Birth and Early Life

Certain experiences during Molly Ockett's childhood and young womanhood provided a firm foundation for her future role as a bridge between the worlds of the Abenaki and the white settlers. Although born around 1740 at Saco, Maine, Molly Ockett doubtless spent her earliest years sixty miles upriver at Fryeburg, where, according to the historian Dr. Nathaniel T. True, "she was wont to say that she could remember when the pine trees on the plains . . . were not taller than herself." During King George's War (1744-1748), she and other Pigwackets gambled on a political alliance with the British and removed to a coastal location in Plymouth County, Massachusetts, where Molly Ockett no doubt learned to speak English and became acquainted with Protestantism—giving her an advantage over her fellow tribespeople, most of whom knew only Catholic religious rituals and spoke some French but no English.

Between 1750 and 1755, when the so-called "French and Indian War" erupted, Molly Ockett and her kin-group returned to their seasonal movements, apparently living for extended periods at Narankamigouak ("Rockomeka" to English ears), a fortified Abenaki village on the Androscoggin River at Canton Point, some forty miles downriver from Bethel. Situated a relatively safe distance from English settlements, this former mission village was only a two-day portage from the Indian community at Norridgewock, where the nearest Jesuit priest then resided. After the outbreak of the French and Indian War, English authorities initiated a campaign to rid northern New England of the Abenaki once and for all. Utilizing methods that today would be characterized as "ethnic cleansing," the English increased the bounty on Indian scalps to as much as three hundred pounds each and sent troops upriver to destroy individuals and encampments, regardless of their position toward the English. Facing such odds, Molly Ockett's remnant band joined the Abenaki exodus to Canada, where they gathered with others at the St. Francis mission of Odanak in Québec.

The 1759 fall of Québec and the burning of Odanak that same year by Major Robert Rogers and his Rangers signaled a turning point in Molly Ockett's life. Nearly twenty years old at the time, Molly Ockett was at Odanak during that horrific event and barely escaped by hiding behind a bush. With the 1763 Treaty of Paris, the French were effectively eliminated as a political force in Canada, thus allowing the growing English colonial population to the south to spread inland, unfettered by threats from the north or the relatively small number of Abenaki remaining in the region. Their numbers depleted by war and pestilence, the surviving Indians cautiously returned to something resembling their old seasonal patterns of travel, albeit without the support of their former allies in French Canada. For those, like Molly Ockett, who chose to return to their ancestral homelands, a very different world awaited them.

"Marie Agathe" Becomes "Molly Ockett"

The 18th century intermingling of Indian and white cultures is well-illustrated in the matter of Indian names, a later problem for scholars searching for references to Molly Ockett in records made during her lifetime. Many Abenaki Indians in this region were Catholic and received Christian names at baptism from French Catholic missionaries. These names were used by the Indians in communicating with the English and were written phonetically from the Indian pronunciation, emerging in a new form. In some instances, given names were assumed to be surnames, compounding the confusion. Thus Marie Agathe, which sounded with French pronunciation like "Mari Agat," became "Mali Agit" when spoken by the Abenaki, who had difficulty coping with the "r" sound. To English ears, Mali Agit sounded like "Molly Ockett," resulting in the name so thoroughly familiar to residents of this region today. Among the names and spellings used over the years for this individual are the following: Marie Agathe, Mari Agat, Mareagit, Mali Agit, Molly Ockett, Mollyocket, Mollyockett, Molly Occut, Mollocket, Mollockett, Molly Lockett, Moll Lockett, Molly Orcutt, Moll Ockett, Molley Ockett, and Mollywocket.

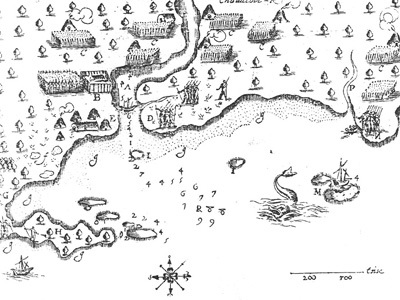

Like other Native Americans inhabiting northern New England, the Pigwackets were a semi-nomadic people, moving easily up and down river in light birchbark canoes in pursuit of sustenance. This 1613 map of Saco, Maine, by Samuel de Champlain includes Abenaki wigwams, longhouses, and cornfields used by the Pigwackets each spring when they left their winter hunting districts near Fryeburg to gather shellfish and other foods on the Atlantic shore. By her own account, Molly Ockett was born around 1740 on a point of land below the falls at Saco during one of these coastal sojourns.

During King George's War, a handful of Pigwacket men volunteered to fight for the English in exchange for protection for their families. In June of 1744, the Pigwacket chieftains Saquant and Weranmanhead (one of whom may have been Molly Ockett's father), with sixteen women and children—including a girl named "Mareagit"—arrived at Saco Falls. Eventually, these Indian families were taken to Weymouth, Massachusetts, and then to a nearby coastal location in Plymouth County, where they remained, "provided for by order of government" for about four years. Following the cessation of hostilities, the Pigwacket families, except for three unwilling young girls, were returned to Maine to be present at peace treaty negotiations at Falmouth in 1749. Among the three recalcitrant girls was Mareagit, who by now was used to English ways and was no doubt uneasy about leaving the Boston area (an early view of Leyden Street in Plymouth is shown here). Nevertheless, she and the other two girls were brought back to Maine, arriving at Fort Richmond on the Lower Kennebec aboard an English sloop in the spring of 1750.

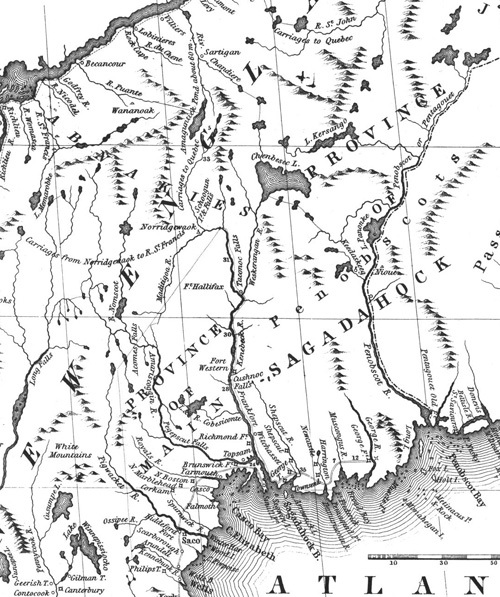

In this detail from John Mitchell's 1755 Map of the British and French Dominions in North America, we have an intimate view of Molly Ockett's world at the outbreak of the so-called French and Indian War (1755-59), when many Abenaki found safe haven at the Canadian mission village of Odanak on the St. Francis River. Note the "Pigwacket R[iver]" at the bottom left, a major focal point in the lives of generations of Molly Ockett's ancestors. This map, used in the peace negotiations ending the American Revolution, identifies numerous English forts and settlements along what is now Maine's southern and central coast.

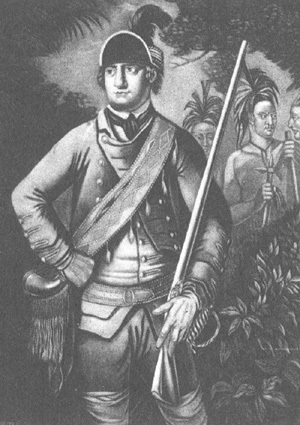

Known to the Abenaki as "the White Devil," Major Robert Rogers of the British Army was ordered to neutralize New France's Native allies in 1759. Showing little mercy, Rogers and his Rangers destroyed Odanak (or "Arasagunticook," as it was then called), the main Abenaki village in the St. Lawrence River Valley, killing many of its residents and burning most of its buildings, including the church. Molly Ockett witnessed the attack by Rogers' men and survived by secreting herself in some bushes nearby.