The Paper-Making Era: Power and Pollution

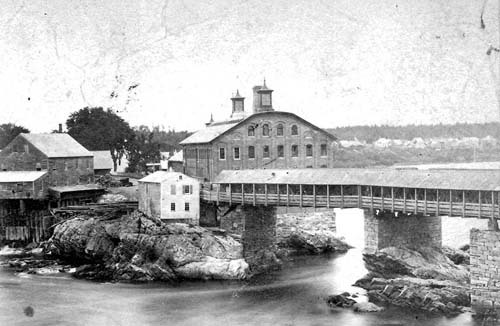

The development of paper manufacturing on the Androscoggin, and the earliest contamination of the river caused by that type of industry, occurred at the Topsham-Brunswick end of the river only a short time after the Civil War. There, in 1868, the Pejepscot Paper Company was established in an imposing Italianate brick structure built high atop a granite ledge on the Topsham side, just below the bridge connecting the two towns. Speaking of this period in the history of the valley, Page Helm Jones wrote the following in his 1975 work, Evolution of a Valley: The Androscoggin Story:

In 1870 the manufacture of paper was done almost entirely with rags, with some admixture of straw and mechanically ground wood. . . . The industry was seeking improvements in pulp, particularly the desired uniformity and possible lower cost which was improbable with rags. By 1881, a few groundwood plants had been started in the East, and in that year the first one was built by the Umbagog Paper Company at Livermore Falls . . . of which Hugh J. Chisholm of Portland was the moving spirit. This man was to become, with W. W. Brown [of Berlin], the second of the two most influential figures in the economic development of the Upper Androscoggin Valley. . . . This was not only the beginning of a new era in the economy of the valley, but the start of serious industrial river pollution which increased yearly for half a century before public outcry against its continual worsening caused . . . action for the recovery of the river to its former usefulness as a thing of beauty and utility, rather than the vile, lifeless, stinking sewer which it became in the 1940s. Unfortunately, the sulfite process of pulping, which was a godsend to the paper industry, created useless waste liquors laden with oxygen-devouring chemicals and insoluble sediment which gradually covered the river bottom, destroying the water vegetation which is so necessary to water life and to the natural ‘self purification’ which the mill operators said would take care of their sewage.

Power to Spare

If the mean volume of water that can, in the present state of its reservoirs, be commanded on the river, in the low run of summer, from Rumford falls to the tide, be assumed to be 75,000 cubic feet per minute, for eleven hours a day, the total power of this section of the river is 85,200 horse-power, gross measurement, for the hours specified, or 3,747,600 spindles. What proportion of this power can be economically appropriated, it is not possible now to determine; the proportion is, however, unquestionably unusually large, owing to the favorable conditions of the bottom and banks, and the advantageous character of the falls and rapids with reference to improvement. Not an eighth part of it is now used.

The water-power of this river from the tide to Jay inclusive, is already furnished with excellent railroad communication close at hand, and from Bethel to the State line the Grand Trunk follows the immediate bank of the river. Indeed, no portion of the river below the State line is far removed from railroads. It is navigable to the foot of the lowest falls, for small craft, for about two-thirds the year.

— Walter Wells, The Water-Power of Maine (1869)

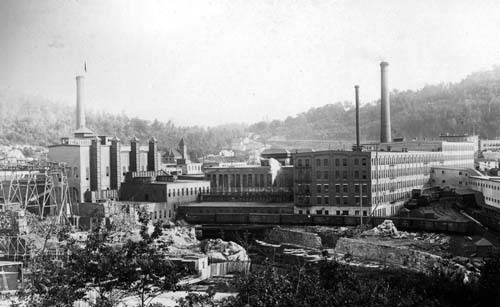

Constructed in 1868 and still standing on the Topsham side of the Androscoggin, the Pejepscot Paper Company is the earliest surviving example in Maine of a wood-pulp mill in the river valley.

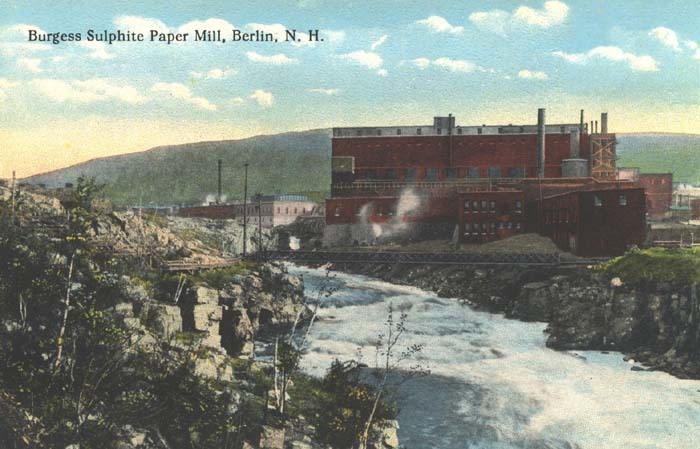

The earliest paper mills at Berlin, New Hampshire, relied on the soda process to making wood pulp—a process that was never completely satisfactory. With the perfection in the mid-1880s of the sulfite process for breaking down wood fibers, this large plant was built on the east side of the Androscoggin River. In a matter of only a few years, the Berlin paper mill (which recently closed) was to become the largest employer in northern New Hampshire.

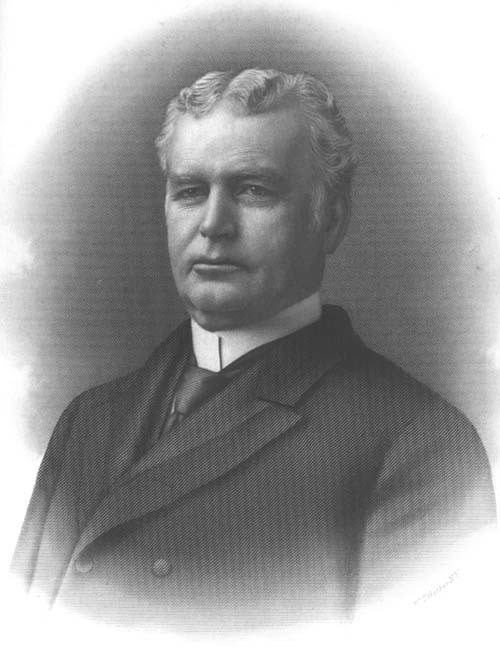

Ambitious and imaginative, Canadian-born industrial giant Hugh J. Chisholm moved to Portland in the 1870s, where he established a successful publishing business. Fascinated by the undeveloped areas of the Androscoggin valley, including those bypassed by railroads, Chisholm organized a paper-manufacturing firm at Livermore Falls in 1881 and another—the Otis Falls Paper Company—in the town of Jay in 1887. Five years earlier, however, he had visited the Great Falls at Rumford and soon became determined to create a “City in the Wilderness” at that location.

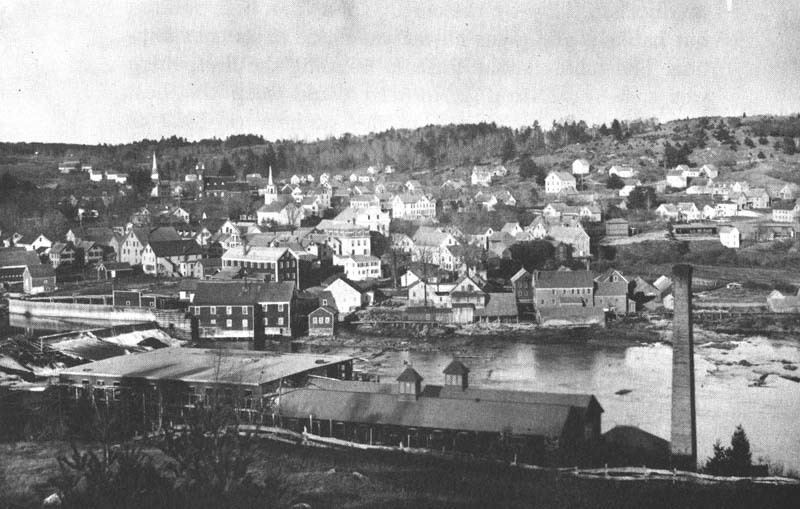

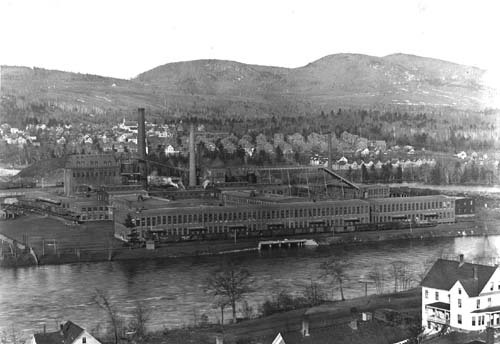

Hugh Chisholm’s Umbagog Paper Mill, in the foreground, was being expanded when this 1885 photo of Livermore Falls was taken. The smaller mills on the opposite side of the Androscoggin included a sawmill, pulp mill, leatherboard mill, gristmill, and a “novelty” (dowel) mill—whose power came from a canal that ran beside and beneath these structures. (With few exceptions, 18th and 19th century mills on the Androscoggin were powered by water channeled through canals that paralleled the main river—an arrangement that helped prevent the structures from being washed away during spring floods.)

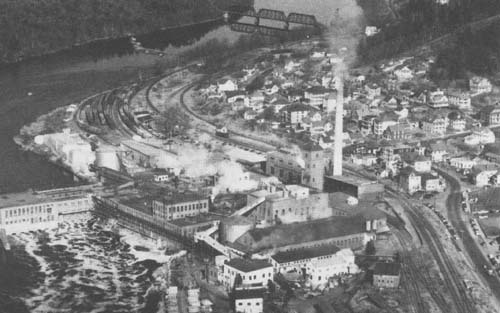

A view of the Otis Falls Paper Company in Jay, Maine, after it became part of Hugh Chisholm’s larger International Paper Company conglomerate. On the left a power plant captures energy from the Androscoggin, while at the right is the village of "Chisholm."

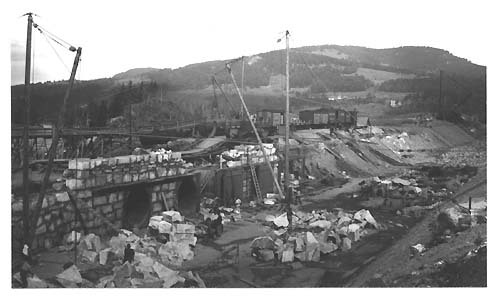

The construction of canals to furnish Androscoggin water to the several mills at Rumford Falls was of paramount importance in the early 1890s. Hugh Chisholm also purchased controlling stock in the Rumford Falls and Buckfield Railway Company, which had reached only as far as Canton in the 1880s—some seventeen miles downriver from Rumford. Chisholm completed the line and eventually connected it to the Grand Trunk and Maine Central railroads.

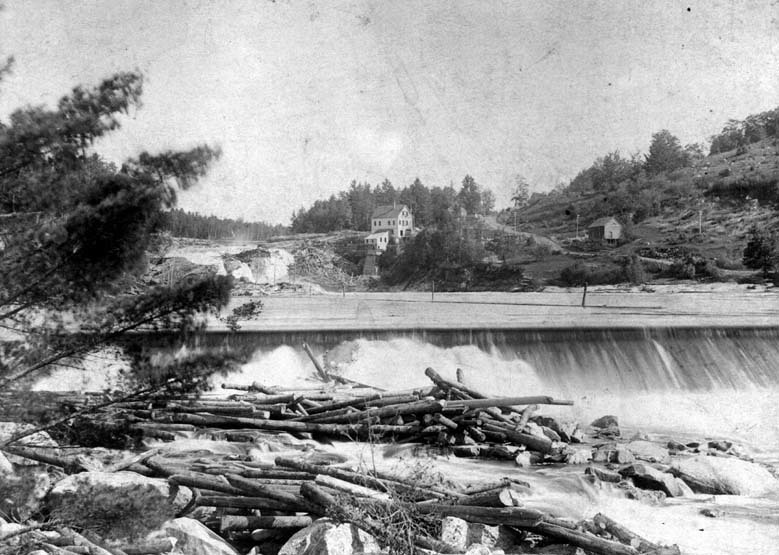

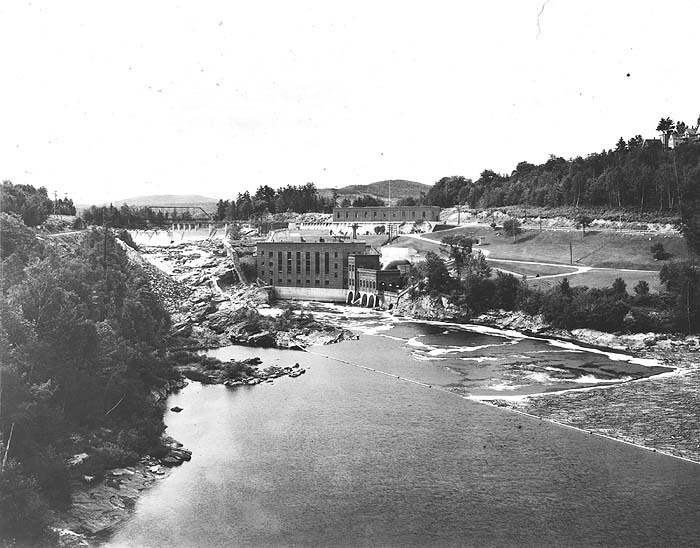

Two views of the Great Falls at Rumford illustrate the dramatic changes that took place there between the 1890s (top photo) and the 1930s (bottom photo) as the cataract was harnessed to produce electricity. During times of drought, most of the river water is channeled through the power station, leaving the falls nearly dry.

The mills of the International Paper Company at Rumford and a broad stone-walled canal are shown in this view dating from about 1910. In the center distance may be seen the power station atop the Great Falls.

Rumford’s Oxford Paper Company, as it looked when paper production started on November 9, 1901. In the foreground is the Androscoggin River, with the “Strathglass Park” housing development on the hillside in the near distance. Some of the chemical and paper wastes entered the river from the granite-lined channel beneath the mill.

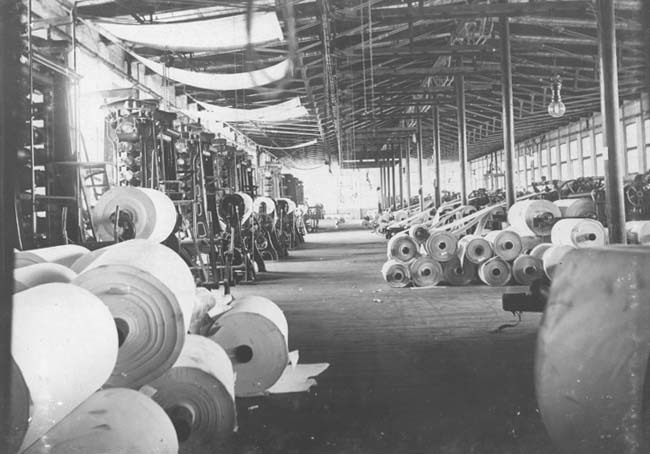

The cutting room at Rumford’s Oxford Paper Company as it appeared around 1910. To reach this stage in papermaking, many unwanted substances from wood were extracted and discharged directly into the Androscoggin. Industrialists, like Hugh Chisholm, mistakenly believed that the river would somehow repurify itself, despite the tremendous tonnage of waste sulfite liquors dumped into it.