Native Americans and the Amascongan

Native Americans lived alongside, and traveled on, the Androscoggin River centuries before the first Europeans explored the coast of Maine, an effort that may have begun as early as the 1490s. Moving up the Androscoggin valley after the glaciers retreated over 12,000 years ago, the ancestors of today’s Abenaki Indians—the “dawn land” people—survived by hunting large game, especially caribou. Termed the “Paleo-Indians” by some scholars, these inhabitants of the valley erected a stone structure for the storage of meat, dated to 11,120 years before the present (and now on display at the Maine State Museum), at the “Vail Site” on the old course of the Magalloway River—a northern tributary to the Androscoggin. Many other prehistoric Indian encampment sites along the Androscoggin, notably on points of land jutting into the river (for example, “Powwow Point” at Bethel) and on raised elevations not far from the water’s edge, have been identified and documented through archaeological investigations carried out by the Maine Historic Preservation Commission and Maine State Museum. Such investigations have aided in the reconstruction of the lifestyles of the original human inhabitants who occupied the Androscoggin watershed.

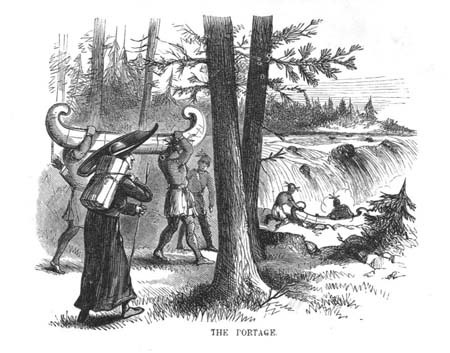

Over a period of many centuries, Native Americans established a system of trails and carrying places ("portages") throughout the Androscoggin watershed. On the subject of trails near the huge waterfalls at Rumford, Dr. William B. Lapham stated in his 1890 History of that town, “It was one of the numerous carrying places on the river, and beaten paths were found along the banks and around the falls by the first English visitors to this region.” A Jesuit priest accompanies his native allies in this view.

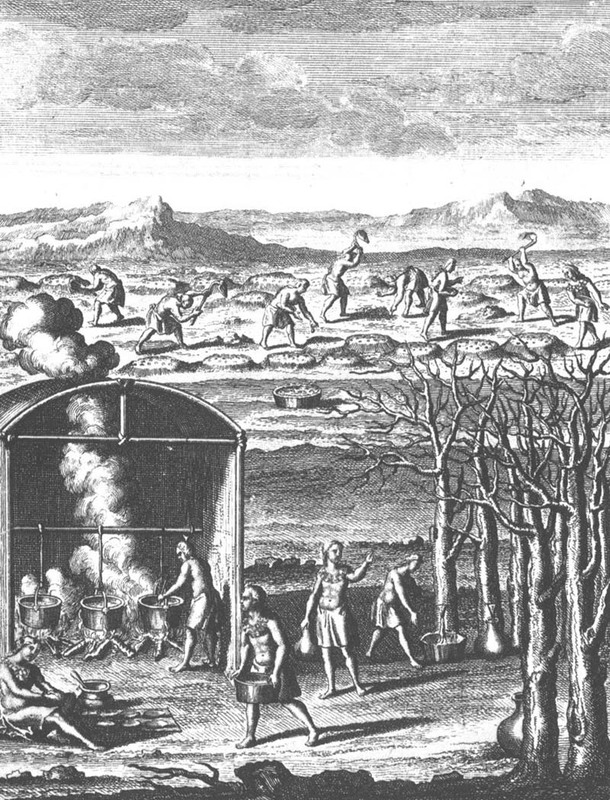

Well before the time of first contact with Europeans, the Abenaki of the Androscoggin valley had developed a culture heavily dependent on agriculture, and at "Rockamecook" (Canton Point), some five hundred acres of corn grown on the Androscoggin intervales were harvested annually. In this engraving dating from the 1580s, northeastern American Indians are shown boiling sap to make syrup, as well as harrowing hills where corn had been planted.

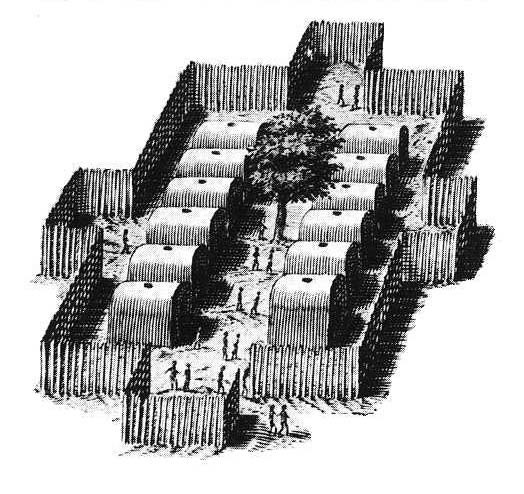

This early 17th century representation of an East Coast Algonquian village conveys an accurate picture of the type of fortified encampments that once dotted the Androscoggin River valley. In 1703, an English scouting party traveling through this region stated: "When we came to the fort, we found about an acre of ground, taken in [palisaded] with timber set in the ground . . . with ports [gates].” At Canton Point, about halfway between the headwaters and mouth of the Androscoggin, a large Abenaki fort with chapel supplied with a French priest, existed well into the 17th century. Other Indian villages within the watershed (and occupied—along with smaller campsites—on a seasonal basis) existed at Bethel, Auburn (Laurel Hill), Lisbon (Pejepscot), Minot, and Sabattus. From Willem Janszoon Baeu’s map, Nova Belgica et Anglia Nova, published in Amsterdam in 1635.

Before dams were constructed by white settlers, the Androscoggin teemed with fish, including thousands of Atlantic salmon that battled their way up the river and its tributaries each spring to spawn. The cold, clear waters of the river were also the year-round home to brook trout, while alewives and shad swam partway up the river each year. Aware of this abundance, the Abenaki sited fishing camps near the base of falls where fish collected as they made their way upstream. Native Americans also trapped beaver and otter on the river.

Throughout ancient times, the Androscoggin was a “great water road” to the Abenaki, both in summer and winter. During the colder months, the smooth ice on the river made travel up and down the valley much easier than over well-worn trails alongside the waterway. Records exist suggesting some white settlers also waited until the river and its feeder streams froze over before making their way to new homes in the upper reaches of the Androscoggin valley.