The following

material is excerpted from an exhibit that was on display at the

Bethel Historical Society from June 2, 2007, through September 9, 2011

Bethel Historical Society from June 2, 2007, through September 9, 2011

Introduction

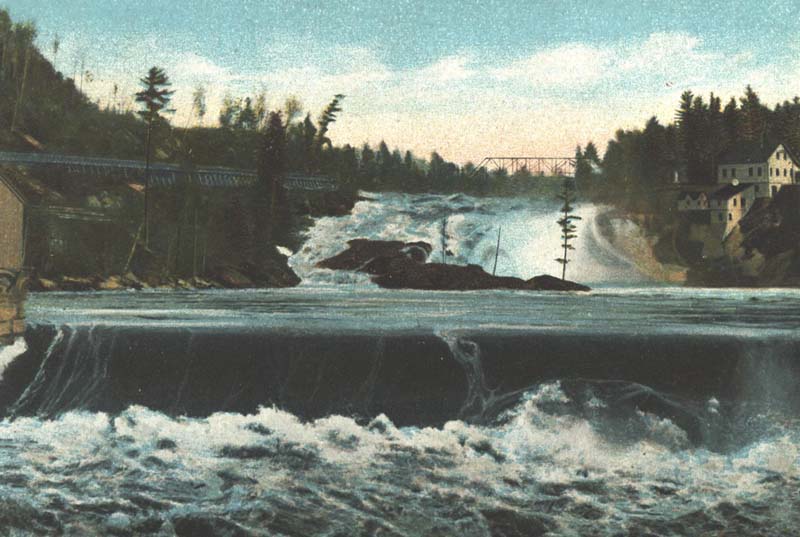

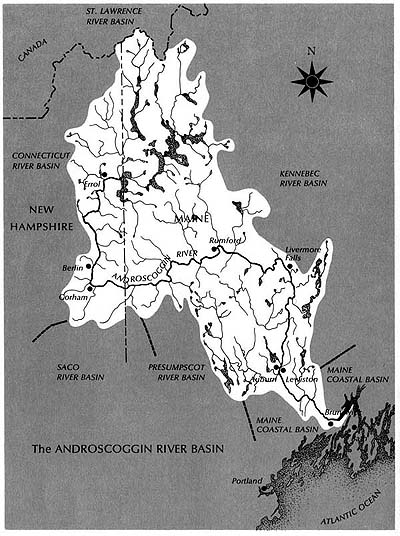

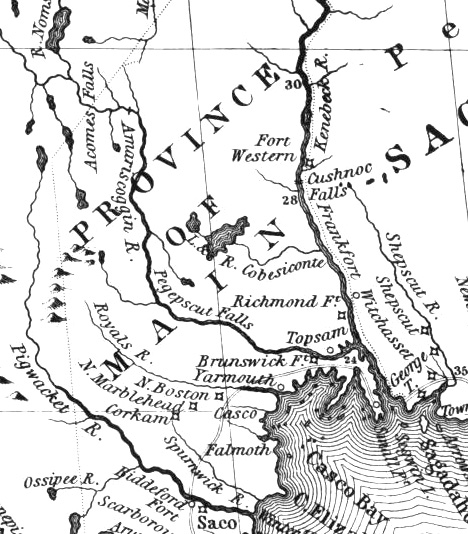

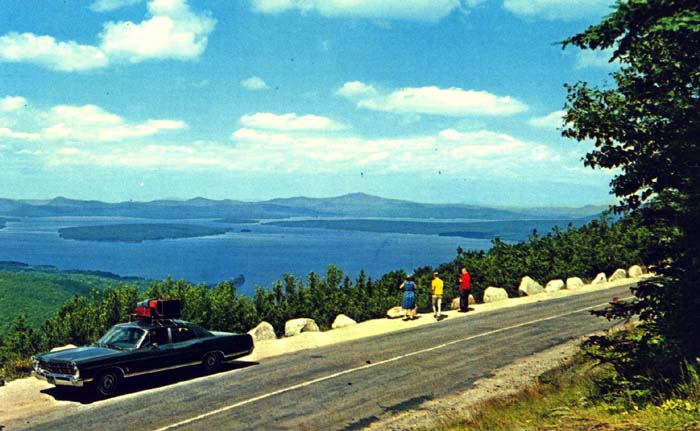

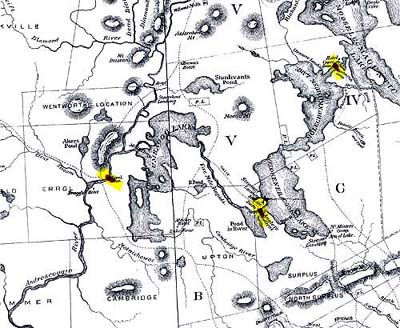

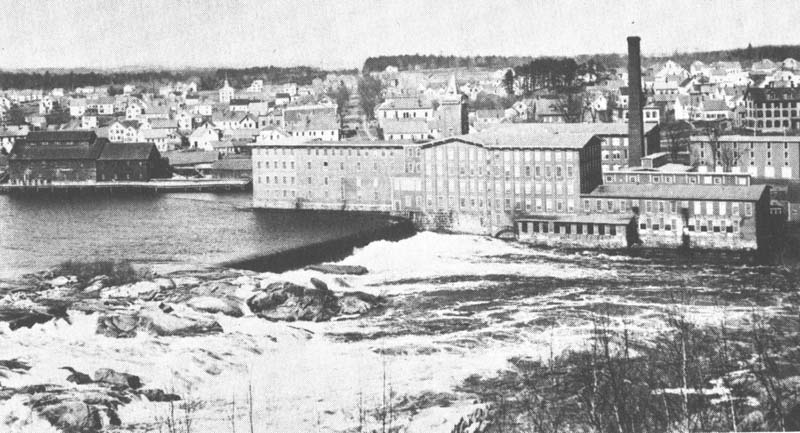

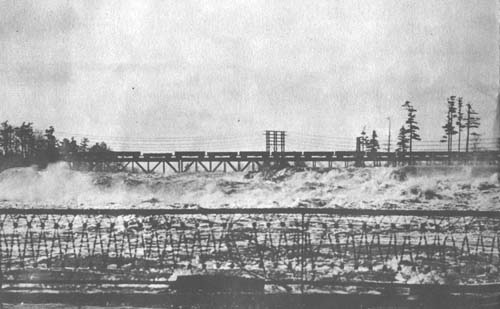

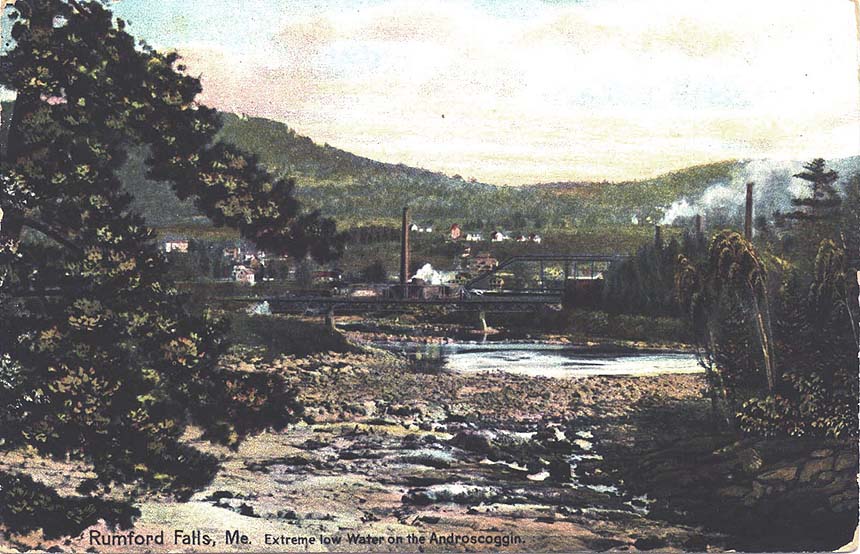

IntroductionOne of the largest rivers in New England and the third largest in Maine, the Androscoggin drains an area of over 3,400 square miles in Maine and New Hampshire. The 170-mile waterway begins its journey near Errol, New Hampshire, where the outlet to the Rangeley Lakes and the Magalloway River join, and—punctuated with numerous rapids and impressive waterfalls (including that at Rumford, shown at left)—eventually mingles with the waters of the Kennebec River in Merrymeeting Bay below Brunswick, Maine, before flowing into the Atlantic. Long used by a variety of industries to power machinery and to carry industrial and municipal waste products downstream, the Androscoggin was one of the ten most polluted rivers in the United States by the 1960s. However, discharge regulations set by the 1948 Water Pollution Control Act and its subsequent amendments have allowed the River to make a comeback, so that in some sections (notably upriver of Jay, Maine), it is becoming a significant recreational resource for communities along its banks.

The Androscoggin River has both supported and constrained human activities along its course over a period of many centuries. Consequently, this exhibit draws attention to the ways the Androscoggin has affected the lives of people on and around it—and how those same people have affected the Androscoggin during the river’s journey through time. Through the use of selected images, artifacts and text, this display presents a vivid picture of the Androscoggin's past: as a transportation route for Native Americans and, during more recent periods, a watercourse for the movement of logs destined for lumber and paper mills; as a source of nutrients for agricultural production and waterpower for industry; as a conveyor of a variety of pollutants to the cold waters of the Atlantic; and as a popular destination for boaters, fishermen, artists, photographers, and nature enthusiasts.

The 3,400 square miles that make up the Androscoggin basin—the river and its surrounding watershed—were formed over millions of years, with the landscape we see today bearing the marks of the closing stages of the last ice age, which ended some 12-15,000 years ago. The geologic theory behind the formation of the Androscoggin River valley therefore has much to do with the melting and retreat of the great glaciers that once covered northern New England with a mile-thick coating of ice. According to one theory, the retreating glaciers left a chain of lakes from the Maine coast near Brunswick to the Canadian border where present-day New Hampshire and Maine meet. Erosion from higher elevations caused many of the smaller lakes to fill up with sediment; eventually, a river channel formed in these formerly wide but shallow water bodies, leaving behind broad areas of rich alluvial soil in the bottom lands—called “intervales” by New Englanders. Today, many of these low lying intervales along the Androscoggin contain some of the best farmland remaining in western and southern Maine.

A River’s Journey to the Sea

The

northernmost sources of the Androscoggin lie nearly 3,500 feet up on

the sides of the Border Mountains on the international boundary between

the United States and Canada. However, the Androscoggin, proper,

starts at the confluence of the outflow stream from Umbagog Lake—the

lowest of several vast bodies of water in the Rangeley Lakes chain—and

the Magalloway River, whose several branches extend far to the

north. Here, at an elevation of some 1200 feet above sea level in

northeastern New Hampshire, the Androscoggin passes through Errol Dam

(one of over twenty flood-control or hydropower dams on the waterway)

and then through the famous “Thirteen Mile Woods,” a winding,

relatively calm stretch of water whose heavily forested shorelines are

now protected by conservation easements. Entering the Pontook

Basin, the river valley broadens, with pastures and cultivated land

much in evidence. After several miles of “fast water,” the River

approaches the City of Berlin, where it drops nearly three hundred feet

in a distance of about two miles—what many have referred to as the

“real upper falls of the Androscoggin River.” At Gorham, the next

town downriver, the Androscoggin turns eastward from its southerly

course and runs another twenty miles past some of the highest peaks in

the Appalachian Mountains—crossing the state line into Maine—to the

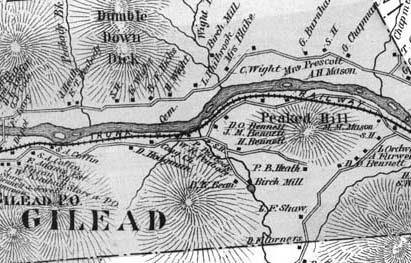

town of Bethel.Near Bethel, the Androscoggin widens and turns northeasterly as several smaller rivers, including the Wild, Sunday, and Bear, add their waters to the mixture. A very gradual drop in elevation occurs between Bethel and Rumford, where the Androscoggin makes one of the most spectacular leaps along its course, dropping over 170 feet in three falls spread out over a mile. Making a U-turn and heading southeast again, the River passes between the towns of Dixfield and Peru, where, at an elevation of 416 feet above the sea, the Webb River enters from the north. Mountains of lower elevation than those at the Maine/New Hampshire border combine with intervales to produce a scene that is now more pastoral than primitive. At the huge intervale of Canton Point, once one of the largest plots cultivated by Native Americans in New England, the Androscoggin makes a sharp turn and flows through Jay and Livermore Falls, two industrial towns built where the River drops over several major waterfalls.

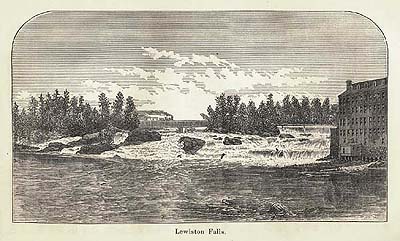

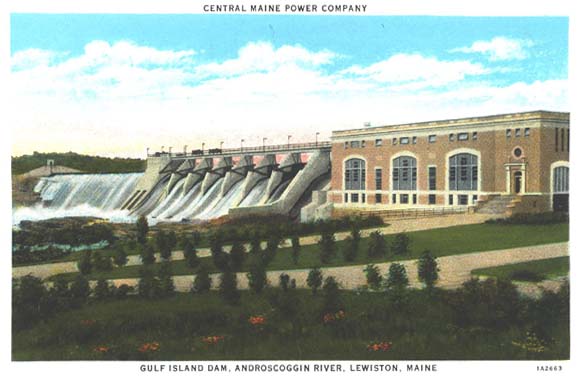

Below Livermore Falls, the Androscoggin valley widens considerably and the River’s downward flow become more gradual. Below the towns of Leeds and Turner, the River enters a man-made lake created when Gulf Island Dam—the last major dam built on the Androscoggin—was constructed in the mid-1920s. For the next dozen miles, the River flows between the twin cities of Auburn and Lewiston. Just before reaching the “Great Falls,” much of the Androscoggin is diverted by canal through Lewiston, once a bustling center of textile manufacturing. After receiving the waters of the Little Androscoggin at Auburn, the Androscoggin continues its journey to the next series of rapids at Lisbon Falls. Four miles beyond the bottom of Lisbon Falls Rapids, the River enters Brunswick, the oldest town in the valley. After swinging to the east and dropping over a final series of falls, the Androscoggin flows onward for another six miles until it empties into Merrymeeting Bay. Here, the waters of the Androscoggin (said to average 4.19 billion gallons entering the Bay each day) mix with those of the Kennebec and travel seventeen miles due south, past the City of Bath, until finally flowing into Atlantic where the ill-fated Popham Colony was established as New England’s first English Colony in 1607.

Major

Rivers and Streams in the Androscoggin Watershed

Alder

River, Bear River, Black Brook, Clear Stream, Concord River, Cupsuptic

River, Dead Cambridge River, Dead Diamond River, Dead River, Ellis

River, Kennebago River, Little Androscoggin River, Little River,

Magalloway River, Martin Stream, Nezinscot River, Peabody River,

Pleasant River, Rangeley River, Rapid River, Sabattus River, Sawyer

Brook, Seven Mile Stream, Sunday River, Swift River, Swift Cambridge

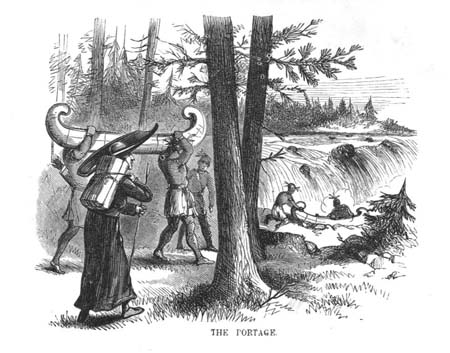

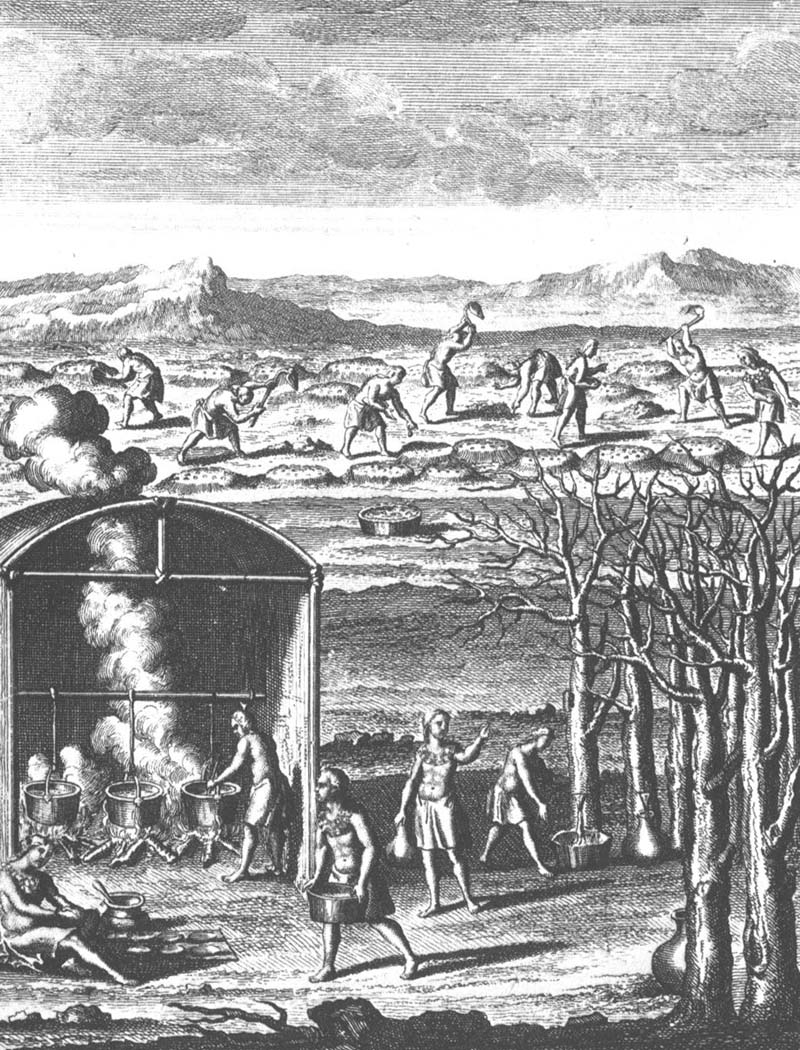

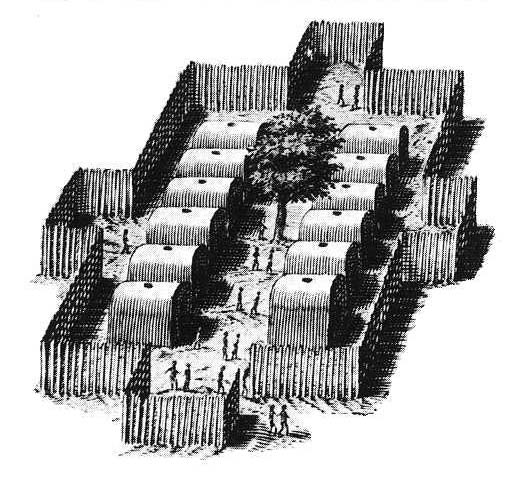

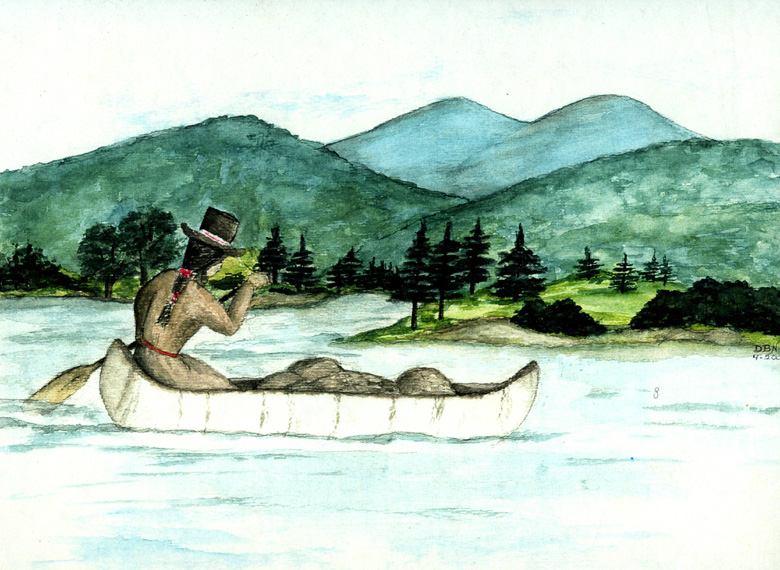

River, Swift Diamond River, Webb River, Wild RiverNative Americans lived alongside, and traveled on, the Androscoggin River centuries before the first Europeans explored the coast of Maine, an effort that may have begun as early as the 1490s. Moving up the Androscoggin valley after the glaciers retreated over 12,000 years ago, the ancestors of today’s Abenaki Indians—the “dawn land” people—survived by hunting large game, especially caribou. Termed the “Paleo-Indians” by some scholars, these inhabitants of the valley erected a stone structure for the storage of meat, dated to 11,120 years before the present (and now on display at the Maine State Museum), at the “Vail Site” on the old course of the Magalloway River—a northern tributary to the Androscoggin. Many other prehistoric Indian encampment sites along the Androscoggin, notably on points of land jutting into the river (for example, “Powwow Point” at Bethel) and on raised elevations not far from the water’s edge, have been identified and documented through archaeological investigations carried out by the Maine Historic Preservation Commission and Maine State Museum. Such investigations have aided in the reconstruction of the lifestyles of the original human inhabitants who occupied the Androscoggin watershed.

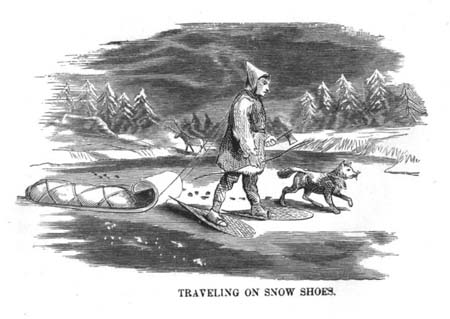

It is difficult to make a reliable estimate of local Abenaki populations around 1600, when Europeans first ventured up the Kennebec into Merrymeeting Bay and then up the “Pejepscot”—a term then used to label the lowest section of the Androscoggin—but at least several hundred native people inhabited the Androscoggin watershed (out of some 100,000 in New England) at that time. Interrelated through marriage, and sharing a common dialect, these Indians had long participated in an annual cycle of migration that took them to seashore camps in the summer, to deep woods hunting camps in the winter, and back to their riverside villages for late fall feasting and spring fishing and planting. Known today as the “Amarascoggins,” this Abenaki group has long been erroneously identified by the term “Anasagunticooks,” a name associated with the missionary village of St. Francis (Odanak), near the St. Lawrence River in Canada’s Québec Province, and to those Indians—mainly Abenaki in ethnic origin—who resided there and traveled up and down the Androscoggin valley after 1700.

Throughout the 17th and during the first half of the 18th century, ongoing frontier warfare between French Canadian colonists in the St. Lawrence Valley and Protestant New Englanders moving north up Maine’s river systems placed the Androscoggin valley Abenaki in an awkward (and dangerous) position; forced to choose sides, many of these Indians retreated to mission villages in Canada where they stayed between seasonal hunting and fishing forays in their old territories to the south. Following the loss of Canada in 1763, English settlements spread further up the valley in relative security. Some of the Indians who had withdrawn to Canada, including the so-called “Anasagunticooks” (see above), returned to the Androscoggin valley where they interacted with the white settlers in a spirit of accommodation. Anxious to remain in their ancient homelands, these individuals were tested again during the American Revolution, when they found themselves split in allegiance between the colonists and the English. Even after that conflict, a number of Abenaki stayed in the region, assuming the role of guides, craftsmen or advisors to the white newcomers, and, in many instances, becoming absorbed into the white way of life through inter-marriage.

From

“Amascongan” to “Androscoggin”

“The

river

now known as the Androscoggin, and from which the tribe inhabiting its

shores received its names, was variously called the Anasagunticook, the

Anconganunticook, Amasaquanteg, and Amascongan. The latter is the

original of Androscoggin, as appears by the deposition of the Indian

Perepole. The name has been written in some sixty different

forms, as its sound was received by the ancient hunters, owners, and

settlers. There seems to have been a disposition to make it

conform to known words in the English usage. The name “Coggin” is

a family appellation in New England; and it was easy to place before

it, according to each man’s preference, other familiar names, and to

call the stream “Ambrose Coggin,” “Amos Coggin,” “Andrews Coggin,”

“Andros Coggin,” and “Andrus Coggin.” Vetromile says that Coggin

means “coming”; and that Ammascoggin means “fish coming in the spring,”

and that Androscoggin means “Andros coming,” referring to the visit of

a former governor of the province. But the visit of Governor

Andros was not made until 1688, while the river is called Androscoggin

in an indenture, made in 1639, between Thomas Purchase and Governor

Winthrop.”— Wheeler, History of Brunswick, Topsham, and Harpswell, Maine (1878)

A

River of Many Names: Perepole’s Testimony

"I

Perepole of lawful age testify and say that the Indian Name of the

River was Pejepscook from Quabecook what is now called Merrymeeting Bay

up as far as amitgonpontook [New Auburn/Laurel Hill] what the English

call Harrisses falls [“Great Falls” at Auburn/Lewiston] and all the

River from Harrisses falls up was called ammoscongon and the largest

falls on the river was above Rockamecook [Canton Point] about twelve

miles, and them falls [Rumford Falls] have got three pitches, and there

is no other falls on the River like them and the Indians yused to catch

the most Salmon at the foot of them falls, and the . . . Indians yused

to say when they went down the River from Rockamecook and when they got

down over the falls by Harrises they say now come Pejepscook."— 17th century deposition by Perepole, an Androscoggin valley Abenaki

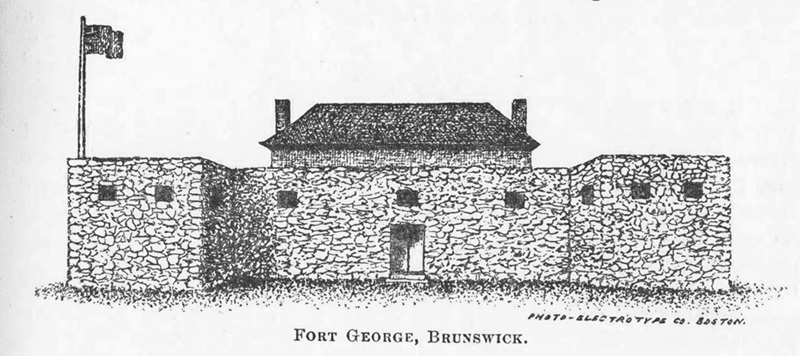

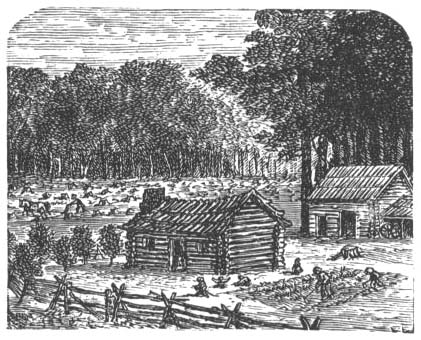

The permanent colonial settlement of the Androscoggin valley began in the 1620s at Brunswick and, not surprisingly, that community became the first incorporated town on the River in 1717. But it was not until the defeat of French Canada by the British in 1763 that the region upriver of “Pejepscot” was considered safe for the development of new towns. Thus it was that the first settlers in such places as Durham, Lewiston, Greene, Turner, Livermore, Dixfield, Rumford, Newry, and Bethel did not arrive until the 1760s and 1770s, just before and during the American Revolution. Although Shelburne, New Hampshire, was settled around 1770, most of the towns between that community and Umbagog Lake were not permanently inhabited by white people until the first quarter of the nineteenth century.

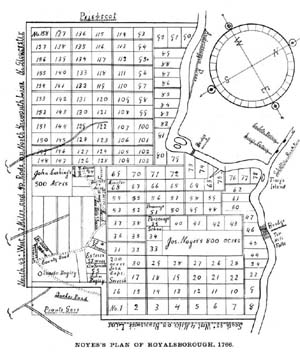

The published histories of these towns indicate that many were granted to people of influence who had little, if any, interest in relocating to the “Androscoggin country,” a term frequently applied to the upper valley in old documents. These absentee landlords, some of whom received grants as payment for military service during the French and Indian wars, hired surveyors to create town plans divided into grid patterns of roughly 50-acre parcels that virtually ignored the local topography—except when it came to the nutrient-rich intervales along the Androscoggin. Anxious to take advantage of the agricultural and forest wealth of this newly-opened territory, the hardy settlers (many of whom were from northern Massachusetts and southwestern New Hampshire) purchased farmsteads from the town proprietors or, in some cases, were given land in an effort to meet certain grant stipulations. It’s worth noting that the migration of people into the middle and upper Androscoggin valley was slowed but not halted by the Revolution, although an August 1781 Indian raid—the last in New England—on the towns of Newry, Bethel, Gilead and Shelburne produced tensions that lasted until the close of the War two years later.

s

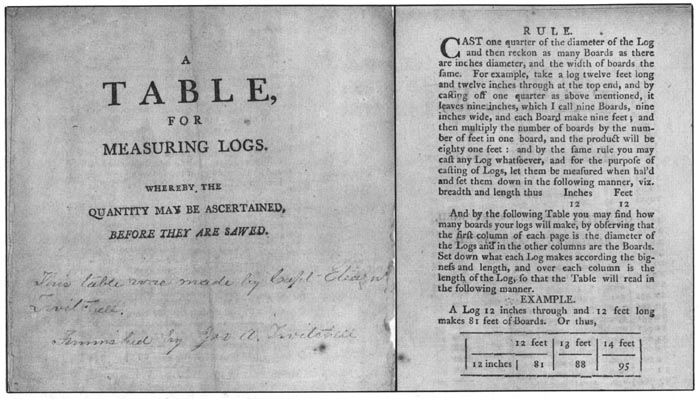

In his 1851 book, Forest Life and Forest Trees, John S. Springer wrote of the abundant manufacturing opportunities on the Androscoggin: “Respecting the water power and privileges on this river, I doubt whether there is a state in the Union that can show so many as we can on the Androscoggin and its tributaries. In the distance of half a mile on the river, at this place (Brunswick), we have [a] forty-one feet fall (three dams across the river), [and] consequently the water may be used in this distance three times. . . . The capacity of the Androscoggin is sufficient for carrying two hundred thousand spindles. . . . All that is requisite to make this river the seat of the most extensive factory operations in the world is capital, and from the superior water power here presented, it is fair to presume that the attention of capitalists may ultimately lead to investments in manufacturing on a magnificent scale.”

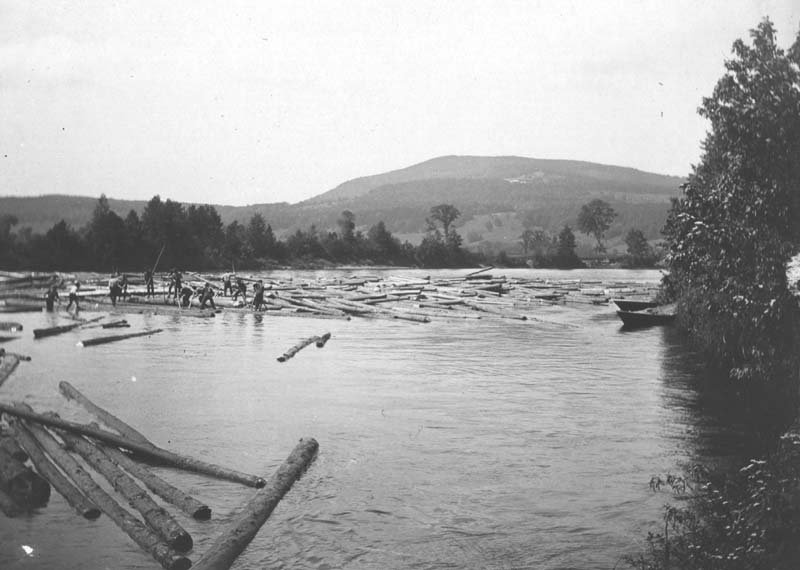

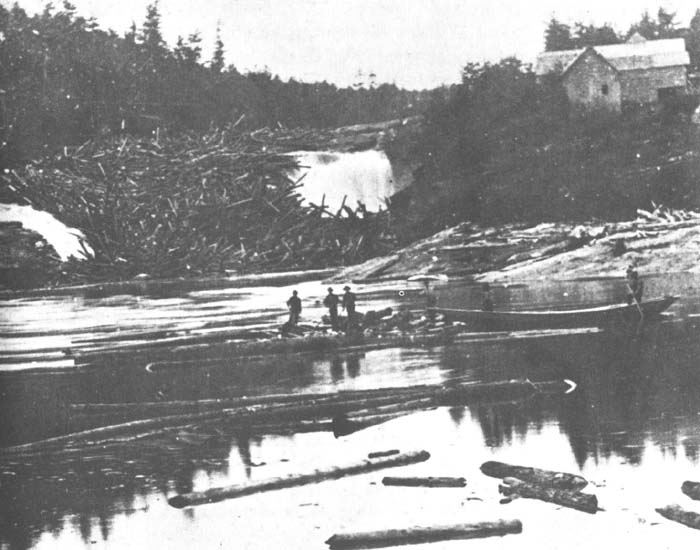

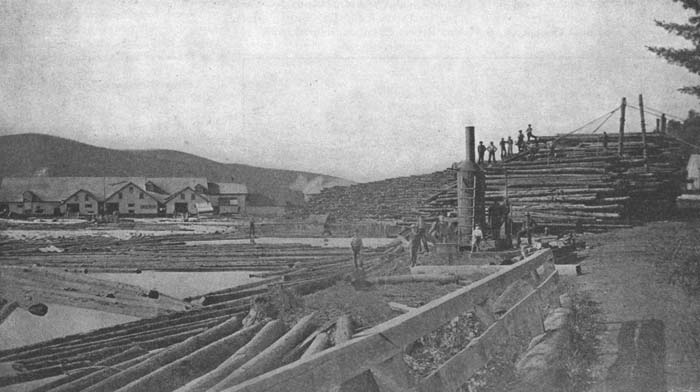

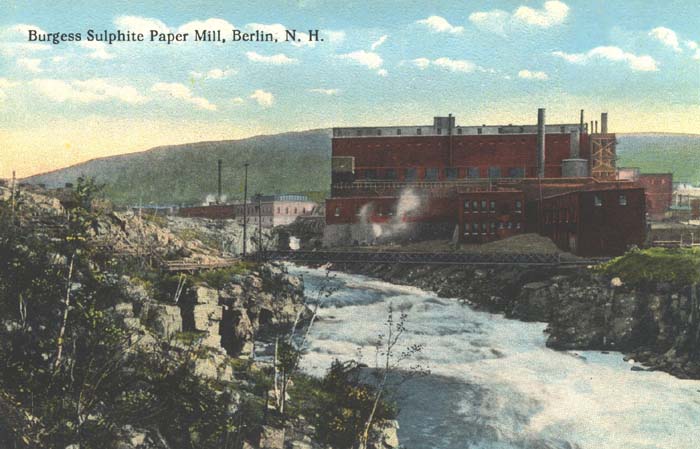

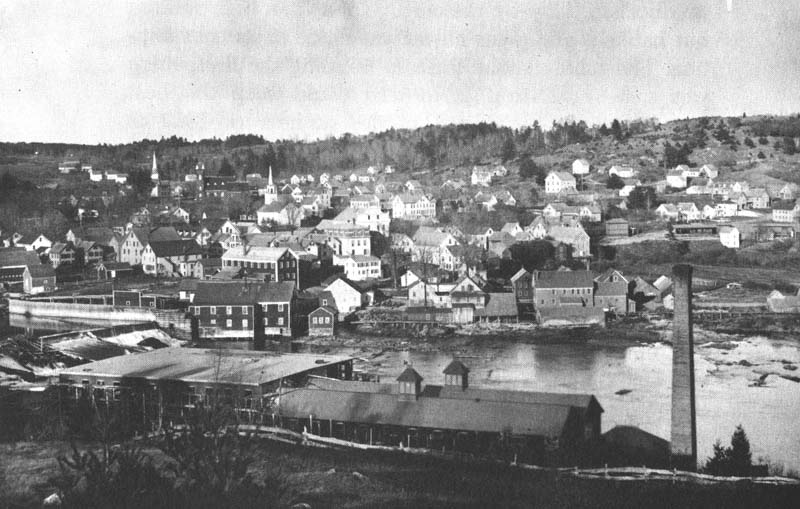

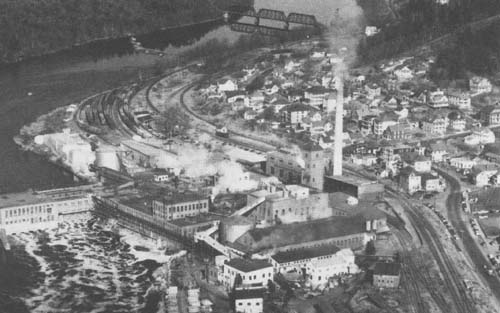

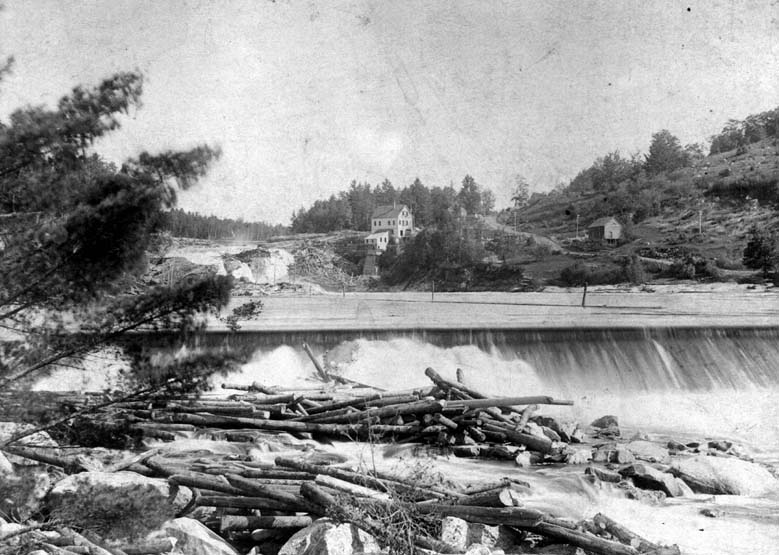

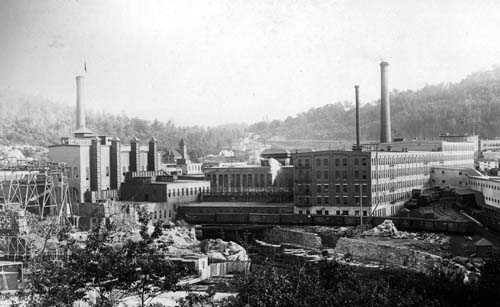

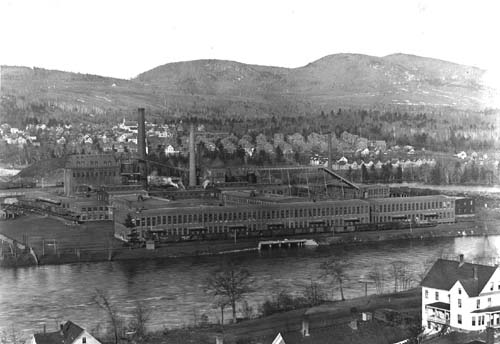

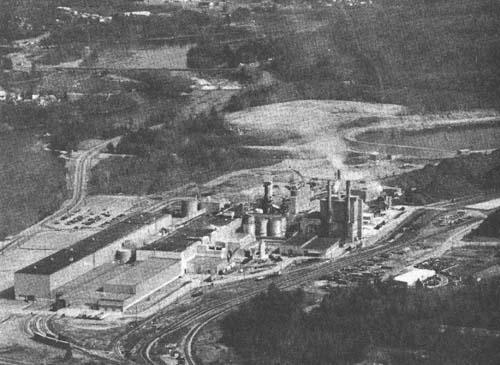

Springer’s predictions came true, for by the end of the 19th century the Androscoggin valley was the site of some of the largest paper-producing companies in the world. But even before the Civil War, the Androscoggin was being extensively employed for industrial purposes. For example, the floating of logs downriver to be converted into lumber had been taking place for decades, with some two to three million board feet “run down” to Brunswick yearly in the decade between 1840 and 1850. Indeed, Brunswick seems to have dominated the lumber business on the middle and lower Androscoggin at this time (much as Bangor did on the Penobscot) for, according to Springer, “there are about sixty saw-mills on this river [Androscoggin] and its tributaries, thirty-two of which are at Brunswick and Topsham. However, by 1852, large lumber mills at Berlin, New Hampshire, were beginning to draw business away from Brunswick. Established by several wealthy Portland businessmen, including John Bundy Brown, J. S. Little, and Hezekiah Wilson, the mills at Berlin had access to a vast source of raw material—as well as the Grand Trunk Railway. This mill complex (later known as the Brown Company) would also evolve into one of the country's major paper-making facilities, but not before becoming the largest lumber producer east of the Mississippi by 1890, with a production of some 150,000 board feet a day.

Before closing his remarks about the Androscoggin, Springer hinted at another manufacturing industry just then emerging in the river valley when he stated, “At Brunswick, a cotton factory, with four thousand six hundred spindles is already in operation.” Although he made no mention of the fact, events were even then being set into motion that would create one largest textile manufacturing centers in the Northeast just a short distance upriver at Lewiston.

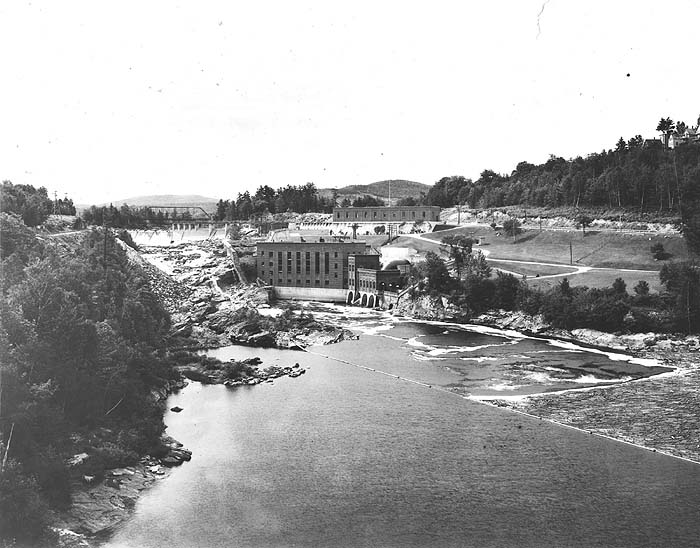

Controlling the Androscoggin: From the

Franklin Company to Florida Light & Power Company

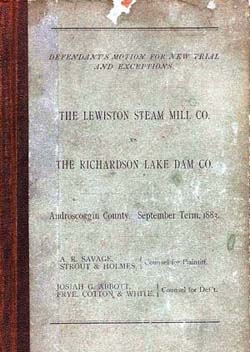

Until the

second quarter of the nineteenth century, the “flowage

rights” (river bottom lands) on the Androscoggin were privately held by

individuals who usually owned the adjacent, or “riparian,” lands along

the waterway. However, with the coming of the great log drives

and the development of textile manufacturing at Lewiston, the need to

construct large dams to control and divert the river’s waters became

essential. As one might expect, loggers and factory owners were

not always in agreement as to when and how much of the Androscoggin’s

flow should be released downriver, a problem that continued even after

large dams were built specifically for electrical generation.The following information from the Souvenir Program of the One Hundredth Anniversary of the City of Lewiston (1895) provides background regarding the longstanding control of the Androscoggin’s flowage rights by the Union Water Power Company (a subsidiary of Central Maine Power Company), which recently divested itself of these rights to Florida Light & Power Company, a national, investor-owned utility company.

“The Great Androscoggin Falls, Dams, Locks and Canal Company was incorporated in 1836 with a capital of $100,000. It was the object of this company to develop the water power at the [Lewiston] ‘Falls.’ . . . In 1837 they procured an engineer who made a survey of the property owned by the company, and executed a plan showing the levels and profiles of different parts of the territory. . . . In 1845, the name was changed to the Lewiston Water Power Company. . . . This company made valuable additions to their real estate, and in 1849 commenced to develop the water power of the place. . . . The stock and property of the company was purchased by the Franklin Company in April, 1857. The Franklin Company was incorporated April 3, 1854, and was organized November 25, 1856, when it took possession of the property of the Water Power Company. . . . The water power privilege and the canals, together with the control of the [Rangeley] lakes, the headwaters of the Androscoggin River, has passed into the possession of the Union Water Power Company, which was organized September 18, 1878, consisting of the Franklin, Bates, Hill, Continental, Androscoggin, and Bleachery Companies.”

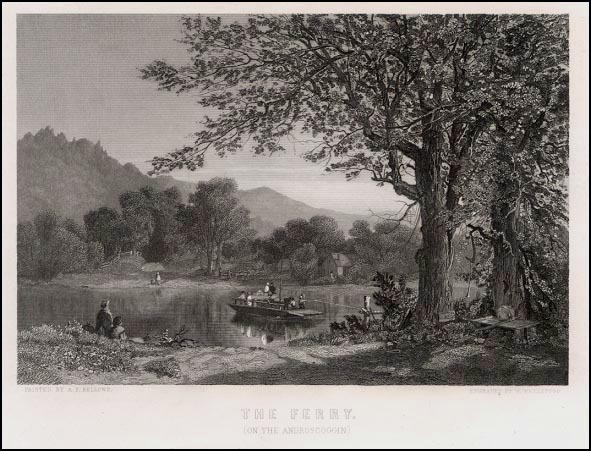

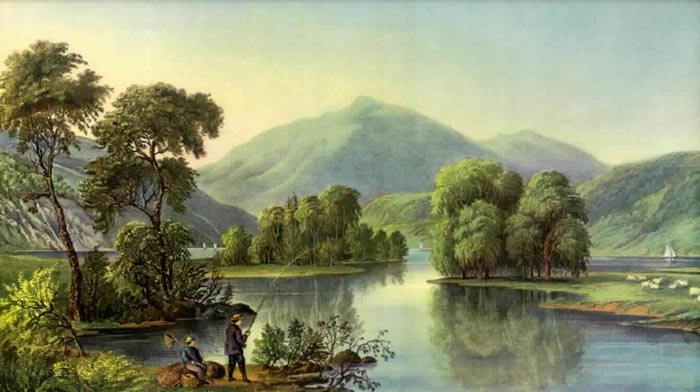

The scenery of the Androscoggin River valley, especially upriver of Rumford Falls where the River flows through a section of the Appalachian Chain of mountains, has inspired painters, photographers, writers and poets for some two centuries.

Regarding the importance of the

Androscoggin valley as a route through the Appalachian Mountains . . .

“The

quickest access to the White Mountain range itself is gained by

the valley of the Androscoggin. This noble river flows by the

extreme

easterly base of that range, where the forms are the most noble and

imposing. Within a very few miles of the foot of Mount

Washington, it

receives the Peabody River, which issues from the narrow Pinkham Pass

between Mount Carter and the White Mountains [Presidential

Range].

This stream is supplied in part from the southeast slopes of the

highest mountains of the chain, and is often swollen into a tremendous

torrent by the storms, or the heavy and sudden showers that drench

their sides. It is the Androscoggin which has engineered [a

place] for

the Grand Trunk Railway, that connects Portland and Montreal, the St.

Lawrence with the Atlantic. That Company are indebted to it for

service in their behalf that was patiently discharged centuries before

Adam.”— Rev. Thomas Starr King, The White Hills: Their Legends, Landscape, and Poetry (1859)

“The Androscoggin is a beautiful river, and the scenery bordering upon it is picturesque and often grand. Persons born and reared upon its banks have an attachment for it which is never weakened in after years, however distant they may wander and whatever may be the lapse of time. Its broad intervales, decorated here and there with drooping elms, rising into table lands with sunny slopes and backed by wooded hills or craggy mountains, make up a succession of vistas which become indelibly stamped upon the memory.”

— William B. Lapham, History of Rumford, Oxford County, Maine (1890)

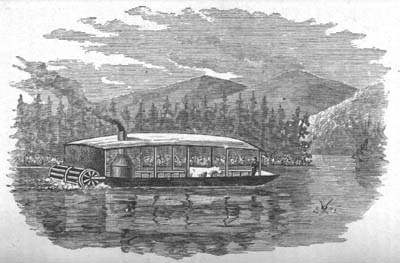

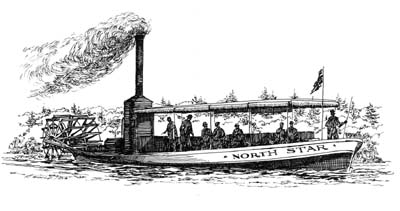

Notwithstanding its many rapids and waterfalls, much of the Androscoggin is navigable, especially by small boats or those with a shallow draft. Canoeing, of course, has been taking place on the river and its tributaries for many centuries, but a handful of steamboats have also plied these waters (for information on some of these steamers, please visit the Courier page on our website at www.bethelhistorical.org). Besides the local vessels featured on this panel, several other steamers have traveled over the surface of the Androscoggin—including ones used solely on the lower river as early as 1819 and as late as 1855 (the eighty-foot long “Victor” was launched that year at Topsham). On rare occasions, even larger craft have been seen on the river; according to a 1970 history of Lisbon, Maine, “About the year 1802, a vessel of sixty-three tons was built at Lisbon by a Captain Woodward and launched into the river during high water, and brought down the river as far as the booms above the upper dam in Brunswick. Here she was taken out of the water and hauled on rollers through the woods to what is now McKeen Street, then down Main Street to the Cove where she was again launched into the river and remained in service for about twenty-five years. . . . One-hundred oxen were employed in hauling the vessel over land.”

No

“Surprise”?

According

to the Oxford Democrat, a

weekly western Maine newspaper, the "Androscoggin Steam Navigation

Company" was incorporated in 1853 and was to have exclusive navigation

rights from Canton Point to Rumford Falls for a twenty-five year

period. The Company issued a capital of $50,000 and secured Hiram

Ricker of Poland Spring to support construction of the side-wheeler

"The Surprise." As the paper reported it, on its maiden voyage,

the vessel nearly capsized when its machinery failed. Living up

to its name, the steamer was soon thereafter taken apart and its engine

used to power a nearby mill. Needless to say, the company's

stockholders must have suffered greatly.

Androscoggin Canal Schemes

“In its

total length of about 175 miles, the river descends 1,245 feet—more

than any other Maine river. The Androscoggin, as Walter Wells

said in 1869, “is a water-power river its whole length, especially from

Rumford Falls to Brunswick. It is navigable only from

Merrymeeting Bay to the foot of Brunswick Falls, and there only for

small craft. When President Timothy Dwight of Yale visited Maine

in 1807, he wrote that the commerce of Brunswick was connected to the

Kennebec River by means of the Androscoggin, which was navigable for

small vessels to within two miles of the falls. . . . Some years

later, Dr. Ezekiel Holmes noted that the Androscoggin had a difficult

and troubled pathway, and had more rapids, falls, and cataracts than

any other river of its size in Maine. Yet Androscoggin valley men

struggled, vainly as it turned out, for the first fifty years of the

nineteenth century to make a waterway of their river.These men included Robert H. Gardiner of Gardiner, Edward Little of Auburn, and F. O. J. Smith of Portland. They and others had surveys made of their favorite schemes by such experienced civil engineers as Colonel Loammi Baldwin and his son Benjamin, both of Middlesex Canal fame; Colonel J. J. Abert of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; Captain James Hall of the Board of Internal Improvements; and Land Agent Noah Barker.

The earliest planning involved the lower river and the challenge posed by the high falls at Brunswick. Two later schemes related to the middle river and involved bypassing the falls at both Lewiston and Brunswick. The upper river inspired three amazing proposals: one to connect the Androscoggin and Connecticut rivers, another to connect the Androscoggin [at Bethel] with Portland by way of the Cumberland and Oxford Canal, and one to make an artificial outlet in [Lower] Richardson Lake to connect it directly with the Androscoggin—bypassing the river’s sixty-five-mile loop through New Hampshire.

None of these schemes matured into construction [and] all attempts to canal, supplement or otherwise adapt the Androscoggin for transportation failed. In general, the failures must be charged to the number, height, and length of the falls, which were excellent for waterpower and industry but impossible for boating.”

— Hayden L. V. Anderson, Canals and Inland Waterways of Maine (1982)

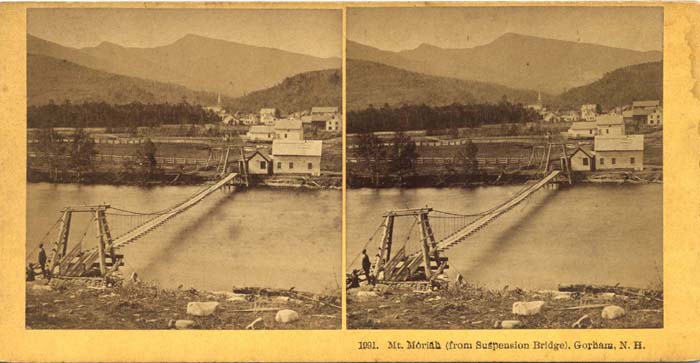

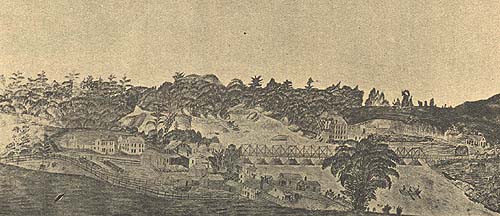

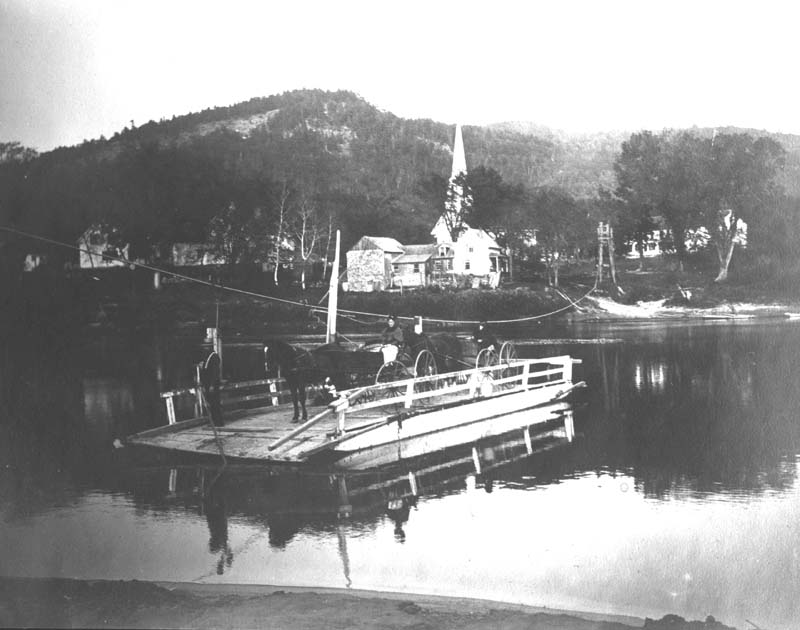

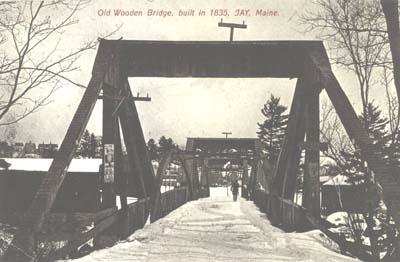

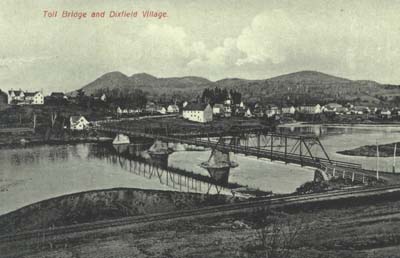

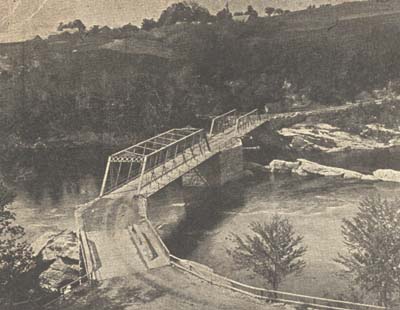

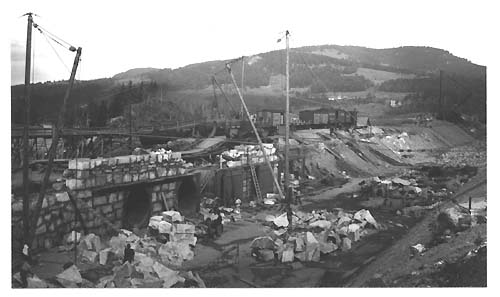

Whether built of wood, stone, metal or concrete, bridges over the Androscoggin have long served as vital links between communities separated by the river, or, in the case of Bethel and other towns, connectors between small villages and neighborhoods. The images offered here give an idea of the various types of bridges erected over the Androscoggin since the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

The development of paper manufacturing on the Androscoggin, and the earliest contamination of the river caused by that type of industry, occurred at the Topsham-Brunswick end of the river only a short time after the Civil War. There, in 1868, the Pejepscot Paper Company was established in an imposing Italianate brick structure built high atop a granite ledge on the Topsham side, just below the bridge connecting the two towns. Speaking of this period in the history of the valley, Page Helm Jones wrote the following in his 1975 work, Evolution of a Valley: The Androscoggin Story:

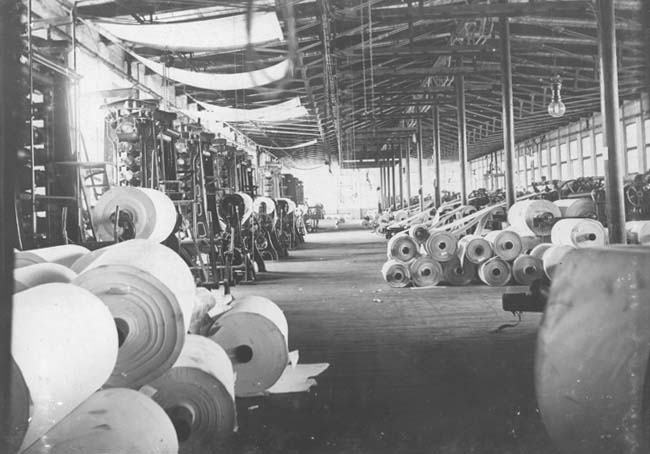

“In 1870 the manufacture of paper was done almost entirely with rags, with some admixture of straw and mechanically ground wood. . . . The industry was seeking improvements in pulp, particularly the desired uniformity and possible lower cost which was improbable with rags. By 1881, a few groundwood plants had been started in the East, and in that year the first one was built by the Umbagog Paper Company at Livermore Falls . . . of which Hugh J. Chisholm of Portland was the moving spirit. This man was to become, with W. W. Brown [of Berlin], the second of the two most influential figures in the economic development of the Upper Androscoggin Valley. . . . This was not only the beginning of a new era in the economy of the valley, but the start of serious industrial river pollution which increased yearly for half a century before public outcry against its continual worsening caused . . . action for the recovery of the river to its former usefulness as a thing of beauty and utility, rather than the vile, lifeless, stinking sewer which it became in the 1940s. Unfortunately, the sulfite process of pulping, which was a godsend to the paper industry, created useless waste liquors laden with oxygen-devouring chemicals and insoluble sediment which gradually covered the river bottom, destroying the water vegetation which is so necessary to water life and to the natural ‘self purification’ which the mill operators said would take care of their sewage.”

“If the mean volume of water that can, in the present state of its reservoirs, be commanded on the river, in the low run of summer, from Rumford falls to the tide, be assumed to be 75,000 cubic feet per minute, for eleven hours a day, the total power of this section of the river is 85,200 horse-power, gross measurement, for the hours specified, or 3,747,600 spindles. What proportion of this power can be economically appropriated, it is not possible now to determine; the proportion is, however, unquestionably unusually large, owing to the favorable conditions of the bottom and banks, and the advantageous character of the falls and rapids with reference to improvement. Not an eighth part of it is now used.

The water-power of this river from the tide to Jay inclusive, is already furnished with excellent railroad communication close at hand, and from Bethel to the State line the Grand Trunk follows the immediate bank of the river. Indeed, no portion of the river below the State line is far removed from railroads. It is navigable to the foot of the lowest falls, for small craft, for about two-thirds the year.”

— Walter Wells, The Water-Power of Maine (1869)

Numerous floods on the Androscoggin have been commonplace over the centuries. In more recent times, the construction of dams to control the river’s flow during periods of high water has been of tremendous aid to those residing or working near the waterway. Nevertheless, the 1987 freshet caused much damage in parts of the river valley, notably in the town of Canton, which, after a detailed study by FEMA, has decided to relocate a number of structures in its main village to higher ground.

“The watershed of the Androscoggin, consisting largely of steep and barren mountains, including the easterly slopes of some of the White Hills, is such as to cause the volume of water in the river to increase very rapidly during severe rainstorms and spring freshets, the rise often amounting to one foot per hour for several successive hours, the banks soon becoming overflowed and the broad intervales presenting the appearance of a raging flood.”

— William B. Lapham, History of Bethel, Formerly Sudbury Canada, Oxford County, Maine (1891)

Major Floods on the Androscoggin River

1723 —

The earliest recorded “freshet” on the Androscoggin occurred in

February. The river was “open not only below but even to the

falls thirty miles above Pejepscot” (Brunswick/Topsham).1784 — In the autumn of this year, high water lifted the barn of Andrew and John Dunning, of Brunswick, off its site on the intervale and carried it intact until it reached the falls.

1785 — In October, “the greatest freshet ever yet recorded on the Androscoggin River” damaged or destroyed many low-lying houses and farmstead from Bethel to Brunswick.

1826 — On August 30, “the most unexpected and rapid rise of water in the Androscoggin occurred that had ever been known. In Livermore and Jay the water rose eight feet in one night.” A number of mills were damaged and ferries swept downstream.

1839 — A February “ice freshet” carried away dams, log booms and mills on the river. The open-truss pier bridges at Bethel and Rumford Point were also destroyed and replaced with ferries the following year.

1869 — In the “Pumpkin Freshet” of October 5, thousands of pumpkins were carried into the Androscoggin River via its tributaries, creating a sight long remembered by valley residents.

1896 — A March flood forced thick cakes of river ice over roads and against bridges, causing much damage. Railroad tracks near the river were undermined and telephone lines in the Bethel area brought down.

1927 — Several days of torrential rain during November resulted in high water along major waterways in Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont. Damage and loss of life was greatest in the latter state.

1936 — Heavy rains in mid-March combined with spring snow melt to produce what has been called “Maine’s greatest flood.” Considerable property damage occurred throughout the Androscoggin valley.

1953 — Despite record runoff, the late March 1953 flood caused less damage than in 1936 due to the absence of ice jams and moving ice. “The discharge of the Androscoggin at Auburn was the second largest since 1850 and probably since 1785.”

1981 — Rains lasting several days in February caused the Androscoggin to overflow its banks, resulting in numerous ice jams on the narrower sections of the upper river.

1987 — On April 1, the worst flooding in Maine in half a century was brought about by melting snows and driving rain. Entire sections of communities along the Androscoggin were cut off as bridges washed out and roads were submerged.

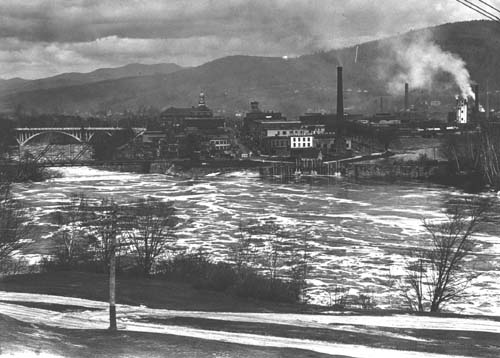

By 1940, many of the mills along the Androscoggin had recovered from the effects of the Depression and were actually increasing production in response to war-time needs. Not surprisingly, these same mills were discharging an extraordinary amount of toxic pollution into the river—as were all of the municipalities along its course. The construction in the late 1920s of the Gulf Island Dam several miles above the Great Falls at Lewiston/Auburn created “Gulf Island Pond,” which backed up the river nearly to Livermore Falls, and worsened the effects of the toxic wastes by drowning the rapids that had naturally provided oxygen to the water. Extremely low water in the river during the winter of 1940-41 brought these appalling conditions to a head, and Lewiston and Auburn residents made an official appeal to the Maine Sanitary Water Board for help. Soon afterward, the firm of Metcalf & Eddy, Engineers, of Boston, was hired to conduct a survey of the Androscoggin, and in February of 1942, they submitted a detailed report that included suggestions for remedial measures to clean up the river. One highly significant outcome of this investigation was the hiring, in 1947, of Dr. Walter Lawrance, Chair of the Chemistry Department at Bates College, as “River Master.” Under his direction, weekly discharge limits were set, and pressure was placed on the paper mills to find a substitute for the sulfite method of pulverizing wood. With the introduction of the kraft pulping process, the tide began to turn, and conditions on the river slowly started to improve.

Although great strides have been made in cleaning up the Androscoggin since the studies of the 1940s were carried out, the middle and lower sections of the river remain seriously impaired when judged against Maine’s other large rivers, including the Saco, Kennebec and Penobscot. As those who cast a line in the Androscoggin today understand only too well, the presence of dioxins and high mercury levels in fish inhabiting these waters is a reminder that more work remains to be done before this great waterway returns to anything resembling its pre-industrial condition.

“New Year’s Day, 1941, ushered in a year which not only would plunge the country into World War II, but would bring to a climax the terrible contamination of one of America’s loveliest rivers. The winter of ’41 began with an unusually scanty snowfall. . . . Snowfall was light and, in addition, there were no less than three winter thaws which took off the scarce snow unseasonably early. When spring came, by the calendar, there was no freshet, no great mass of water rushing down to the sea. The result was that the river was at the lowest level it had been for many a season. Now came the culminating factor: an unusually hot June and July, with little rain. From a faint whiff of hydrogen sulfite which rose from the river in May, the appalling stench of rotten eggs became progressively worse all up and down the river, and reached its climax in the most heavily populated section of Lewiston and Auburn, where roughly sixty thousand indignantly aroused citizens became vocally and politically vehement. It was a community disaster which was not only the topic of all conversation, but caused the slowdown of industry and business in general. Retail stores were deserted and some suffered physically from the effluvia. Jewelers, for example, nearly went berserk keeping their stocks of silverware saleable because the sulfite-laden air turned silver and other metals black overnight. If you were driving from Augusta to Lewiston, you began to smell it at North Monmouth, twenty miles from the city, and it increased in intensity as the road approached the river. Houses painted white turned black and blistered in great ugly patches, and by the time you had reached the city limits, you had to put up your car windows despite the heat and try not to breathe through your nose. It was revolting, and the exodus of families who could afford it became a locust-like invasion of the seashore and the mountain and lakeside camps—provided they were located far from the foul river. The wage earners must of necessity remain, and their outcries reached such a volume that the matter was brought before the newly created Maine Sanitary Water Board. Late in August, that body employed the same firm of Metcalf and Eddy of Boston [who had surveyed the Androscoggin in 1940 for Central Maine Power Company] to conduct a survey of the river and to recommend remedial measures. Thus, out of the despair and suffering of the populace was born the infant movement to recover the river.”

— Page Helm Jones, Evolution of a Valley: The Androscoggin Story (1975)

Photo by Danna B. Nickerson

Photo by Danna B. Nickerson

Photo by Nathan N. Wight

Photo by Nathan N. Wight

The Bethel Historical Society extends its

appreciation to the following individuals and organizations for their assistance in making this exhibition

possible: Androscoggin

Historical Society,

Androscoggin River Alliance,

Androscoggin River Watershed Council, Jay Boschetti, Arlene Greenleaf Brown, Hugh and Linsley Chapman, Tom Fallon, Stanley R. Howe, Robert and Virginia Keniston, Mahoosuc Land Trust, Maine Historic Preservation Commission, George A. Nickerson, Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr., Mary E. Valentine, Nathan N. Wight, John and Susan Wight.