Molly Ockett and the "Last Indian Raid"

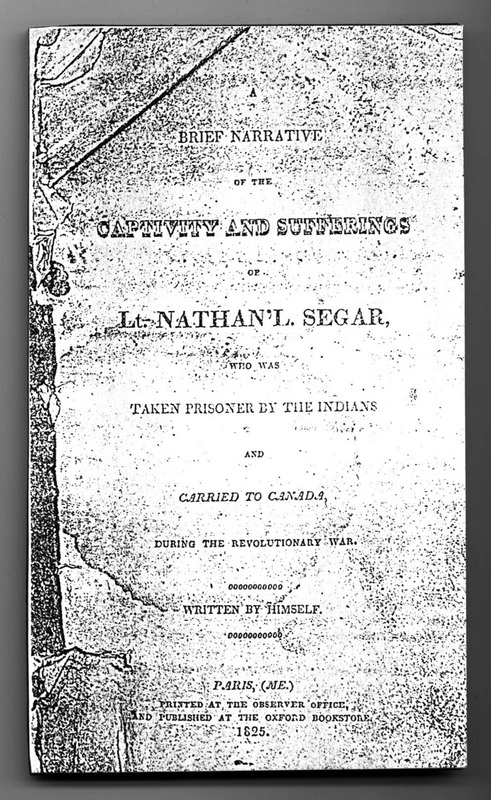

Perhaps the most gripping event to occur in the Bethel region during the American Revolution was the "Last Indian Raid in New England," which took place in the upper Androscoggin River valley on August 2 and 3, 1781. Led by "king" Tumkin Hagen, who had long resented white settlement in the area, a small band of Indians "painted and armed with guns, tomahawks and scalping knives" plundered several houses in Newry, Bethel, and Gilead, Maine, capturing three men and killing a fourth in the latter township. Crossing into New Hampshire, the attackers then raided several cabins in Shelburne, seizing an African-American man named Plato and killing Peter Poor, an early settler. The Indians, with their captives, soon departed for Canada, leaving the remaining inhabitants of Shelburne to spend a restless night atop a local prominence still known as "Hark Hill." Soon thereafter, a militia of thirty Fryeburg men, led by Molly Ockett's ex-partner Sabattis, made a futile attempt to pursue Tumkin Hagen's group and rescue the prisoners. Among the latter was Lt. Nathaniel Segar of Bethel, whose "captivity narrative" published in 1825 highlights the tentative nature of Anglo-Indian relations previous to the 1783 Treaty of Paris that officially ended the Revolutionary War.

Molly Ockett's connection with the 1781 Raid involves an incident reported to have occurred either before or just after the main skirmish. When she learned of Tumkin Hagen's plan, she is said to have rushed several miles through the woods to the camp of Colonel Clark of Boston to tell him that he, too, was to be killed. This magnanimous act, which again demonstrates Molly Ockett's aversion to violence between her fellow natives and their white neighbors, is recounted in Benjamin G. Willey's Incidents in White Mountain History, published in 1856. It is important to note, however, that this account first appeared 40 years after Molly Ockett's death and 75 years after the alleged incident occured. In addition, the identity, and even existence of "Colonel Clark of Boston" has never been satisfactorily determined. (He should not be confused with Jonathan Clark of Bethel, whose involvement in the Indian Raid is well-documented). For these reasons, this story should be read as indicitave of how Molly Ockett was remembered, but not as verified fact:

During the last years of the American Revolution, the northern Indians seem to have determined to make a final struggle for their hunting-grounds and home. . . . No general battle was fought, but after committing many murders and barbarities on the settlers, and greatly annoying them, they retired, forgetting their revenge in the sad and weak condition of their tribe. One Tom Hegan . . . was particularly active in waylaying and killing the whites. He figures conspicuously in all the cruel Indian stories of this region. Sometimes in the employ of the British, and sometimes impelled onward by his own deep hatred, he was very bold, and bloody, and barbarous, and for a long time a terror to the settlers.

A Col. Clark, of Boston, had been in the habit of visiting annually the White Mountains, and trading for furs. He had thus become acquainted with all the settlers and many of the Indians. He was much esteemed for his honesty, and his visits were looked forward to with much interest. Tom Hegan had formed the design of killing him, and, contrary to his usual shrewdness, had disclosed his plans to some of his companions. One of them, in a drunken spree, told the secret to Molly Ockett, a squaw who had been converted to Christianity, and was much loved and respected by the whites. She determined to save Clark's life. To do it, she must traverse a wilderness of many miles to his camp. But nothing daunted the courageous and faithful woman. Setting out early in the evening of the intended massacre, she reached Clark's camp just in season for him to escape. Tom Hegan had already killed two of Clark's companions, encamped a mile or two from him. He made good his escape, with his noble preserver, to the settlements. Col. Clark's gratitude knew no bounds. In every way he sought to reward the kind squaw for the noble act she had performed. For a long time she resisted all his attempts to repay her, until at last, overcome by his earnest entreaties and the difficulty of sustaining herself in her old age, she became an inmate of his family, in Boston. For a year she bore, with a martyr's endurance, the restraints of civilized life; but at length she could do it no longer. She must die, she said, in the great forest, amid the trees, the companions of her youth. Devotedly pious, she sighed for the woods, where, under the clear blue sky, she might pray to God as she had when first converted. Clark saw her distress, and built her a wigwam on the Falls of the Pennacook [Rumford Falls], and there supported her [and] often did he visit her, bringing the necessary provision for her sustenance.

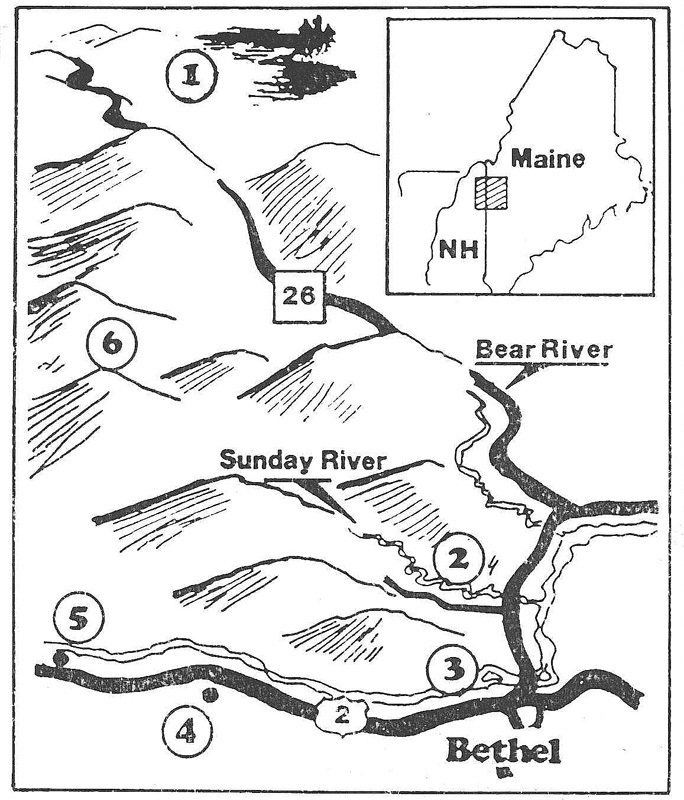

This map pinpoints sites connected with New England's Last Indian Raid of August 2-3, 1781: (1) Indians venture south from Umbagog Lake; (2) Barker homestead on Sunday River attacked; (3) Captives taken at Clark house in Bethel; (4) Gilead settler killed and scalped; (5) Shelburne settler killed and another captured; (6) Indians and captives flee over Mahoosuc Mountains to Canada. Tumkin Hagen, leader of the raiding party, also intended to kill Colonel Clark, camped in the vicinity, but Molly Ockett warned the Boston man in time to save his life.

One of the most interesting documents relating to Anglo-Indian relations during the Revolutionary War is the "captivity narrative" of the early Bethel settler Nathaniel Segar, published in 1825. It was at the time of the Last Indian Raid in New England that Molly Ockett reportedly saved the life of Colonel Clark of Boston.

In August 1931, the people of Bethel celebrated the 150th anniversary of New England's Last Indian Raid with a parade, speeches, a special edition of the local paper, and a "pageant" meant to recreate that long-ago skirmish. The grand climax of this spectacle was the burning of a settlers cabin—a highly dramatic event that did not take place during the actual 1781 Raid.

Around 1800-1805, Molly Ockett is said to have resided for a year in Boston with the family of a Colonel Clark, whose life she reportedly had saved in 1781. Though she probably had visited the city in her youth, Molly Ockett yearned for the North Country and was thankful to return to her familiar haunts in the Androscoggin valley.

Grateful to Molly Ockett for saving his life and aware of her unhappiness living in Boston, Colonel Clark is said to have built her a wigwam near the "Great Falls" at Rumford, some twenty miles downriver from Bethel. This tremendous cataract, shown here in a late 19th century photo originally published in William B. Lapham's History of Rumford, Oxford County, Maine (1890), may have had symbolic meaning to Molly Ockett and others in her kin-group, who regarded themselves as "original proprietors" of the lands upriver of the Great Falls.