Grafton, Maine: A Historical Sketch

Title

Publisher

Date

Format

Identifier

Full Text

Grafton, Maine: A Historical Sketch

by Margaret Joy Tibbetts

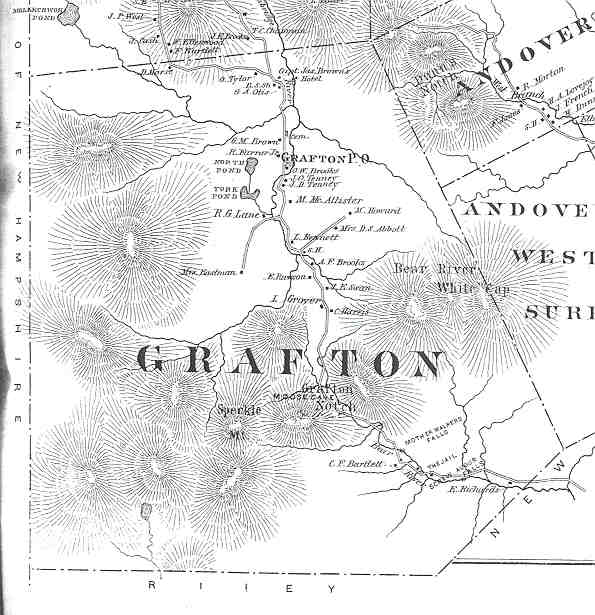

Grafton, from the 1880 Atlas of Oxford County, Maine

The Town of Grafton surrendered its charter in 1919, the year in which I was born. The only buildings in Grafton which I can remember at all belonged to Joe Chapman, who stayed on after the other Grafton citizens moved away. I do remember, however, going through Grafton when I was about five years old and our family accompanied my father (Dr. Raymond R. Tibbetts) on a trip to Upton to see Cedric Judkins. In those days Upton was a substantial journey with a particularly difficult hill just as you approached the town. We stopped for a picnic on the way back before we reached the Notch. The Brown Company had just recently begun the process of reforestation and there were long thick rows of little evergreens, ranging from about three to nine inches high. My father and mother, who had grown up in nineteenth century rural Maine where the forests seemed limitless, could hardly believe that anyone would plant trees, and exclaimed at the Brown Company's foresightedness.

The fate of the Grafton settlement had been determined by the fact that after seventy-five to eighty years of hard cutting most of the easily accessible timber in the town was gone. Without lumber to cut and to sell, the community could not exist. The physical realities of the area precluded much development beyond that of a pioneer logging settlement. A large part of the town was hemmed in between Mt. Speck and Saddleback (which some people call Baldpate) with one major road for access. There were several miles of relatively flat land above the Notch where there was room for farms, but because of the short growing season, farming was of necessity limited; livestock, hay, sometimes potatoes, and grain (usually oats) were the main crops. Frosts came unfailingly in late June and mid-August, and were not unknown in July. The average summer temperature in the warmest month (July) was sixty-six degrees.

Originally, the area later called Grafton was known as Township A. Much of it belonged to out-of-state speculators. In 1830, James Brown of Canton, Maine, made several trips to the area, walking through the Notch on a footpath, the only available road. He is said to have been preceded by Jesse Smith of Newry and his two sons. James Brown's purpose was to look for lumber. In 1834 he married Ruth Swan of Newry and brought her to a log cabin which he had built in what became Grafton.

Brown bought land and built a dam on the Cambridge River which rises in the Notch and flows north to Lake Umbagog, to the east of the present Route 26. He set up a sawmill there; these buildings were completed by 1838. In 1840, he began to build a barn and by 1842 constructed and furnished a large house of fourteen rooms and five fireplaces, where he lived until his death in 1881. For years, Mrs. Brown cooked for the sizable crews of lumbermen who worked for her husband. Their daughter, Mary, was born in 1839, the first child born in Grafton. She lived there all her life until the last two years (1908-1910), when she spent winters with her daughter in Lewiston.

The Brown house was located in an area above the present Grafton cemetery towards the Upton line. In time, Mary Brown married George Otis who came to work for her father. The Otis house was right across the road from the Brown dwelling. Ernest Angevine, as a boy, lived in Upton and often came to Grafton. He has told me that Route 26 goes directly through the site of the Otis home, so we can visualize the old Grafton road as over slightly to the east of the present road.

Other families soon followed the Brown settlement. Most of them also located above the Notch, although, according to the 1858 wall map of Oxford County, down near the Newry line were four farms. Most of the Grafton homes were near the road. An exception was the Morse homestead off to the west near the Upton line and the Upton road known today as Back Street. The settlers who came worked in logging or in subsistence farming.

The first Grafton town records (now in the Newry Town Office) are sketchy indeed. The Newry town officials believe it is possible that some day other records may surface, since not all of the records were turned over when Grafton was dissolved as a town (various local families had records in their possession). By 1852 there were enough residents for Grafton to be incorporated as a town. Reportedly, James Brown's mother, Hannah, chose the name Grafton, perhaps because Grafton, Massachusetts, is located beside Upton, Massachusetts. Most of the early town business dealt with schools and roads.

By 1854 there were nine scholars, thirty by 1856, and thirty-seven by 1859. The numbers did not increase beyond this point and times were lower. There were originally three school districts; houses were widely scattered and even Grafton children could walk only a certain distance to and from school. Originally, schools were held in private homes. Eventually, a schoolhouse was built just above the Notch, according to the Grafton map of 1858. In 1854 the appropriation for schools was $80. Most of the children probably attended the school in the schoolhouse on the Grafton flats, but probably school continued in private homes for the children who lived below the Notch. By the 1880s it would appear from the correspondents for the Norway and Paris papers that almost all of the children were together at the schoolhouse. During the worst of the winter weather there was no school; instead, children had a term in the summer. Obviously the school was a matter of intense interest and there are frequent items in the newspapers about teachers, occasional new textbooks, recitations, etc. A good number of children proportionate to the population went on to school according to news items, usually attending Gould Academy or Andover High School.

Road upkeep was for many years a grievous problem with some improvement coming almost at the end of Grafton's existence. Contact with the world depended on the road through the Notch. Reading the correspondents' reports emphasizes the problem of Grafton's isolation -- economically and psychologically. Travelers faced deep snows in winter, possible floods in spring and fall, and the terrible torture of driving unpaved roads when the frost was coming out in the spring. For many years, individuals were assigned areas of the road to work on, and it is easy to imagine that some areas were better tended than others. At best, the roads were primitive and narrow. Today, by Mother Walker's Falls, on the right of Route 26 as one faces north, one can see a small section of early road together with the small bridges, without rails. It must have been frightful in times of flooding. Throughout the years, correspondents wrote often about road conditions, delay of the stage, no mail for several days and bridges out, while the stage driver was forced to leave the road and at times walk or snowshoe for miles leading his horse. In the Oxford County Advertiser of February 27, 1885, for example, appeared the following: "We are having very bad roads up this way, so bad the Stage had to leave the main road and take the R. Davis logging road a short time ago, and when our surveyor, A. J. Brooks, was notified to break out the roads, I heard he sent word back that he was logging this winter, not breaking roads. And then Richmond Davis took his team out of the woods and broke the roads . . . Wednesday, R. Davis and E. Brown had to take their teams out of the woods to break through Grafton Notch."

The period from 1850 to 1880 was for Grafton a period of growth and activity, even though the Town never grew larger than 115, its population in 1880. In 1859 there were twenty-one men between the ages of eighteen and forty-five. Some Grafton men enlisted in the Civil War. The fate of one of them reminds us how bitterly hard life could be in the nineteenth century. Barrett Wriston, wounded in 1862, was sent home from the Union Army; he died walking home on the road between Bethel and Grafton. He left a wife, who died soon after, and three children. The oldest boy enlisted for the $1,000 bounty and wages available; he survived the army, took his money and emigrated to Minnesota where he prospered.

Basically, Grafton was always a very small and primitive pioneer settlement. There was a post office, but never a real store. There was no church; in the summer, ministers came occasionally from Upton or Newry for services in the schoolhouse, and there were occasional evangelical "missionaries" to the men in the lumber camps.

Life centered on logging and farming, with logging the dominant community interest. There were big lumber camps, in some cases containing over a hundred men with almost as many horses. In the spring after the camps closed there were large crews who worked to get the logs down the Cambridge River to Lake Umbagog, where they were sent down the Androscoggin. By late summer various entrepreneurs would be in Grafton making their plans and by November camps would be set up and men arriving from other parts of Maine, New England, and Canada. Year after year, the correspondents noted the arrival of the crews, the plans of various local women to cook for them, the work piling up for the blacksmiths and the provision of hay and oats for the camps by the local farmers. Often there were reports of the amounts planned for cutting that year. For example, on November 20, 1885, "we understand there is to be some five or six millions of feet of timber put in the Cambridge River this winter."

When logging ended for the winter in late March or April, depending on the weather, interest shifted to the river drive, with the height of water always a strong concern; low water meant particular difficulties.

With summer came the easiest time of the year. The stage arrived every day instead of twice a week or even less, and there were many visitors, either former Graftonites who came back to see relatives, or strangers from the city who came for fresh air. (We forget how foul and disease-ridden nineteenth century cities often were.) The local people went blueberrying and raspberrying everywhere; both berries were plentiful and were reportedly picked by the barrel. It was not uncommon to see bears when berrying, which produced such jokes in the paper as "Uncle Joe Bennett met a bear when picking blueberries the other day. He did not say which one picked more berries." There were occasional picnics and socials, always with refreshments. To be sure, sometimes the nights were cold and there were worries about deer in the garden or rotting potatoes, but invariably references were made to beautiful summer days.

In the 1870s tourism was becoming something of an economic factor. Farrar's Illustrated Guidebook of 1879 (see below) describes the trip from Bethel to Upton along lines familiar to many of us except for the time involved; Farrar says that if one leaves Bethel after arrival on the morning train, Upton is reached by early evening. The sights along the way are carefully listed: Poplar Tavern, Screw Auger Falls, the Devil's Horseshoe (a large horseshoe-shaped indentation in the rock above Screw Auger), the Jail (a deep pothole made in stone with sides too high and steep to climb from easily), and Moose Cave. Neither the Devil's Horseshoe nor the Jail are identified for tourists by today's road signs, but our family always visited them in the 1930s. The roads are described as very narrow and the bridges of logs with no protective rails.

Most of the tourists who came to Grafton over the next forty years came for the hunting and fishing. The fishing was marvelous. In August of 1884 the correspondent noted that Leander Bennett caught forty-three trout in an hour. Leslie Davis remembered that it was not uncommon for his mother to ask him in mid-morning to catch enough fish for dinner. The hunting was also good but at times more difficult. Local men usually got a deer more easily than did the visitors.

Reading these newspaper reports, which cover some forty-five years, bring out certain aspects of Grafton life. Accidents were common. Children cut themselves on scythes -- at times badly -- or stabbed themselves with pitchforks. The men who worked in the woods were always at risk from accidents with saws or axes, falling limbs, or runaway horses. At times these accidents resulted in deaths: today, in the Grafton Cemetery, one can see the marker for a young man lost in the Cambridge River. There were no facilities for local care and no way to get treatment except to harness a horse and head down through the Notch for Bethel.

Illnesses were also common, at times serious and even potentially terrifying. The news of diphtheria or typhoid in one of the lumber camps could send a chill through the community as happened in the 1870s and 1880s, although fortunately there were no epidemics. But pneumonia was well known and always a threat, as was consumption. One gets the impression of a community with a good number of very tough and strong individuals who were able to survive, but where the difficulties of climate and location meant that weaker members were eliminated by disease more quickly than in larger and less remote communities. Almost every family experienced one or more early deaths.

Despite hardships, Grafton citizens met life with courage and energy. They had simple and small pleasures, and they enjoyed each other. There were parties to which everyone was invited and to which almost everyone went. There was dancing and the refreshments were always carefully noted in newspaper reports -- such things as molasses candy, roasted peanuts, lemonade in the summer, berry pies, fudge from a new recipe, etc. There was a Fourth of July picnic for the children and a Christmas tree at the schoolhouse each year. By 1890, the stage brought fresh fish every Friday and at times there were oyster stew parties. The women, under the leadership of Mary Brown Otis, organized a Library, which for years was a source of pleasure and pride; gifts from summer visitors were noted with great satisfaction. Even in the winter they were able to find a source of pleasure in one woman's large collection of house plants or in the handiwork of another's work on quilts. And always there was the thrill of an occasional trip to Bethel or Andover to anticipate and to enjoy. Leslie Davis notes what a treat it was to visit a store twice a year.

By the 1890s the major part of the logging was for soft wood for the Berlin Mills. This cutting was done in the extreme western part of Grafton very near the New Hampshire line. In 1893 the Success Township logging railroad was built from Berlin to the New Hampshire line to take logs directly from Grafton to Berlin. For a number of years this logging was intense. In the first year of using the railroad twenty million board feet of soft wood was taken out. This operation lasted for fourteen years until too much of the accessible (and therefore profitable) wood had been cut. In 1907 this railroad service ceased.

The change in Grafton's fortunes with the cutting of the wood comes through indirectly and gradually in the correspondents' accounts of Grafton doings. More and more items concern Grafton men going to Rangeley or Errol or Milan to log. Increasingly, it is said that only small crews are cutting "this year" in Grafton. It is clear that there was much discussion of other types of work, either actual or anticipated. Men were doing guiding as much as possible. Some were cooking in various establishments, such as Poplar Tavern, rather than in the lumber camps. Others were gathering spruce gum to sell, or going to Gorham, New Hampshire, to see if they could get work. From 1890 on, more and more of the Grafton children who went away to school were staying on to work, coming home only for vacations. The town was dwindling to fewer and fewer homesteads, increasingly inhabited by older people. In 1904, when Leslie Davis was twelve, his family left for Hanover where it was easier to make a living farming. He noted that in the Grafton schools by the late 1890s there were only ten pupils.

In 1910, Mary Brown Otis, who was the first child born in Grafton, died. She was the last of the founding family still living there, for the Browns had prospered but scattered to other Maine towns and cities. Her death brought the sale of the old Brown house which for so many years had housed lumbermen and boarders as well as the family; the Brown Company bought it and used it for storage. Without prospects of real work for the men, Grafton could not survive. In 1919 the Town surrendered its Charter and the remaining farms were sold to the Brown Company except for the Joe Chapman place. Chapman continued to live in Grafton until the 1940s and spent his last year with Leslie Davis.

In the early 1920s the Brown Company razed the remaining buildings in Grafton to lessen the dangers of fire. Today it is hard to find traces, even cellar holes, of the homes that were once there because of years of bulldozing, road construction, timber cutting, and reforesting. Even if its inhabitants had not cut off their wood so prodigally, Grafton could not have survived, for there was no other source of livelihood.

Of the "lost towns" of Oxford County, Grafton is particularly interesting. It was a pioneer community in New England at a time when most Americans think of pioneers only in terms of the settlers streaming west in covered wagons. Despite its remoteness, its smallness, and its lack of many amenities, Grafton was a community of good standards and sound values. Its citizens worked well together and met their problems with courage and resilience. Today, descendants of those Grafton families who left to settle in other Oxford County towns remain justifiably proud of their Grafton origins.

Author's Acknowledgments

The definitive work for the history of the Town of Grafton is Charles B. Fobes' Grafton, Maine: A Human and Geographical Study, published as Bulletin #42 of the University of Maine Studies. Mr. Fobes, a retired Meteorological Aide at the Weather Bureau Office in Portland, is a descendant of Captain James Brown, who founded Grafton in the 1830s. Mr. Fobes also furnished to the Bethel Historical Society an article by a "Special Correspondent" in the Rumford Falls Times of August 26, 1899, which contains interesting information about some of the early settlers and early Grafton. I have used Mr. Fobes' work extensively, and he deserves our gratitude as the rescuer of Grafton's history from oblivion.

I have also used two sources brought to my attention by Randall Bennett, namely Logging Railroads of the White Mountains by C. Francis Belcher, published by the Appalachian Mountain Club (Boston, 1980) and a portion of Charles A. J. Farrar's Illustrated Guidebook to Rangeley, Richardson, Kennebago, Umbagog and Parmachenee Lakes, published in Boston in 1879. Of considerable interest were the memoirs of Leslie Davis in the possession of the Bethel Historical Society.

I was helped considerably by conversations with Beatrice Brooks Brown (granddaughter of the family which ran the Grafton Post Office for many years), Ernest Angevine, Roger Hanscom (who worked for years on the road through the Notch), and Phyllis Davis Dock (who remembered Joe Chapman). Of basic use were the contributions from Grafton correspondents to the Oxford County Advertiser and the Oxford Democrat over the years (often very intermittent) from 1861 on, increasing in regularity by the end of the century. This material was transcribed and made available to me by Agnes Haines. For these sources and assistance I express my thanks.