Molly Ockett Meets Henry Tufts

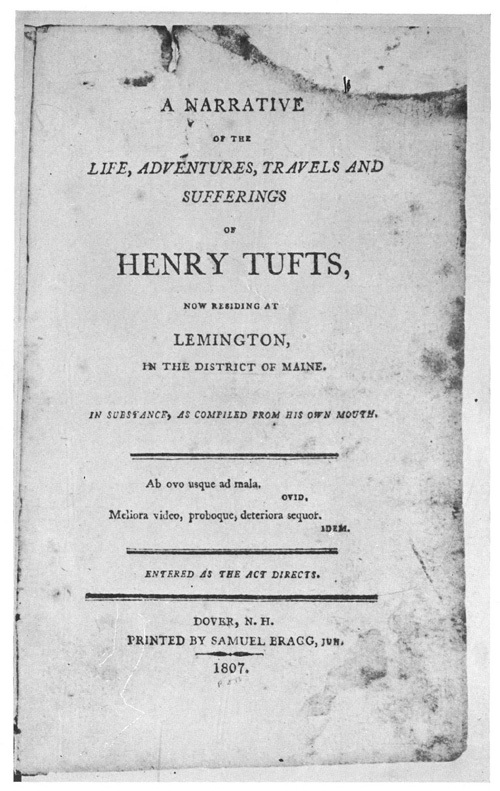

One of the earliest and most detailed accounts of Molly Ockett's life comes from a book about Henry Tufts (1748-1831), a shady character who lived among the Abenaki of western Maine between the spring of 1772 and the spring of 1775, a three-year period during which he learned the Indian language, their medical practices, and their customs. In and out of jail during much of his life, Tufts was, at various times, a counterfeiter, an army deserter, a thief, a bigamist, a doctor, and a preacher. His main reason for visiting the Indians was to find a cure for a serious knife wound he had received in an accident, and fortunate he was that Molly Ockett was there and willing to administer aid. First published in 1807 as A Narrative of the Life, Adventures, Travels, and Sufferings of Henry Tufts, this account provides a rare and intimate glimpse into the private world of an Indian healer during the late 18th century. A new edition of Tufts' book, re-titled The Autobiography of a Criminal, was issued in 1930, and several excerpts from that volume appear below. Tufts died at Limington, Maine, in 1831, "in the eighty-third year of an uncommonly misspent life."

After many and repeated efforts, I reached the Pigwacket country [Fryeburg, Maine, vicinity], where I suspended my travels a few days, to recruit, in some degree, my exhausted strength and spirits. . . . But now I was frequently put to my trumps to trace the most direct course toward the Indian encampments, which, as yet, were thirty miles distant. . . . No long time supervened, ere ascending a great hill, I had a view, for the first time, of their camps and wigwams in Sudbury Canada [Bethel]. . . .

On my approach, their chief, whose name was Swanson, gave me a very cordial reception, and presently ordered his domestics to prepare dinner. . . . I acquainted him with my circumstances, and the design I had formed of residing in [Sudbury] Canada for a season. He seemed pleased with my intentions, and gave me free toleration to abide in his tribe during pleasure. To these instances of benignity he superadded another, which was to enjoin Molly Occut, at that time the great Indian doctress, to superintend the recovery of my health. . . .

. . . I made direct application to the lady for such medicines as might be suitable to my complaints. She was alert in her devoirs, and supplied me for present consumption, with a large variety of roots, herbs, barks and other materials. I did not much like even the looks of them; for to have contemplated an encounter with the formidable forage might have staggered the resolution, doubtless, of a much greater hero than myself. However, I took the budget with particular directions for the use of each ingredient.

My kind doctress visited me daily, bringing new medicinal supplies, but my palate was far from being gratified with some of her doses, in fact they but ill accorded with the gust of an Englishman. Nevertheless having much faith in the skill of my physician, I continued to swallow with becoming submission, every potion she prescribed. Her means had a timely and beneficial effect, since, from the use of them, I gathered strength so rapidly, that in two months, I could visit about with comfort.— The Autobiography of a Criminal; Chapter VII, Life with the Indians, pp. 59-64

Returning health inspired my breast with new-born hope, and was a source of lasting consolation. And now curiosity prompting me to visit the Indian settlements in this department . . . I followed the daily practice of traveling from place to place, until I had visited the whole encampment, and . . . found there might be about three hundred inhabitants in this quarter. The entire tribe, of which these people made a part, was in number about seven hundred of both sexes, and extended their settlements, in a scattering, desultory manner, from lake Memphremagog to lake Umbagog, covering an extent of some eighty miles. . . . I continued the salutary exercise . . . until my health was restored in as full and perfect a manner, as I had possessed that blessing at any former period. This happy restoration to pristine ability I attributed principally to the good offices of my doctoress, who during my convalescence, was indefatigable in her care and attention. Her character was, indeed, that of a kind and charitable woman. . . .

Since beginning to amend in health under the auspices of madam Molly, I had formed a design of studying the Indian practice of physic, though my intention had hitherto remained a profound secret. Indeed I had paid strict attention to everything of a medical nature [and] frequently was I inquisitive with Molly Occut, old Philips, Sabattus and other professed doctors to learn the names and virtues of their medicines. In general they were explicit in communication, still I thought them in possession of secrets they cared not to reveal.

. . . As divers English people used occasionally to visit us to purchase furs and the like, I disposed of my share to those visitants; and among other articles procured ten gallons of rum, with which I regaled a number of my Indian friends, as long as it lasted. By this exploit I so far engaged their good will and gratitude, that no sooner did I acquaint them with my desire to learn the healing art, than they promised me every instruction in their power. . . .

— The Autobiography of a Criminal; Chapter VII, Life with the Indians, pp. 64-68

It had long been an approved custom, among the savages of Sudbury [Canada], to visit Québec, every spring of the year. . . . The principal motives of such journeys were the purchase of absolution of sin, and to have the souls of deceased friends prayed out of purgatory. . . . About the beginning of May, this year, a considerable party, laden with furs, as customary, set out for Québec, but now Molly Occut herself made one of the itinerants. Her motives, in undertaking so troublesome an expedition, were the pardon of her own sins, and the strong desire she had that the soul of her deceased husband should be prayed out of purgatory. He had been dead several years, and she had hitherto neglected to discharge this pious duty. Resolving to atone now for former remissness, she set out . . . with the rest of the company, and with a valuable pack of furs at her back. After the absence of two weeks they returned, bringing home divers articles, which they had in exchange for their furs. On arrival, several of the adventurers recounted . . . a pretty ludicrous anecdote of the worthy doctoress. It related to a transaction that took place between her and a certain Catholic priest, at the time of his praying her husband out of purgatory. . .

Molly having disposed of her furs for cash, about forty dollars . . . went directly to a priest, and acquainted him with her wishes, requesting to know the sum he should ask for performing the godly services. The crafty priest, knowing the sum she had recently received, demanded the whole forty dollars, and insisted on the money being told down, previous to his entrance on the sacred duties. With this unreasonable request she complied . . . and then the treacherous old Levite, with much pretended sanctity, began the solemn farce. In the first instance he gave her pardon and absolution, and next undertook to petition for the departed soul of her late husband. At length . . . he informed her that the business was happily completed, and that her husband's soul was safely delivered from the bonds of purgatory. She, however, was very particular in her inquiries, whether he were certainly clear or not. The old priest asseverated repeatedly that he was absolutely free. On this she scraped the money off the table into the corner of her blanket, and tying it up was about to depart. The priest some nettled, demanded the meaning of her maneuver, and threatened to remand her husband back to purgatory, unless she gave him the money. Her reply was that she knew her husband too well to believe it in a priest's power to do that, for (added she) my husband was always a very prudent man. I have often observed, when we used to traverse the woods together, if he chanced to fall into a bad place, he always stuck up a stake, that he might never be caught there any more. Without further ado, she made the best of her way off, leaving the poor ecclesiastic to console himself for the loss of the money in the best manner he could.

. . . When Molly had returned from Québec . . . I renewed my intense application to medicinal inquiries; generally attending my patroness, when she visited her patients, gaining, by those means, a much better insight into the Indian methods of cure than had otherwise been possible.

— The Autobiography of a Criminal; Chapter VIII, The Daughter of King Tumkin, pp. 78-81