Addison Emery Verrill: Eminent Zoologist

Title

Creator

Source

Publisher

Date

Format

Identifier

Text Record

Subjects

Collection

Full Text

Addison Emery Verrill

Eminent Zoologist

by Stanley Russell Howe

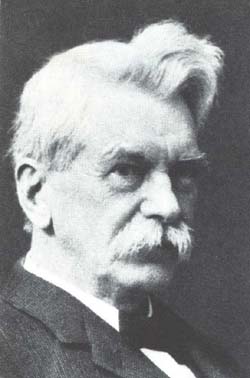

Addison E. Verrill (1839-1926)

One of the most eminent zoologists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Addison Emery Verrill was born on Patch Mountain, Greenwood, Maine, on 9 February 1839, the second son of George Washington and Lucy Hillborn Verrill. He was prepared for college by his own efforts at self education and at the Norway Liberal Institute in Norway, Maine, where his family lived after 1853. Entering Harvard College in 1859, he was an assistant to Louis Agassiz from 1860 to 1864—two years after his graduation from the Lawrence Scientific School with his B.S. degree. As an undergraduate, he spent several summers in field work with Alpheus Hyatt and Nathaniel S. Shaler doing field work in Maine, Labrador, and the islands of Anticosti and Grand Manan. In 1864, he was called to Yale University to become the first professor of zoology in the United States. He remained in the post until his retirement in 1907 as professor emeritus. For fourteen years (1870-1894), he also taught at the Sheffield Scientific School and during two years (1868-1870), he acted as professor of entomology and comparative anatomy at the University of Wisconsin.

On 15 June 1865, Verrill married Flora Louisa Smith of Norway, Maine, sister of his associate Sidney I. Smith. His Report upon the Invertebrate Animal of Vineyard Sound and Adjacent Waters was published in 1873, the first extensive ecological study of the maritime invertebrates of the southern New England coast and for years a standard reference work. For sixteen years (1871-1887), he was in charge of the scientific work of the United States Commission of Fish and Fisheries in southern New England. In this connection, he designed a cradle sieve, a rake dredge, and a rope tangle for collecting starfish in oyster beds. His scientific studies were interrupted for several years by his work in preparing zoological definitions for the revised edition of Webster’s International Dictionary (1890). During the ensuing years, he investigated the invertebrate life of the northern New England coast, the Gulf Stream, Pacific Coast of Central America, the Bermudas, and the West Indies. Everywhere he turned, his discerning eyes found new types of animal life which others had overlooked. He once estimated, for example, that he had discovered over a thousand undescribed forms. Much of his most important work appeared after his retirement in 1907 at the age of sixty eight. When he was eighty five and still vigorous, he extended his studies to the Hawaiian Islands, and during the next two years discovered many new species. Shortly after this time, his health declined at the end of his eighty eighth year, and he died at Santa Barbara, California, survived by four of his six children.

Over a period of more than sixty years, Addison Verrill's publications covered a wide range of subjects, but the majority dealt with marine invertebrates—among them sponges, corals, sea-stars, worms, mollusks and representatives of other groups. In addition to his noteworthy achievements in the classification of marine invertebrates, he built up a large zoological collection in the Peabody Museum at Yale, of which he was the curator for over forty years (1867-1910) and served as the editor of the American Journal of Science for more than fifty years (1869-1920). He was an early member of the National Academy of Sciences and of a number of other American and foreign learned societies. For several years, he was president of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Tall, with thick, wavy hair, and piercing blue eyes, he is recalled as a man with an impressive memory, an encyclopedic mind, and an uncanny aptitude for close discrimination. He possessed great skill in drawing, producing with little apparent effort detailed sketches of the most intricate structures of numerous organisms. In contrast to some of his contemporaries, he was ever the patient and painstaking investigator, fully capable of providing an impressive number of details with remarkable clarity and order. He was never satisfied with obtaining his knowledge of animals under purely laboratory conditions alone, but ventured forth in many parts of the world to view specimens in their natural settings.

From an article in the Oxford County Advertiser for 24 July 1914, it can be determined that he began his scientific researches early in life.[1] While living in Norway as a student (1853-55), he made collections of Maine minerals, insects, plants, mammals, birds, and reptiles. During his explorations in the hills of Oxford County, he discovered and identified a number of rare minerals not before known in Maine, including tin ore at Paris, zircon and corundum in Greenwood, chrysoberyl in large crystals in Norway and Amazon stones in Waterford. A little later, in 1859, he added several species of flowering plants to the flora of the United States as recorded in Gray’s Botany. His catalog of the birds of Norway, published in 1862, was the first general list of birds of Maine.

In the Oxford County Advertiser for 7 August 1914, Verrill recalled his years living in Greenwood City from 1845 to 1853, except for one year (1852) when he resided in Locke’s Mills. He remembered that during this time there were “two stores, two taverns with large stables, etc., about six dwelling houses, a saw mill (in ruins after 1849), a grist mill, a shingle mill, a school house and a church.” The entire village except for the church, which stood a little north of the rest of the village, was destroyed by fire in May 1862.

Described by the Dictionary of American Biography as “one of the greatest systematic zoologists of America,” Addison Emery Verrill had so few students following his appointment in 1864 that he taught historical physical geology from 1870 to 1894. As one observer noted, it was “unfortunate” that such an “able investigator” as Verrill was “burdened” with “so much routine teaching.” Nevertheless, Verrill’s enthusiasm for making scientific discoveries and meticulously recording them continued throughout the entire span of his life, beginning with youth and extending to advanced old age. So, from Patch Mountain to Yale and on to many parts of the world, Addison E. Verrill made his mark on the larger world. Brooks Mather Kelley, in his Yale: A History (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1974), considers Verrill as “by far the most important” of the noteworthy scientists appointed during the latter half of the 19th century at Yale.

[1] Verrill’s articles for the Advertiser are collected in the book, Addison Verrill’s Greenwood, edited by Larry Glatz and Herbert Adams and published in 2016 by the Bethel Historical Society and Greenwood Historical Society. Copies of this book may be purchased at our museum shop or online store.