, the repair of damaged water lines and general maintenance of streets the railway would need to use. He was soon further outraged when several lists of supporters were produced. In the end, only a few businessmen refused to sign in favor of the line. The next day, scores of people made their way to the Strathglass Block to congratulate Bowler on his coverage of the hearing, for the voters had, not surprisingly, approved the use of Rumford streets and bridges late the night before.

Bowler’s newspaper, The Rumford Citizen

In January 1907, a clear sign of growing trouble over the electric railway idea made itself known when several local Rumford businessmen resigned as officers of the Rumford National Bank in response to pressure to refrain from further support of the railroad venture. The Rumford Citizen carried the story with praise for the resignations. Under the heading, “Fierce Gale,” the paper also provided an account of how one evening, soon thereafter, a window of the E. K. Day store was blown in and the resulting current of air soon “blew” two more out on the opposite side of the building. Hinting of damage due to something other than ”natural causes,” another news item recounted the destruction of a huge window in the Gonya Brothers Store. It seems the store sign had made its way through the window on the same gust of wind! Future issues of the Rumford Citizen included similar commentaries, while the Times remained strangely silent. A. J. H. McKeeman, a strong railway supporter in the town, while riding with one of Chisholm’s mill managers in a sleigh, was struck by a log and knocked to the ground, receiving serious injury. Of the incident and Chisholm’s employee, a fellow named Palmer, the Citizen recorded, “Mr. Palmer escaped without injury except he seemed to have lost his senses, for he was sought out by the Citizen man and for some reason seemed decidedly tongue-tied. We trust he will regain his speech.”

Under the name “Commoner,” one writer in Bowler’s paper issued declarations weekly against everything from high postal rates to the horror of tenement life, and always with the finger of guilt pointed squarely in Chisholm’s direction. Bowler himself warned of the possibility of the Railroad Commissioners denying a charter for the electric railway under “guidance” from certain factions. As 1907 waned, it was only too apparent that little actual work on the line would be done as long as Rumford remained in such turmoil. One of the major issues of that year had been the election of selectmen for the town of Rumford. As there, again, were those in favor of the electric line and those against, speeches and political leaflets were very much in vogue. In the end, it was made known (in every possible manner) to mill laborers exactly how much they might “pay” to have the railway built and also what Hugh Chisholm’s sentiments were in the matter. As a result, the anti-railway forces were victorious in the municipal elections.

Though articles describing work on the electric railway survey and continued efforts to purchase land along the route appeared sporadically in both Rumford papers, perhaps the circumstance that doomed the chances for the line—and possibly spelled out a final warning to Bowler and his paper—was the destruction by fire of a part of the Bethel newspaper plant. Following this event, the Bridgton News announced, “Rumford, the big city metropolis, is getting large enough, with the population big cities attract, to be wicked.” The News continued, “The reports of murder, arson and vice of all varieties, indicate that it is keeping up to the requirements!”

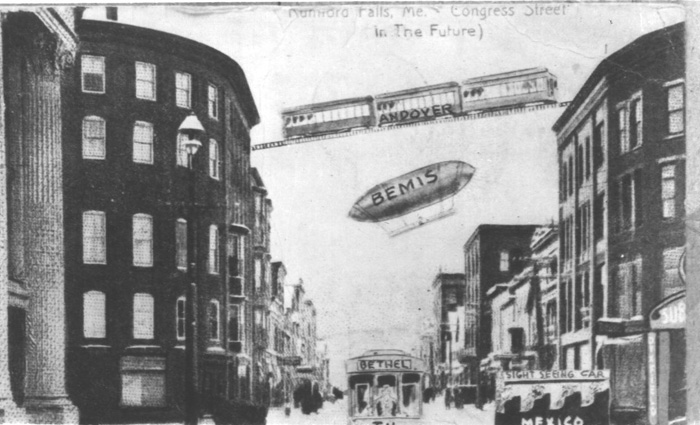

Despite the fact that the fire was a direct blow to Bowler and his adherents, support for the electric railway was still much in evidence during the winter of 1907-08, especially with those living along the proposed route. Yet, Rumford Falls remained a tumultuous pocket of distrust and argument. One of the more interesting byproducts of the controversy appeared in the form of a postcard (see below) of the street railway that soon was advertised as available at one Congress Street store at Rumford Falls. “It shows a car of the proposed railway,” the ad stated, “stalled in front of the store. Then in plain sight is the elevated train from Andover . . . then also there is a flying machine "Bemis" floating majestically above the tops of the blocks.” For many, the railway to Bethel must have seemed nothing but a scheme, but few on either side stood on solid enough ground to accuse the other of deception or fraudulence. And, no doubt, the many benefits the citizens of Rumford did receive through Mr. Chisholm’s benevolence helped in the long term to sway more to his side. It probably came as no surprise, therefore, when, in April of 1908, E. C. Bowler announced that henceforth the Rumford Citizen would attempt to cover more evenly all of Oxford County and in this quest change from a six to a twelve page paper that would be known as The Oxford County Citizen. Most importantly, the paper would move back to Bethel permanently. At least for the moment, the confrontation appeared over.

Rumford’s Congress Street as it might have been

During the next four years The Oxford County Citizen’s pages continued to include Bowler’s hopeful praise of attempts to get the Bethel-Rumford electric railway proposal off the ground. In some of his columns, it was projected to connect onto small lines in Norway, South Paris, Fryeburg, Lovell, Stoneham, or Berlin, New Hampshire, but little action was ever taken.

In Rumford, things were reasonably quiet after 1908 on the railway issue, and few opposing Mr. Chisholm’s activities sought to indicate their sentiments in print. And for Bowler, who left Bethel for Portland in 1912, remaining to fight for the ill-fated railroad meant “standing still would be going backward.” Many years later, writing of his battle with the powerful monopoly at Rumford Falls, Bowler set down the following in his usual facetious style: “This is the History of Oxford County until the period when Hugh J. Chisholm looked upon the Great Falls at Rumford, and said, ‘Let there be power, ten years hence,’ and said to this man, ‘Goeth thou up the River,’ and to another man, ‘Goeth thou down the River and buy ye all the land of whatever sort ye can bargain for. I, Chisholm, will supply the funds wherewith to pay. Yea, there will be Power here, and I will be It!”